by Ethan Seavey

I sit in Parc des Buttes-Chaumont in this the 19th and penultimate arrondissement. We are a pocket of American students lounging down by the perfectly circular pond. We rehash old jokes in unapologetic English which go unheard by the hundreds of Parisians sitting on the hill like Greek citizens watching lesser and stupider gods. It is the weekend so we cross the city on the Métro and by pure luck make it to our destination and once we’ve arrived we mispronounce the name of this handsome park.

Right at the edge of the water stands a man who rips off pieces of bread from the bakery and throws them to the mallards who flock before him. The duck man loves them and they return the feeling. But he so hates the pigeons which walk up to him on the grass and seek the crumbs he throws to the mallards. When they approach he kicks at them; and if they watch from nearby, he chases them with a fallen bough from a horse chestnut tree. He smokes something that is not tobacco and is not cannabis. It smells pleasant enough. It makes him more relaxed and still more vicious towards the approaching pigeons.

We sit by the water and some of us watch him. We are New Yorkers though most of us have only been in New York for a year or two because our time spent studying at Washington Square was cut short by the pandemic. And in New York at Washington Square there is no duck man and there is the pigeon man. We loved to see him enveloped by the purple green flashes of gray feathered flock. He let every oil-slicked feral disfigured city bird onto his lap and onto his shoulder and head. Read more »

Baseera Khan. A New Territory, 2021.

Baseera Khan. A New Territory, 2021. If we take action now to mitigate global climate change, it might make life a little worse for people now and in the near future, but it will make life much better for people further in the future. Suppose, for whatever reason, we do nothing.

If we take action now to mitigate global climate change, it might make life a little worse for people now and in the near future, but it will make life much better for people further in the future. Suppose, for whatever reason, we do nothing.

As a consequential Supreme Court term gets underway, with potentially large consequences for women’s autonomy and health, it’s worth thinking about the ways in which judges do or do not consider the real world consequences of their decisions.

As a consequential Supreme Court term gets underway, with potentially large consequences for women’s autonomy and health, it’s worth thinking about the ways in which judges do or do not consider the real world consequences of their decisions.

I knew that Cambridge was by the river Cam, but the first day when I looked for it I could not find it. From the map I knew that on my way to the Economics Department I had to cross it, I stopped and looked around but I could not see anything like a river. Then I asked a passerby, and he pointed to what I had thought was a small ditch or a canal. It was difficult to take it as a river, as in India I was used to much bigger rivers. Over time, however, I saw the serene beauty of this mini-river, with its placid water by the weeping willows, the swans, gliding boats and all.

I knew that Cambridge was by the river Cam, but the first day when I looked for it I could not find it. From the map I knew that on my way to the Economics Department I had to cross it, I stopped and looked around but I could not see anything like a river. Then I asked a passerby, and he pointed to what I had thought was a small ditch or a canal. It was difficult to take it as a river, as in India I was used to much bigger rivers. Over time, however, I saw the serene beauty of this mini-river, with its placid water by the weeping willows, the swans, gliding boats and all.

The well-known counterintuitive Monty Hall problem continues to baffle people if the emails I receive are any indication. A meta-problem is to understand why so many people are unconvinced by the various solutions. Sometimes people even cite the large number of the unconvinced as proof that the solution is a matter of real controversy, just as in politics an inconvenient fact, such as the ubiquity of Covid-19, is obscured by fake controversies.

The well-known counterintuitive Monty Hall problem continues to baffle people if the emails I receive are any indication. A meta-problem is to understand why so many people are unconvinced by the various solutions. Sometimes people even cite the large number of the unconvinced as proof that the solution is a matter of real controversy, just as in politics an inconvenient fact, such as the ubiquity of Covid-19, is obscured by fake controversies.

It had been a long time since I thought about lawns. I don’t mean in a grand philosophical sense, or the stoned contemplation of a single blade of grass. I mean thought about them at all. Before moving to Mississippi we had lived in Vancouver for 13 years, where we felt lucky to have a place to store our toothbrushes and maybe an extra pair of slacks; we really hit the jackpot when we acquired a postage-stamp-sized balcony on which we could murder tomato plants. Actual yards were out of the question for anyone who hadn’t bought a house on the west end of town 30 years ago; by the time we moved to Vancouver in 2006 as a tenure-track assistant professor and a trailing-spouse adjunct, it was already clear that we would never own a lawn.

It had been a long time since I thought about lawns. I don’t mean in a grand philosophical sense, or the stoned contemplation of a single blade of grass. I mean thought about them at all. Before moving to Mississippi we had lived in Vancouver for 13 years, where we felt lucky to have a place to store our toothbrushes and maybe an extra pair of slacks; we really hit the jackpot when we acquired a postage-stamp-sized balcony on which we could murder tomato plants. Actual yards were out of the question for anyone who hadn’t bought a house on the west end of town 30 years ago; by the time we moved to Vancouver in 2006 as a tenure-track assistant professor and a trailing-spouse adjunct, it was already clear that we would never own a lawn.

Robert Dash. Flower Bud of the Arbequina Olive Tree (black olives).

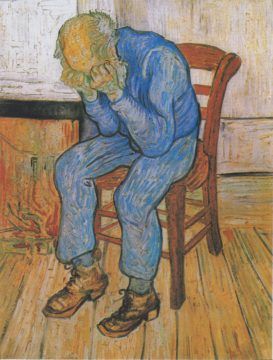

Robert Dash. Flower Bud of the Arbequina Olive Tree (black olives). What is it to be twenty? Forty? Sixty? Eighty? These points that mark the four quarters of a life — fifths if you’re lucky, larger portions if you’re not.

What is it to be twenty? Forty? Sixty? Eighty? These points that mark the four quarters of a life — fifths if you’re lucky, larger portions if you’re not.  1. The public library is holding a book or DVD for me.

1. The public library is holding a book or DVD for me.