by Raji Jayaraman

Audio version

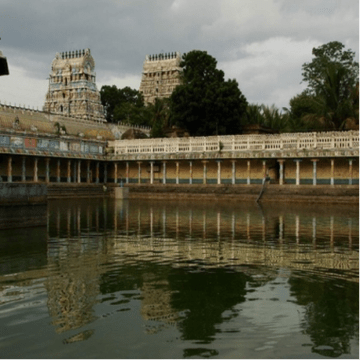

When you say you have an ancestral temple, it sounds fancy. To be fair, some are. My mother’s ancestral temple, the Vaitheeswaran Koil, is a vast complex with five towers and hall after cavernous hall housing both worshippers and elephants. The temple is dedicated to Shiva in his incarnation as a healer. Perched on the banks of the Cauvery river, a dip in any one of its eighteen water tanks is said to cure all ailments. Dedicated to Mars, it is one of only nine ancient Tamil temples devoted to the planets. (Before you get excited about the prescience of the nine, I feel obliged to inform you that two of them are the sun and the moon, and another two are “Rahu” and “Ketu” who reside somewhere between the sun and moon, causing eclipses.) It has gold plated pillars; emerald encrusted deities; and inscriptions dating back to at least the Chola period in the twelfth century. All very impressive.

I would bask in the reflected glory except that I don’t stem from a matrilineal religious tradition, so my ancestral temple is said to be my father’s. Our parents’ biannual visits to India always included a temple tour with a mandatory visit to the ancestral temple. The itinerary never included Vaitheeswaran Koil, and looking back, I can see why. My ancestral temple was in a village called Tholacheri, and I use the term “village” loosely. Tholacheri contained four or five mud-walled, thatched roof structures surrounding three sides of a viscous pond. On the fourth side lay the temple compound.

The compound’s architectural ensemble comprised the temple itself, consisting of a small anteroom and alcove; a hut that served as the priest’s residence; and four or five giant-sized painted terracotta statues of Ayyanar deities. These statues were armed with machetes. They had bulbous eyes, protruding tongues, and outsized fangs. As an adult they looked almost comical but as children they struck the fear of God in us, which I suppose was the whole point.

Our parents always rented a car and driver to take us to Tholacheri. We would pile in, along with my increasingly rotund grandmother and one reluctant child-representative from families on my father’s side. Including the driver, this made a total of four adults and six children, so my parents always hired an Ambassador car. It had bench seats in the front and back and a steering wheel gear shift, which meant that we could squeeze in more or less symmetrically at both ends. Air conditioning in the thirty-plus-degree temperature took the form of open windows, so our faces were whipped by the carefully oiled, wind-blown tresses of our cousins, as our immobilized bottoms stuck painfully to the vinyl seats.

I don’t recall ever looking at a road map as a child. If they existed then our parents hadn’t heard of them, so finding Tholacheri was always a challenge. We’d set off from Chennai at dusk and stop just after dawn in the village of Thiruthirapundi, which was about twenty kilometres away from our destination, to ask for directions. That stop was rarely helpful because although nobody had ever heard of Tholacheri, saying as much was considered rude.

In truth, Thiruthirapundi stops were more about breakfast and puja-shopping than anything else. Words cannot describe the pleasure of a meter-high tumbler of milky South Indian coffee and a plate overflowing with paper dosai, after a night of seated dormancy wedged between grandma and cousin, on a single lane highway with only a car horn and flashing high beams separating you from oncoming traffic.

On one of these trips, when we were in the market buying flowers, incense, and fruit for the rituals that lay ahead of us, my father noticed a stall selling birds. They were dyed in bright hues of pink, yellow and blue to attract buyers and deter predators. He suggested that we purchase a small flock, the idea being that after the puja we would symbolically release them from captivity. It was a poetic suggestion completely out of character with my dad, who is an accountant. We looked at him quizzically but quickly agreed, lest he change his mind. We piled back into the Ambassador, accompanied this time by ten psychedelic songbirds, shitting in terror, and chirping tunelessly in their too-small cage.

Arriving at Tholacheri a full two hours later, we were greeted by four or five mangy dogs. One of them was firmly attached to the priest, because I remember seeing her biannually. The rest was an assortment of strays. On a good day, people from neighbouring villages brought a goat to sacrifice and cook after their puja, so the dogs had good reason to loiter.

After the canine reception, we took the obligatory ritual bath in the swampy pond in a show of piety matched only by modesty that demanded that we bathe fully clothed. After a hasty dunk, which turned our colourful cotton wear into a uniform shade of muck, we hobbled back to the compound barefooted, dodging cowpats, dripping wet. It was a miracle that cholera didn’t cull us in the ten meters separating the pond from the temple.

Inside the temple anteroom, we sat cross-legged in a shivering heap on the cold concrete floor, which was covered with pellets of bat excrement, retching at the stench. It was dark, with oil lamps in the alcove that housed the idols casting shadows over us as the priest performed the rites. The contrast between this and Vaitheeswaran couldn’t have been starker. During the puja, our heads remained bowed. It was a pose that our parents mistook for devotion but was in fact calculated to avoid having the occasional jets of urine, emanating from the bats housed in the pitch-black rafters overhead, from landing on our faces. When the seemingly interminable puja came to an end, we rushed outside for sun and air.

Our father took the bird cage out of the car and placed it on the stone wall. He figured the height would give the birds a leg up. We stood in a gleeful circle at a respectful distance from the cage. We didn’t want to frighten the birds. He opened the cage and took a step back to give them space. A couple of brave birds hopped to the exit. We stood there in breathless anticipation of an Indian village version of the white doves in the opening ceremony of the Olympic games. The first bird sprang from the cage, but it instead of soaring into the clear blue sky, it flopped inelegantly to the ground. We realized, to our horror, that its wings had been clipped. In no time, the second bird followed, and then, like lemmings the third and the fourth, until all ten birds lay on the ground, flopping about helplessly. The drop from the wall that was to have served as their springboard, was considerable. They seemed dazed. We stood paralyzed, staked to the ground in shock, for what couldn’t have been more than a few seconds. Before we could even think of what to do next, the dogs charged in and had their fill.

The carnage left our father shaken. He is a superstitious, God-fearing man. We were not permitted to leave the house during “Rahu Kaalam”—a randomly placed inauspicious time of day attributed to the eponymous planet-God. Our father always drove two centimetres forward before reversing from the garage, lest fate get the wrong idea. We weren’t allowed to sneeze in singles because that was bad luck, so we had to fake a second sneeze if we only had one genuine item in stock. My sister internalized this to such an extent that, to this day, she sneezes in groups of five or not at all. Our mother tried to comfort him with the idea that the birds were an offering to the Gods. He nodded but appeared unconvinced. We squinted away our tears quickly for fear of exacerbating our father’s already heightened state of anxiety because, well,…the poor birds.

The good news is that not all our temple visits ended that ignominiously. There was the time when our grandmother caught us red handed, partaking in the sacrificial goat feast, and correctly accused us of being closet non-vegetarians. Our father tried to convince her that sampling was our sacred obligation. She was skeptical, but the villagers were gracious about our hypocrisy and the goat curry was delicious. There was the visit after the temple renovation, where we entered the anteroom to discover that the smoke-stained, lamp-lit interior had been replaced by white bathroom tiles and a tube light. That startled us. Judging from the brightly lit urine-streaked walls the bats were more resilient, but the smell of Dettol futilely applied to the tiles beat theirs. The early afternoon views of the countryside on our return journey always made the drive seem less life threatening. Our memories of the septic-brown pond receded at the sight of electric-green rice fields and brick-red earth.

It was definitely not Vaitheeswaran Koil. I didn’t even know the temple deity’s name as a kid. Our father tells me it was Karthyayani—the “mother goddess” who probably has a temple in every Indian village. My ancestral temple had no grandeur, but that doesn’t pain me in the least. It didn’t rise to great heights, but there is no question of roots.