by Alexander C. Kafka

Is loneliness a choice? Is love?

Is loneliness a choice? Is love?

Such timeless questions resonate particularly a year and a half into the coronavirus pandemic as we continue to weigh the risks and rewards of companionship, of intimacy, and calculate our capacity for solitude. Those quandaries propel the bittersweet romantic, sometimes droll meditation I’m Your Man, a new German film directed by Maria Schrader from a script she wrote with Jan Schomberg off a short story by Emma Braslavsky.

Alma (Marren Eggert) is an anthropologist pressured into participating in an evaluation of humanoid, robotic, made-to-order mates. Hers is a dapper, dignified database named Tom (Dan Stevens), who can rumba, recite Rilke, or cite a just-published journal article written by Brazilian cuneiform experts. Alma’s tastes, atop the crowd-sourced desires of millions of other women, dictate his algorithms, which are fine-tuned as he interacts with her. Out of the box, he comes on a little strong. “You’re a very beautiful woman, Alma,” he says upon first meeting her. “Your eyes are like two mountain lakes I could sink into.” But he’s a quick study and soon tones it down. Read more »

Presidency College had a good Department of Economics and Political Science. I’d say that the teaching standard at my time there would compare quite favorably with the standard I found later when teaching undergraduate classes in Berkeley. I remember in my first lecture in Berkeley in a large undergraduate class I was using some bit of calculus. After my class a female student came to see me to complain about the use of calculus in class. I told her that I was not using any advanced calculus, so if she brushed up her high school-level calculus she should have no difficulty in following the class. She said that in her high school in Carmel, a California coastal town, there was the option to take either calculus or yoga, and she had chosen the latter. I told her, unhelpfully, that this was a choice unheard-of in the land of yoga, India, and, I thought to myself, certainly in Presidency College.

Presidency College had a good Department of Economics and Political Science. I’d say that the teaching standard at my time there would compare quite favorably with the standard I found later when teaching undergraduate classes in Berkeley. I remember in my first lecture in Berkeley in a large undergraduate class I was using some bit of calculus. After my class a female student came to see me to complain about the use of calculus in class. I told her that I was not using any advanced calculus, so if she brushed up her high school-level calculus she should have no difficulty in following the class. She said that in her high school in Carmel, a California coastal town, there was the option to take either calculus or yoga, and she had chosen the latter. I told her, unhelpfully, that this was a choice unheard-of in the land of yoga, India, and, I thought to myself, certainly in Presidency College. I live on an island. It happens to be a rather densely populated island, with a surface that seems largely covered by steel, masonry, glass, and architectural curtain wall, with nary a coconut or palm tree in sight. Still, it’s an island.

I live on an island. It happens to be a rather densely populated island, with a surface that seems largely covered by steel, masonry, glass, and architectural curtain wall, with nary a coconut or palm tree in sight. Still, it’s an island.

“The Iliad, or The Poem of Force” is a now-canonical lyrical-critical essay by the French anarchist and Christian mystic, Simone Weil. In it, Weil critiques the

“The Iliad, or The Poem of Force” is a now-canonical lyrical-critical essay by the French anarchist and Christian mystic, Simone Weil. In it, Weil critiques the

In the late 1960s and early 70s, Pocatello, Idaho, was one of the fastest growing towns in the United States. It was, and still is, a bland little place in the arid montane region of the American West. I don’t know why it mushroomed then; it has since stagnated and even shrunk. Nevertheless, the summer I turned four, my family was one among many who moved to reside there. Our little red brick house, still unfinished on the day we moved in, was the last house at the end of a newly laid street, still half-empty of houses. Our street stretched like a solitary finger into a kind of wilderness, an austere, high-desert landscape that surrounded our foundling residential colony. From my vantage as a child, preoccupied with the flowers, spiders, and thistles that stuck to my socks, I would see this place transformed.

In the late 1960s and early 70s, Pocatello, Idaho, was one of the fastest growing towns in the United States. It was, and still is, a bland little place in the arid montane region of the American West. I don’t know why it mushroomed then; it has since stagnated and even shrunk. Nevertheless, the summer I turned four, my family was one among many who moved to reside there. Our little red brick house, still unfinished on the day we moved in, was the last house at the end of a newly laid street, still half-empty of houses. Our street stretched like a solitary finger into a kind of wilderness, an austere, high-desert landscape that surrounded our foundling residential colony. From my vantage as a child, preoccupied with the flowers, spiders, and thistles that stuck to my socks, I would see this place transformed. The chill in the early morning air hinted of autumn, yet the intensity of the rising sun promised summer heat. Black Tupelo and Red Maple leaves teased memories of fall with premature wisps of yellow and orange. The sky was a depthless cobalt blue, its crystallinity making everything and everyone shimmer. It makes sense that the stunning weather on that particular morning should become a shared referent for our collective dissonance, a common denominator of terror, mourning, and remembrance spanning two decades.

The chill in the early morning air hinted of autumn, yet the intensity of the rising sun promised summer heat. Black Tupelo and Red Maple leaves teased memories of fall with premature wisps of yellow and orange. The sky was a depthless cobalt blue, its crystallinity making everything and everyone shimmer. It makes sense that the stunning weather on that particular morning should become a shared referent for our collective dissonance, a common denominator of terror, mourning, and remembrance spanning two decades. Margot Livesey’s The Boy in the Field is a mystery novel in the broadest sense of that literary term. Yes, the novel begins with the discovery of a crime, and the perpetrator remains at large for most of the narrative. Yet the “what happened next” of a standard mystery novel concentrates on the three siblings who came upon the victim lying in a field, the reverberations of that event on their young lives, and of the family they are a part of. “Mystery” can reside within all of us, to locate or evade, and that is the deeper reveal that Livesey hunts for in this wise and haunting book.

Margot Livesey’s The Boy in the Field is a mystery novel in the broadest sense of that literary term. Yes, the novel begins with the discovery of a crime, and the perpetrator remains at large for most of the narrative. Yet the “what happened next” of a standard mystery novel concentrates on the three siblings who came upon the victim lying in a field, the reverberations of that event on their young lives, and of the family they are a part of. “Mystery” can reside within all of us, to locate or evade, and that is the deeper reveal that Livesey hunts for in this wise and haunting book.

As we look toward wending our way out of the COVID-19 global health crisis, what tools can we use to make sense of what we are experiencing? For if there is anything self-evident in our current predicament, it is that any given field—medicine, sociology, political science, psychology—are insufficient in isolation. “Pandemic,” from the Greek πάνδημος, means of or belonging to all the people; and the challenges of this pandemic compel us to take a pan-disciplinary approach.

As we look toward wending our way out of the COVID-19 global health crisis, what tools can we use to make sense of what we are experiencing? For if there is anything self-evident in our current predicament, it is that any given field—medicine, sociology, political science, psychology—are insufficient in isolation. “Pandemic,” from the Greek πάνδημος, means of or belonging to all the people; and the challenges of this pandemic compel us to take a pan-disciplinary approach.

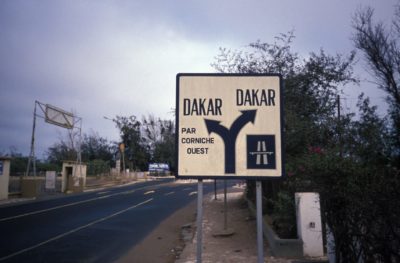

It is time to go home. You can pull down the window shade for some relief; then it’s only 100 degrees. An Air Burkina Fokker F28 has sidled up to join us on the tarmac in Bamako, Mali. Not quite home yet.

It is time to go home. You can pull down the window shade for some relief; then it’s only 100 degrees. An Air Burkina Fokker F28 has sidled up to join us on the tarmac in Bamako, Mali. Not quite home yet. There’s a lot we can learn about today’s America by observing the Mormon Church.

There’s a lot we can learn about today’s America by observing the Mormon Church.

I was there when they first went up. From my south-facing bedroom on Morton Street in the village, I watched them grow, floor by floor, to a height unimaginable for that time. When they were finished, I began to measure their height against their distance from my bedroom. If they fell over, would they reach me? Not only was I ignorant of structural engineering, I never gave a thought to what would happen to the people inside if they did fall over. Years later I would learn that they didn’t fall over, they fell down. This time my thoughts were with those people inside.

I was there when they first went up. From my south-facing bedroom on Morton Street in the village, I watched them grow, floor by floor, to a height unimaginable for that time. When they were finished, I began to measure their height against their distance from my bedroom. If they fell over, would they reach me? Not only was I ignorant of structural engineering, I never gave a thought to what would happen to the people inside if they did fall over. Years later I would learn that they didn’t fall over, they fell down. This time my thoughts were with those people inside.