by Pranab Bardhan

All of the articles in this series can be found here.

Sachin Chaudhuri, who lived in Bombay, came to know, I think from Binod Chaudhuri, about my teenage forays into writing political pieces, and he asked me to share them with him, and sent back detailed (handwritten) comments on them. A little later he started encouraging me to write for EW (copies of which he sent me every week). But I was too diffident; I was a neophyte Economics student, and I knew of EW’s sky-high reputation (Prime Minister Nehru had a standing instruction to his assistants that as soon as the weekly comes out it should immediately be at his desk). Many years later in my MIT days when I met Paul Samuelson, the great American economist, he once told me that he thought EW was a unique magazine, having topical columns on every week’s events and at the same time publishing specialized analytical articles, some quite technical. I found out that he, like many stalwart economists and other social scientists in the world at that time, had himself written for EW—this was partly a tribute to the magnetic personality of Sachin Chaudhuri which attracted some of the finest minds and created a rich intellectual aura around the magazine.

Sachin Chaudhuri, who lived in Bombay, came to know, I think from Binod Chaudhuri, about my teenage forays into writing political pieces, and he asked me to share them with him, and sent back detailed (handwritten) comments on them. A little later he started encouraging me to write for EW (copies of which he sent me every week). But I was too diffident; I was a neophyte Economics student, and I knew of EW’s sky-high reputation (Prime Minister Nehru had a standing instruction to his assistants that as soon as the weekly comes out it should immediately be at his desk). Many years later in my MIT days when I met Paul Samuelson, the great American economist, he once told me that he thought EW was a unique magazine, having topical columns on every week’s events and at the same time publishing specialized analytical articles, some quite technical. I found out that he, like many stalwart economists and other social scientists in the world at that time, had himself written for EW—this was partly a tribute to the magnetic personality of Sachin Chaudhuri which attracted some of the finest minds and created a rich intellectual aura around the magazine.

Finally I yielded, and my first EW article (it was a review article on a book by the Chicago economist Bert Hoselitz, the founding editor of the journal Economic Development and Cultural Change) came out while I was still at Presidency College. Since then over many decades I have lost count of the number of pieces I have contributed to EW and its successor EPW, some articles on quantitative analysis, some others straightforward opinion pieces. (Every time I have felt like paying a small part of my debt to Sachin Chaudhuri). Read more »

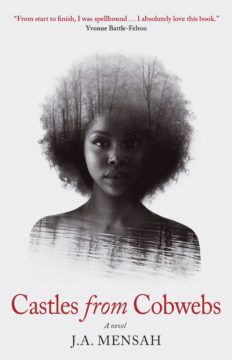

In these dying days of summer, as I steel myself for the onslaught of an uncertain term ahead, I’ve been reading

In these dying days of summer, as I steel myself for the onslaught of an uncertain term ahead, I’ve been reading  The Italian author Sandro Veronesi’s latest novel, his ninth, The Hummingbird, is a clever book that offers the reader both literary pleasure and serious thought. The novel is essentially a family saga, and like all family histories and stories it has a complexity of interpersonal relationships and human emotions all woven into the story. It sounds so typical of life and the reader might begin to think that the novel is a family saga that could be tedious, but that is far from the truth. Veronesi has skilfully used structure to fracture any complacency or perception of the characters and the story, and his novel is a superb piece of skilled writing with unexpected twists and turns.

The Italian author Sandro Veronesi’s latest novel, his ninth, The Hummingbird, is a clever book that offers the reader both literary pleasure and serious thought. The novel is essentially a family saga, and like all family histories and stories it has a complexity of interpersonal relationships and human emotions all woven into the story. It sounds so typical of life and the reader might begin to think that the novel is a family saga that could be tedious, but that is far from the truth. Veronesi has skilfully used structure to fracture any complacency or perception of the characters and the story, and his novel is a superb piece of skilled writing with unexpected twists and turns.

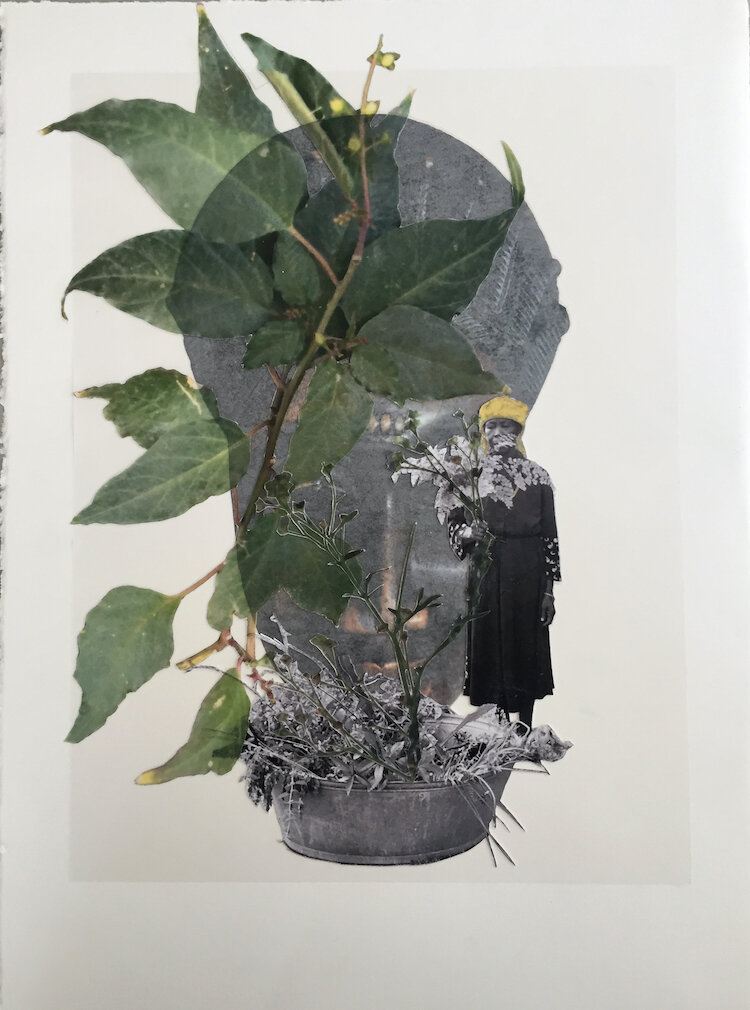

Andrea Chung. From the series Vex, 2020.

Andrea Chung. From the series Vex, 2020.

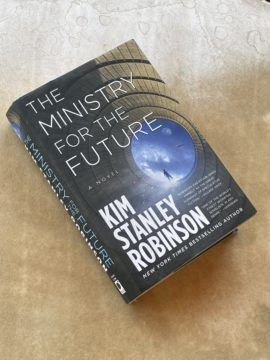

The day I began writing this essay, Portland Oregon braced for yet another round of uncharacteristic heat. Over several months of preparation, as I had been reading and pondering Kim Stanley Robinson’s big, detailed, hyper-realistic science-fiction book The Ministry for the Future, our normally cool northwest town had found itself repeatedly facing drought and high temperatures. Now we were about to be trapped under a “heat dome” of 115 degrees Fahrenheit (46° C) – Las Vegas temperatures, Abu-Dhabi temperatures – for days on end.

The day I began writing this essay, Portland Oregon braced for yet another round of uncharacteristic heat. Over several months of preparation, as I had been reading and pondering Kim Stanley Robinson’s big, detailed, hyper-realistic science-fiction book The Ministry for the Future, our normally cool northwest town had found itself repeatedly facing drought and high temperatures. Now we were about to be trapped under a “heat dome” of 115 degrees Fahrenheit (46° C) – Las Vegas temperatures, Abu-Dhabi temperatures – for days on end.

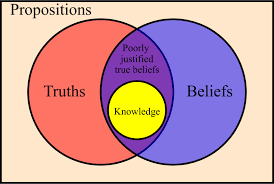

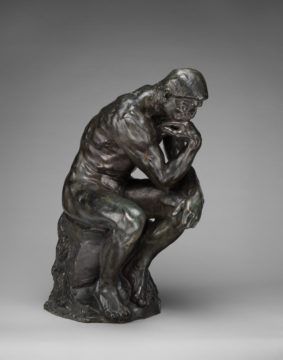

Theories that specify which properties are essential for an object to be a work of art are perilous. The nature of art is a moving target and its social function changes over time. But if we’re trying to capture what art has become over the past 150 years within the art institutions of Europe and the United States, we must make room for the central role of creativity and originality. Objects worthy of the honorific “art” are distinct from objects unsuccessfully aspiring to be art by the degree of creativity or originality on display. (I am understanding “art” as a normative concept here.)

Theories that specify which properties are essential for an object to be a work of art are perilous. The nature of art is a moving target and its social function changes over time. But if we’re trying to capture what art has become over the past 150 years within the art institutions of Europe and the United States, we must make room for the central role of creativity and originality. Objects worthy of the honorific “art” are distinct from objects unsuccessfully aspiring to be art by the degree of creativity or originality on display. (I am understanding “art” as a normative concept here.)

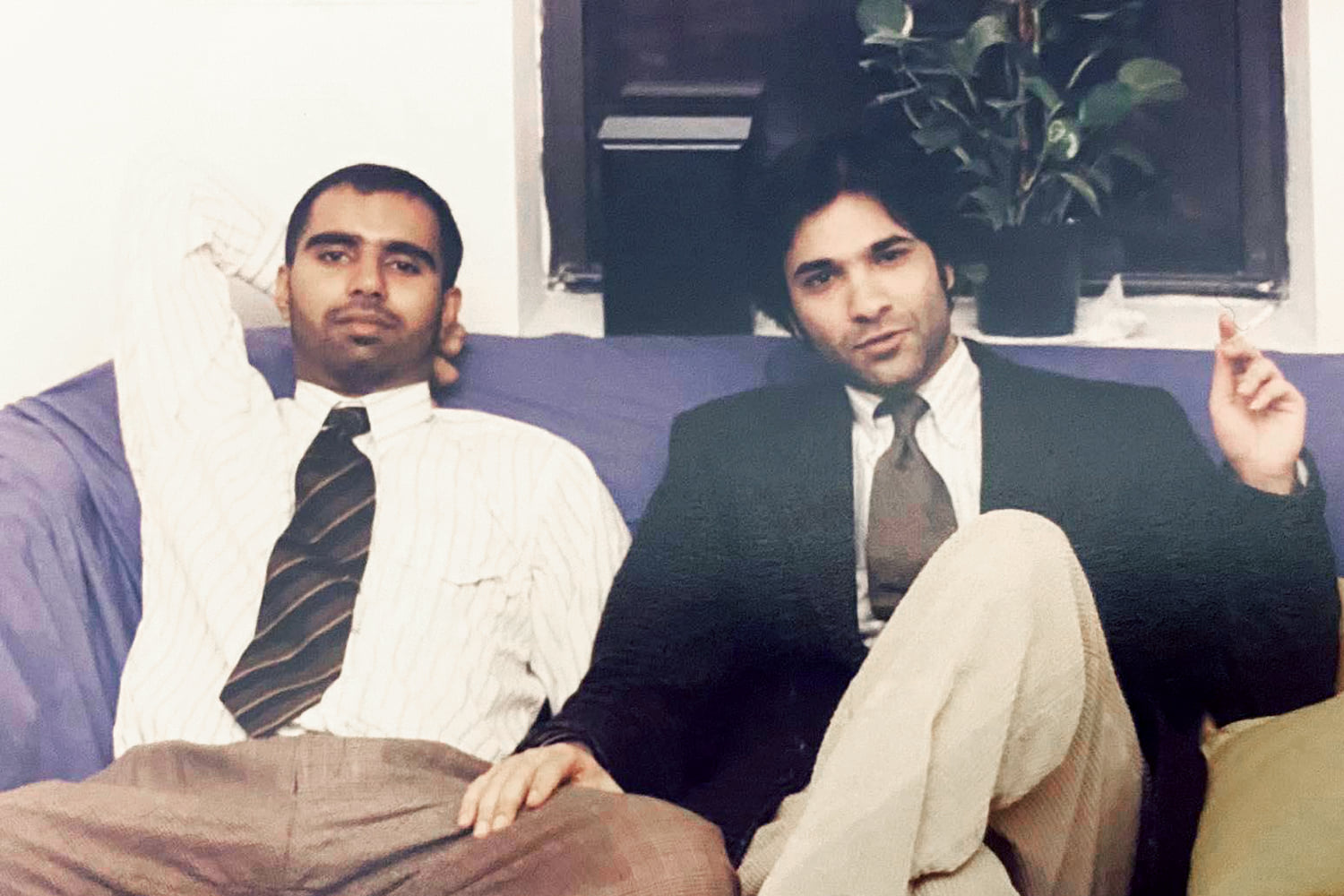

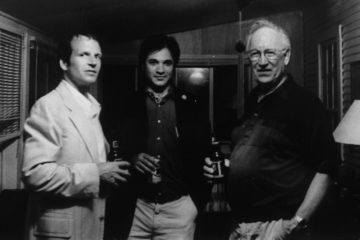

Recently I came upon this photo of my friend Eric, me, and his father, tucked into a book that I was trying to place in the correct place on my shelves as a part of a recent book-organizing effort and it made me think about one of the scarier events in my life. It was 2004. It was also only a couple of years after 9/11 and by then the Patriot Act was in full effect and I personally knew completely innocent people who had been caught up in the “bad Muslim” dragnet and had been detained, deported from America, etc. It was in this atmosphere that I was invited to attend my good friend Eric’s wedding on a lake in Michigan. I found the cheapest ticket possible which would involve a stopover in Pittsburgh on the way to Detroit from NYC and a stop in Philadelphia on the way back. I also reserved a rental car at the Detroit airport to get to the rural lake where the wedding was going to be.

Recently I came upon this photo of my friend Eric, me, and his father, tucked into a book that I was trying to place in the correct place on my shelves as a part of a recent book-organizing effort and it made me think about one of the scarier events in my life. It was 2004. It was also only a couple of years after 9/11 and by then the Patriot Act was in full effect and I personally knew completely innocent people who had been caught up in the “bad Muslim” dragnet and had been detained, deported from America, etc. It was in this atmosphere that I was invited to attend my good friend Eric’s wedding on a lake in Michigan. I found the cheapest ticket possible which would involve a stopover in Pittsburgh on the way to Detroit from NYC and a stop in Philadelphia on the way back. I also reserved a rental car at the Detroit airport to get to the rural lake where the wedding was going to be. Philosophers are prone to define

Philosophers are prone to define  This week I had planned to present the 3 Quarks Daily readership with a fluffy little piece about my memories of a grade school foreign language teacher. It was poignant, it was heartfelt, it was funny (if I do say so myself). Above all, it was intended as a brief respite from the nonstop parade of horrors scrolling past our screens every day—a parade in which my own recent writings have occupied a lavishly decorated float. We all deserve a break, I thought. It would be nice to look at some baton twirlers for a minute, listen to an oompa band.

This week I had planned to present the 3 Quarks Daily readership with a fluffy little piece about my memories of a grade school foreign language teacher. It was poignant, it was heartfelt, it was funny (if I do say so myself). Above all, it was intended as a brief respite from the nonstop parade of horrors scrolling past our screens every day—a parade in which my own recent writings have occupied a lavishly decorated float. We all deserve a break, I thought. It would be nice to look at some baton twirlers for a minute, listen to an oompa band.

Sughra Raza. Karachi Afternoon Sun, 2010.

Sughra Raza. Karachi Afternoon Sun, 2010.