Gabriel’s Mad Ave. Apocalyptic Horn

…. “I’m still dwelling on how ironic all the feverish proclamations of capitalism

…. are going to look someday.” —Justin E. H. Smith, Philosopher

I’m through with dumpster dinners

at the corner of Wall Street and New

I’m so unsold by the Coke sign’s faded blush

that thrusts from desiccated dollar dunes,

an embarrassment, a crass embellishment

stuffed in the cleavage of a spent whore

who promised eternal bliss but ended a hag

with smeared lips and hellish scent,

cyclone’s gone that slew the sacred cow

when gangs of suited crooks blew through

with milking stools to sit beside her tits of gold

with digits itching to draw her dry

with lips pursed to suck her blood

with a singeing sort of lust, twisted,

a rusty screw that drills down and down

until nothing’s left to suck or bust,

I’m done . . . we’ve lurched too long through

spoiled earth as Gabriel’s Mad Ave.

apocalyptic horn rather croaked than blew

.

by Jim Culleny

9/13/14

Sometimes our American ideas about social problems and how to fix them are downright medieval, ineffective, and harmful. And even when our methods are ineffective and harmful, we are likely to stick to them if there is some moralistic taint to the issue. We are the children of Puritans, those refugees who came to America in the 17th century to escape King Charles.

Sometimes our American ideas about social problems and how to fix them are downright medieval, ineffective, and harmful. And even when our methods are ineffective and harmful, we are likely to stick to them if there is some moralistic taint to the issue. We are the children of Puritans, those refugees who came to America in the 17th century to escape King Charles.

One of my earliest memories was of Christmas Eve in 1954. I was about 3 or 4 years old, playing under a table at my grandmother’s house. My sister and a cousin were with me, playing with a small wooden crate filled with straw. The crate represents the manger in the stable in Bethlehem 1,954 years ago, where the animals welcomed the baby Jesus, since there were no rooms in the inn. We three kids were waiting for the adults to come to the table to join us for Wigilia, the traditional Christmas Eve feast, after which we would move to the living room, sing Polish Christmas Carols, and wait for an uncle disguised as Santa to arrive with presents for everyone.

One of my earliest memories was of Christmas Eve in 1954. I was about 3 or 4 years old, playing under a table at my grandmother’s house. My sister and a cousin were with me, playing with a small wooden crate filled with straw. The crate represents the manger in the stable in Bethlehem 1,954 years ago, where the animals welcomed the baby Jesus, since there were no rooms in the inn. We three kids were waiting for the adults to come to the table to join us for Wigilia, the traditional Christmas Eve feast, after which we would move to the living room, sing Polish Christmas Carols, and wait for an uncle disguised as Santa to arrive with presents for everyone. Over the years I have heard many stories about Mahalanobis. One relates to his youth. He and Sukumar Ray (Satyajit Ray’s father, a pioneer in Bengali literature of nonsense rhymes and gibberish) were the two contemporary Brahmo whiz kids active in literati circles. They used to arrange regular meetings at someone’s home for serious discussion. But as usually happens in such Bengali middle-class gatherings, much time was taken up in the serving and enjoyment of food delicacies. Mahalanobis objected to this and said this was leaving too little time for discussion. So he sternly announced that from now on no food should be served in the meeting. For the next couple of times people morosely accepted the rule. But Sukumar subverted it, by one time arriving a little early and persuading the food-preparers in the household (usually women) that for the sake of the morale in the meeting, food-serving should be resumed. By the time Mahalanobis arrived, everybody was relishing the delicacies, which infuriated him, but he gave up.

Over the years I have heard many stories about Mahalanobis. One relates to his youth. He and Sukumar Ray (Satyajit Ray’s father, a pioneer in Bengali literature of nonsense rhymes and gibberish) were the two contemporary Brahmo whiz kids active in literati circles. They used to arrange regular meetings at someone’s home for serious discussion. But as usually happens in such Bengali middle-class gatherings, much time was taken up in the serving and enjoyment of food delicacies. Mahalanobis objected to this and said this was leaving too little time for discussion. So he sternly announced that from now on no food should be served in the meeting. For the next couple of times people morosely accepted the rule. But Sukumar subverted it, by one time arriving a little early and persuading the food-preparers in the household (usually women) that for the sake of the morale in the meeting, food-serving should be resumed. By the time Mahalanobis arrived, everybody was relishing the delicacies, which infuriated him, but he gave up.

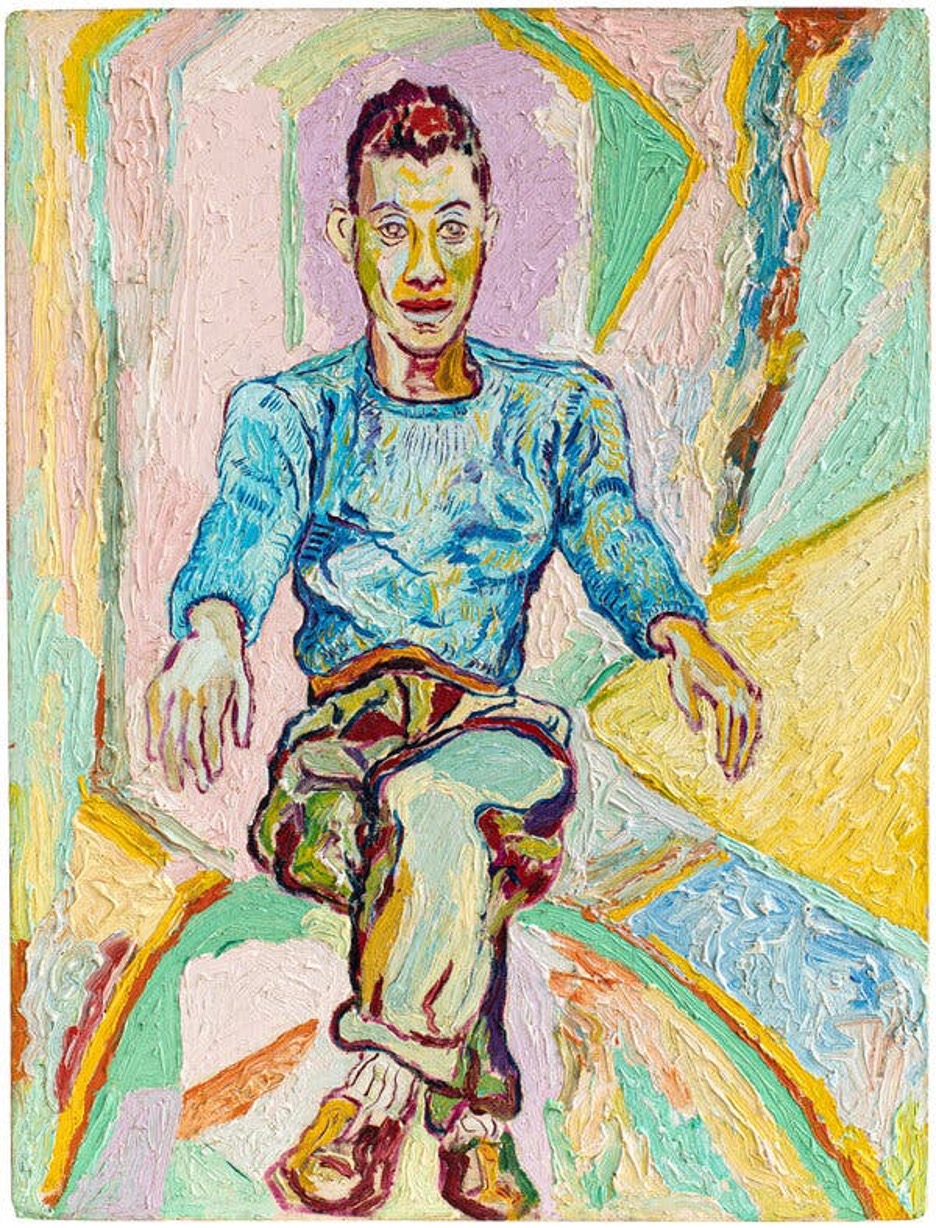

Beauford Delaney. James Baldwin (Circa 1945-50).

Beauford Delaney. James Baldwin (Circa 1945-50). A couple of weeks ago, on the pages of this website,

A couple of weeks ago, on the pages of this website,