by Leanne Ogasawara

1.

The year is 2025.

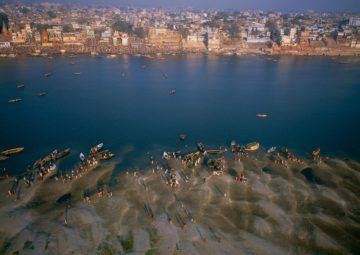

Frank, who is an American aid worker living in northern India, is alarmed to wake up one morning to an outside temperature of 103° F with 35% humidity. Things go from bad to worse, when the power grid goes down, and there is no air conditioning. As temperatures climb to 108° F with 60% humidity, people begin dying. They are being cooked to death.

Known as a wet-bulb temperature event, a sustained combination of high temperature plus high humidity exceeding wet-bulb temperature 35 °C (95 °F) will likely cause death, even in a healthy person sitting in the shade with plenty of water to drink.

When things become unbearable, Frank takes refuge with many others in a shallow lake. But the water is too warm –and by morning, everyone in the lake but Frank is dead. He has no idea why he survived –but life will never be the same.

The shock surrounding the event, which saw millions die in Uttar Pradesh, led to the formation of the Ministry for the Future. Part of the United Nation’s Convention on Climate Change, it was founded under Article 14 of the Paris Agreement with an office set up in Zürich.

The people of India are rightly furious. They point out that the Europeans sucked their resources dry for hundreds of years, and by the time they shook free of their colonialist yoke and tried to develop, they were being told by wealthy Europeans that, “Sorry, you are too late to the party. Rising CO2 and all that.” Indian leadership argues that they use far less coal-generated electricity to bring their people out of poverty than the Americans do to live what in America is considered a normal life.

Located in a part of the world that will bear the initial brunt of the crises, India had expected that other members of the Paris Convention would come to their aid.

Drones were seen overhead so the Indian people knew the situation was being monitored, but at the end of the day, they appeared to be left to die.

And so, they decide to take matters into their own hands.

2.

If one percent of the humans alive controlled everyone’s work and took far more than their share of the benefits of that work, while also blocking the project of equality and sustainability however they could, that project would become more difficult. This would go without saying, except that it needs saying. –KSR

3.

I agree. It does need saying. The coming disasters are not going to affect people equally. In fact, the effects will be felt in inverse relation to the inequality that generated the problems in the first place.

With this in mind, India is worried enough to launch a fleet of airplanes that will disperse sulfur compounds into the atmosphere. Gaining extreme altitude, the pilots release chemicals to try and simulate the dimming effects that follow major volcanic eruptions. Other nations around the world toy with various other “fixes,” like drilling holes at the base of Antarctica and Greenland glaciers to drain runoff water and trying to dye melted arctic waters yellow so it stops absorbing so much solar radiation.

Frank, who is suffering from severe post-traumatic stress disorder wants to become part of a real solution not another fix—even if that means terrorism and killing.

What is so startling about this novel is that it kicks off in 2025. Just four years into the future!

I think if we have learned nothing else in 2020, it’s that things can change very quickly indeed. And that is where the Ministry of the Future is most brilliant, for the future is just four years away.

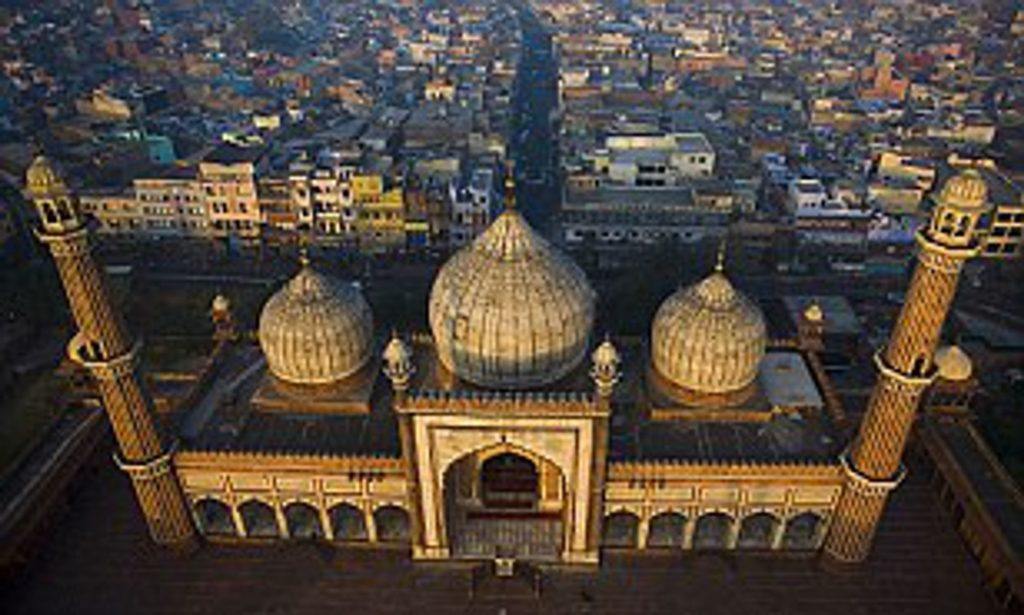

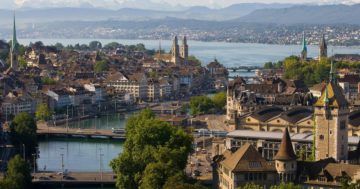

The book is mainly set in two countries: India and Switzerland. And could any two cities be as different as Delhi and Zurich?

Ah, Zurich.

The orderly, fairytale town located along the Limmat River, where on clear days, you can see the snow-capped peaks of the alps in the distance. It is a place where climate disaster feels a million miles away!

A strange choice to locate the new Ministry of the Future. Wouldn’t it be more compelling to locate the Ministry in Delhi, where climate disaster is already on top of people?

The Ministry of the Future is run by Mary Murphy, former foreign minister of Ireland. She and Frank are the main protagonists in this novel composed of 106 short chapters with continually shifting points of view. From the third-person point of view narration of the two protagonists, the book shifts to a multitude of first-person point of view eye-witnesses and experts. These other chapters are mainly devoted to technical topics on subjects like blockchain, Jevon’s Paradox, wildlife extinction, the GINI Index, happiness indexes, and many various types of geo-engineering projects that governments are undertaking to address the problems.

I had never read a book like this and was going to call it “a collage” or polyphonic, when I learned that Amy Brady of the Chicago Review of Books described the style as heteroglossia or polyvocal. In addition to the two main character arcs, the plot includes lectures, radio interviews, riddles, and meeting notes from the Ministry. It is a very effective way to imagine the end of the world in the form of a multiplicity of voices and from so many oblique angles.

4.

4.

To be clear, concluding in brief: there is enough for all so there should be no more people living in poverty. And there should be no more billionaires. Enough should be a human right, a floor beneath which no one can fall; also ceiling above which no one can rise. Enough is a good as a feast — or better.

Arranging the situation is left as an exercise for the reader. —KSR

5.

More than anything else, Ministry of the Future is a novel that explores the end of capitalism. The book is dedicated to KSR’s PhD advisor, the Marxist political theorist and literary critic Frederick Jameson, who is attributed as saying something to the effect that, “It is easier to imagine the end of the world than to imagine the end of capitalism.”

In an interview with Jacobin Magazine, KSR talks about his desire to explore—within the confines of the imaginary world of his novel—ways in which the nations could shift from a capitalism to a post-capitalist version of socialism, one which treats the biosphere as part of our extended body.

For example, some characters look at the federation of workers’ cooperative, the Mondragon, in the Basque region. I was interested in learning about their agreed-upon wage ratios between executive work and field or factory work which earns a minimum wage. As is well-known, the United States has the highest disparity in the developed world between executives and workers within companies. There is no federal regulation, and so we see companies like McDonald showing a ratio of 3,101:1. While Japan and Germany also do not have federal regulations on wage disparity within corporations, both countries have much flatter gaps, so the people themselves are displaying compassion and a willingness to work for the communal good.

This flat gap is what appealed to KSR about the Mondragon model, which has ratios ranging from 3:1 to 9:1 in different cooperatives and average 5:1.

He also looks at the land tenure and workers’ rights in Kerala, because India is so central to the book’s action as a leader of the transition to dramatic climate action.

Nicolas Chorier

6.

Hatred of the other is also quite obviously manifested in such a reaction. The name for this response comes from Wagner‘s opera Götterdämmerung, which ends with the old gods of the pre-Christian Norse mythology destroying the world as they die, in a final murderous and suicidal auto-da-fé. A folk translation of this word into English has it as “the God-damning of the world,” although this makes us use of a false cognate and the German actually means “the twilight of the gods,” and is Wagner‘s German neologism for the Norse word Ragnarok. —KSR

7.

Because there are people whose actions are harming the rest of humanity, not to mention the planet itself, Frank and many like him believe that the only way forward is asymmetrical warfare, acts of eco-terrorism, and eco-assassination. This is how Frank and Mary’s paths first cross, when he kidnaps her and spends a night trying to reason with her about what is at stake.

You’re not doing everything you can, and what you are doing isn’t going to be enough.’ He leaned toward her again and captured her gaze, his eyes bloodshot and bugging out, pale tortured blue eyes scarcely held in by his sweating red face — transfixing her — ‘Admit it!’”

This will affect her profoundly.

A private jet owned by a rich man–boom,

A coal-fired power plant in China–boom.

A cement factory in Turkey, boom. A mine in Angola, boom. A yacht in the Aegean, boom. A police station in Egypt, boom. The Hotel Belvedere in Davos, boom. An oil executive walking down the street, boom. The Ministry for the Future’s offices, boom.

Wait?

The terrorism is aimed at changing the world. But it is quickly apparent that this means changing capitalism.

This will include trying to destroy commercial air travel by using drones to bring down airliners; bioterrorism against slaughterhouses in countries that eat unsustainable amounts of beef, like the UK, Brazil and the US; industrial sabotage of coal plants; and yes– targeted assassination of politicians and CEOs.

In my favorite chapter, “Doubtful in Davos,” we are back in Switzerland again and a bunch of eco-terrorists take over a Davos gathering and hilariously turn it into a kind of re-education camp. The Davos crowd is simply not very likable.

8.

Sikkhim became a state with fully organic agriculture between 2003 and 2016, aided by the scholar-philosopher-feminist-permaculturist Vandana Shiva, an important figure from any of us in India. Of course Sikkim is the least populated Indian state, with less than a million people, and the third smallest in economic terms. But it grows more cardamom than any place but Guatemala, and one of its names as Bayul Demazong, “the hidden valley of rice,“ bayuls being sacred hidden valleys in Buddhist lore, including Shambala and Khembalung. . Sikkim is precisely this kind of magical place, and it’s a version of organic agriculture, one aspect of permaculture generally, became of interest across India in mid-century, as part of the Renewal And the New India, and the making of a better world. –KSR

9.

Several years ago, Tim Kreider in the New Yorker called KSR our greatest living political novelist. He points out that,

Sometime in the past couple of generations, capitalism’s victory over our hearts and minds seems to have become complete, in that hardly anyone even notices it anymore. It’s a monoculture, taken for granted, like monogamy, or monotheism, or having one sun. It’s hard to think of any “serious” literary writers in the United States under the age of fifty who engage the big political issues of our time as directly as Boomer authors like Paul Auster (“Leviathan”), Thomas Pynchon (“Vineland”), or Robert Stone (“A Flag for Sunrise”), let alone in the way that muckraker novelists like Upton Sinclair used to. When we call literary writers “political” today, we’re usually talking about identity politics. If historians or critics fifty years from now were to read most of our contemporary literary fiction, they might well infer that our main societal problems were issues with our parents, bad relationships, and death.

This is precisely what is so exciting about KSR.

As a side note, when I started taking creative writing programs at UCLA, I began reading more American fiction. My background is in Japanese literature and linguistics. And I can say, I have never been much of a fan of contemporary American literature. In my classes at UCLA, it dawned on me that in American novels, the world is a kind of backdrop to the inner lives of the characters. There is an almost obsessive fixation on what is called character arcs that before my classes I would have associated more with romance novels than serious literature. Later, looking into getting an MFA, I was struck by an absence of the political and philosophical novel. And that is when I learned about the connection between the CIA and the Iowa Workshop. I don’t think many other countries have MFA programs like we do here in the US –so this point about KSR’s commitment to the political is well worth thinking about.

This is what led me–and perhaps what also led KSR—toward speculative fiction.

The book is an idea book in the best possible way. One can only imagine how many scientific papers and academic books he must have read to write Ministry of the Future.

Another thing that struck me since I returned to the United States almost ten years ago is the growing difficulty people have holding many ideas in their mind at once. I think it is the corporate media that feeds this tendency to frame everything in good guys versus bad guys. Memes. Some thinkers refer to this as a kind of epistemological crisis whereby people seem less capable to view complex issues in nuanced, fact-checked ways which allow for multiple perspectives and multiple solutions that are worth both discussing and exploring empirically. Scientists don’t think in terms of single fixes to climate change, while wagging their fingers at other options.

At this point, as KSR says: To Fight Climate Change, We Will Need Every Arrow in Our Quiver. And that is precisely right, I think. We need to hit the problem from various angles and try to push down the amount of carbon emitted using all we’ve got –from city planning and economics to multiple kinds of technologies and geo-engineering “fixes.”. And so in the novel, we follow along with experiments in a blockchain-regulated “carbon coin,” that would be paid to states, corporations, and individuals who succeed in sequestering carbon instead of spewing it into the atmosphere; massive re-wilding (half earth), and the replacement of gasoline-fueled airplanes with airships (we saw these large helium balloons in one of his previous novels as well); similarly, there are tanker ships fueled by wind and solar; and the replacement of predatory social media with publicly owned platforms.

And did I mention the nationalizing of banks?

So, is this the end of the world?

Well, according to KSR, it is the end of the world — and this means the end of global capitalism. We all know that our model of endless growth, personal optimization and “consumerism as citizenship” is simply not sustainable. Not for the planet and not even for those winning the race to the top. It is time to herald in a new age.

Although the stakes are dire, his message remains optimistic.

++

Further reading about other thinkers heralding in a new age: An Inter-Species Crowd: How To Talk To Animals And Space Aliens

How can we be grounded locally and see ourselves as part of an inter-dependent community of family businesses and family farms– an inter-species crowd even? And most importantly, how can we raise our kids not to become producers and consumers in the great war between the haves and have nots but as part of an interconnected world where time is no longer money. And to me, this has always been the saddest thing of all: that we force our kids to jump through these hoops that we know in our hearts only further add to the alienation that they will feel with nature and each other.

Rutgers EOAS Rountable with KSR and Naomi Klein

The 2,000 Watt Society and the Island of Winds (From 2009)

Other books that changed the way I look at the world

Images of beautiful India by Nicolas Chorier taken by attaching a camera on a kite. A bird’s eye view?