by N. Gabriel Martin

It seems to make sense to start investigating any question by looking at the facts. However, often the question of what the facts are depends on what we decide is worth talking about.

In a second season episode of Mad Men the star of the show, philandering drunkard Don Draper, is enjoying a rare moment of happiness with his family at a picnic. Saying “We should probably go if we don’t want to hit traffic,” he stands up, chucks his beer away, and walks to the car. His wife, Betty, shakes out the picnic blanket, letting their trash loft into the air before settling on the well-kept lawn.

It is one of the most effective demonstrations of the difference between the show’s era and our own (the season is set in 1962). With the taboo against littering firmly instilled in me, as it is in any North American of my generation, I felt a twinge of disapproval at Don’s can toss, followed by horror at the trash strewn around the park by Betty’s careless flick of the picnic blanket. Betty and Don’s efficient and graceful motions came at my generation’s mores like a one-two punch. Don’s toss put me off balance so that Betty’s flick could deliver the knock-out blow.

The Dapers’ utter nonchalance convey that what they’re doing isn’t out of keeping with what is proper. The Drapers are anything but disorderly. In fact, good manners and hygiene have been the sole topic of the dialogue of the scene: Don tells Betty to check their hands before they get in the car; Betty tells her daughter that it is rude to talk about money. These are people who are hyper-aware of what is acceptable and what is not, but evidently there is nothing unacceptable to them about the most flagrant littering. Read more »

Billions of people around the world continue to live in great poverty. What is the responsibility of rich countries to address this?

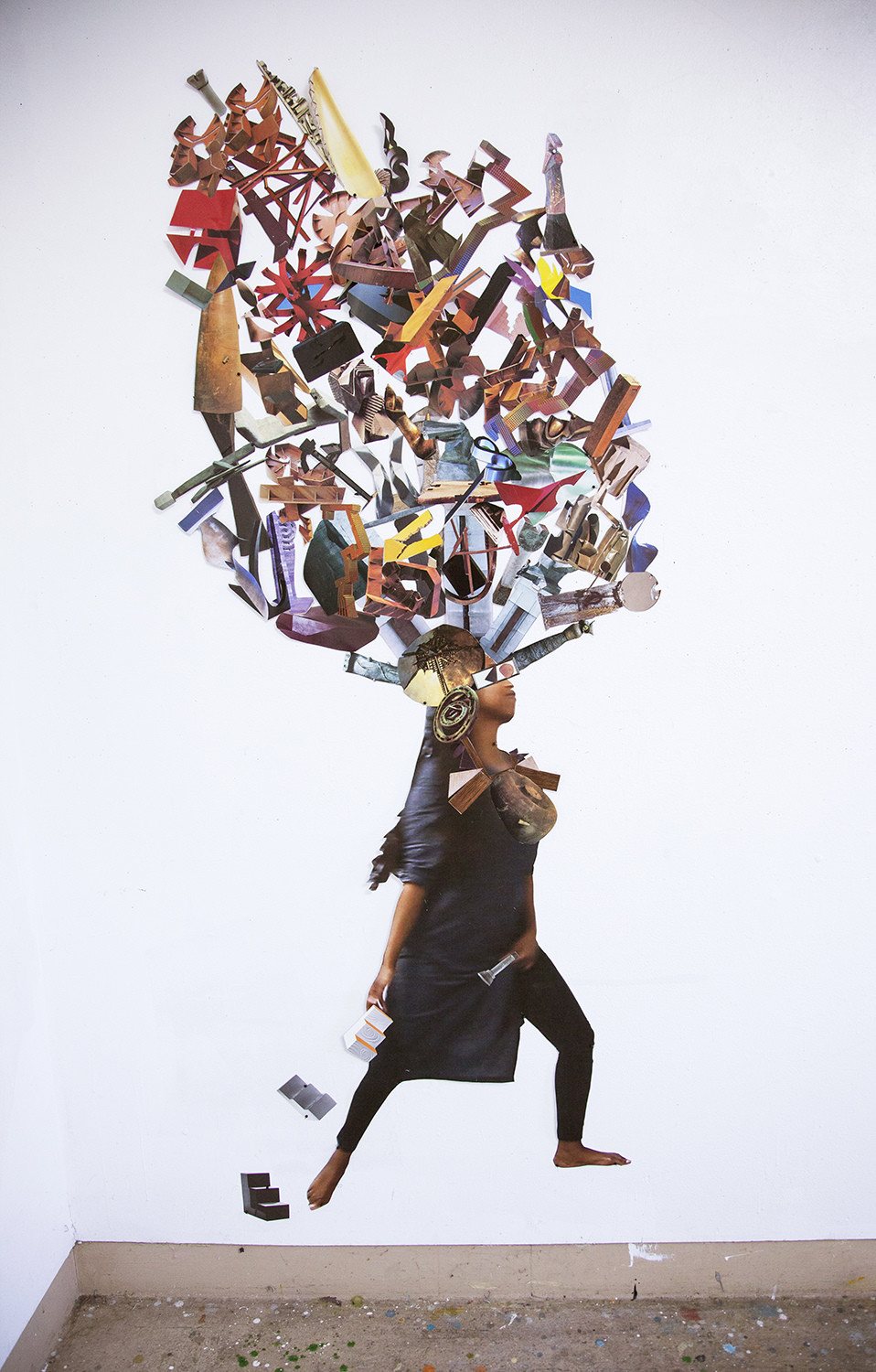

Billions of people around the world continue to live in great poverty. What is the responsibility of rich countries to address this? The best thing about a painting is that no two people ever paint the same one. They could be sitting in the same garden, staring at the same tree in the same light, poking the same brush in the same pigments, but in the end none of that matters. The two hypothetical tree-paintings are going to turn out different, because the two hypothetical painters are different also.

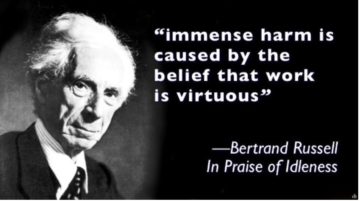

The best thing about a painting is that no two people ever paint the same one. They could be sitting in the same garden, staring at the same tree in the same light, poking the same brush in the same pigments, but in the end none of that matters. The two hypothetical tree-paintings are going to turn out different, because the two hypothetical painters are different also. The work ethic is deeply ingrained in much of modern society, both Eastern and Western, and there are many forces making sure that this remains the case. Parents, teachers, coaches, politicians, employers, and many other shapers of souls or makers of opinion constantly repeat the idea that hard work is the key to success–in any particular endeavour, or in life itself. It would be a brave graduation speaker who seriously urged their young listeners to embrace idleness. (I did once hear Ariana Huffington advise Smith College graduates to “sleep their way to the top,” but she essentially meant that they should avoid burn out by ensuring that they get sufficient rest.)

The work ethic is deeply ingrained in much of modern society, both Eastern and Western, and there are many forces making sure that this remains the case. Parents, teachers, coaches, politicians, employers, and many other shapers of souls or makers of opinion constantly repeat the idea that hard work is the key to success–in any particular endeavour, or in life itself. It would be a brave graduation speaker who seriously urged their young listeners to embrace idleness. (I did once hear Ariana Huffington advise Smith College graduates to “sleep their way to the top,” but she essentially meant that they should avoid burn out by ensuring that they get sufficient rest.)

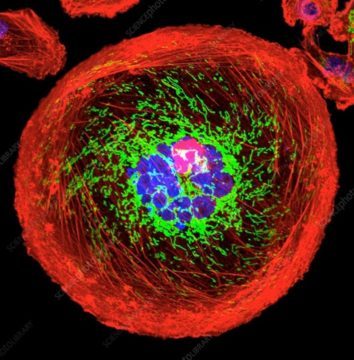

Ninety percent cancers diagnosed at Stage I are cured. Ninety percent diagnosed at Stage IV are not. Early detection saves lives. Unfortunately, more than a third of the patients already have advanced disease at diagnosis. Most die. We can, and must, do better. But why be satisfied with diagnosing Stage I disease that also requires disfiguring and invasive treatments? Why not aim higher and track down the origin of cancer? The First Cell. To do so, cancer must be caught at birth. This remains a challenging problem for researchers.

Ninety percent cancers diagnosed at Stage I are cured. Ninety percent diagnosed at Stage IV are not. Early detection saves lives. Unfortunately, more than a third of the patients already have advanced disease at diagnosis. Most die. We can, and must, do better. But why be satisfied with diagnosing Stage I disease that also requires disfiguring and invasive treatments? Why not aim higher and track down the origin of cancer? The First Cell. To do so, cancer must be caught at birth. This remains a challenging problem for researchers. In the beginning, the god of the

In the beginning, the god of the  In long plane journeys I do not sleep well. But some years back in one such journey I was tired and fell fast asleep. When I woke up, I saw a little note on my lap. It was from the captain in charge of the plane. It said, “I did not want to disturb you, but from our computer log I could see that your total travel so far with our airlines group just crossed 3 million miles. So congratulations! It seems you travel almost as much as I do.” I made a quick calculation, 3 million miles is like 6 return trips from the earth to the moon. With a deep sigh I chanted to myself, as our plane was hurtling through the night sky, a word from an ancient Sanskrit hymn: Charaiveti (keep moving!)

In long plane journeys I do not sleep well. But some years back in one such journey I was tired and fell fast asleep. When I woke up, I saw a little note on my lap. It was from the captain in charge of the plane. It said, “I did not want to disturb you, but from our computer log I could see that your total travel so far with our airlines group just crossed 3 million miles. So congratulations! It seems you travel almost as much as I do.” I made a quick calculation, 3 million miles is like 6 return trips from the earth to the moon. With a deep sigh I chanted to myself, as our plane was hurtling through the night sky, a word from an ancient Sanskrit hymn: Charaiveti (keep moving!)

Blood of the Beasts (Le sang des bêtes)

Blood of the Beasts (Le sang des bêtes)

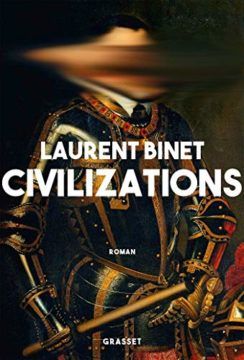

One of my oldest friends, an economic historian who serves as the Academic Director of a museum of Jewish life in northern Germany, is, like me, a child of May; and, during our recent birthday month, as is our custom, we exchanged gifts by post. Since we also share a love of books and history and a taste for grand, occasionally outlandish theory, as well as an abhorrence for futuristic science fiction, the novels we sent each other were in equal measures fantastical and backward-looking: examples of counterfactual historical fiction, what has come to be known as uchronia, the imaginative remaking of a bygone era that is the temporal counterpart to utopian geography.

One of my oldest friends, an economic historian who serves as the Academic Director of a museum of Jewish life in northern Germany, is, like me, a child of May; and, during our recent birthday month, as is our custom, we exchanged gifts by post. Since we also share a love of books and history and a taste for grand, occasionally outlandish theory, as well as an abhorrence for futuristic science fiction, the novels we sent each other were in equal measures fantastical and backward-looking: examples of counterfactual historical fiction, what has come to be known as uchronia, the imaginative remaking of a bygone era that is the temporal counterpart to utopian geography.