by Thomas O’Dwyer

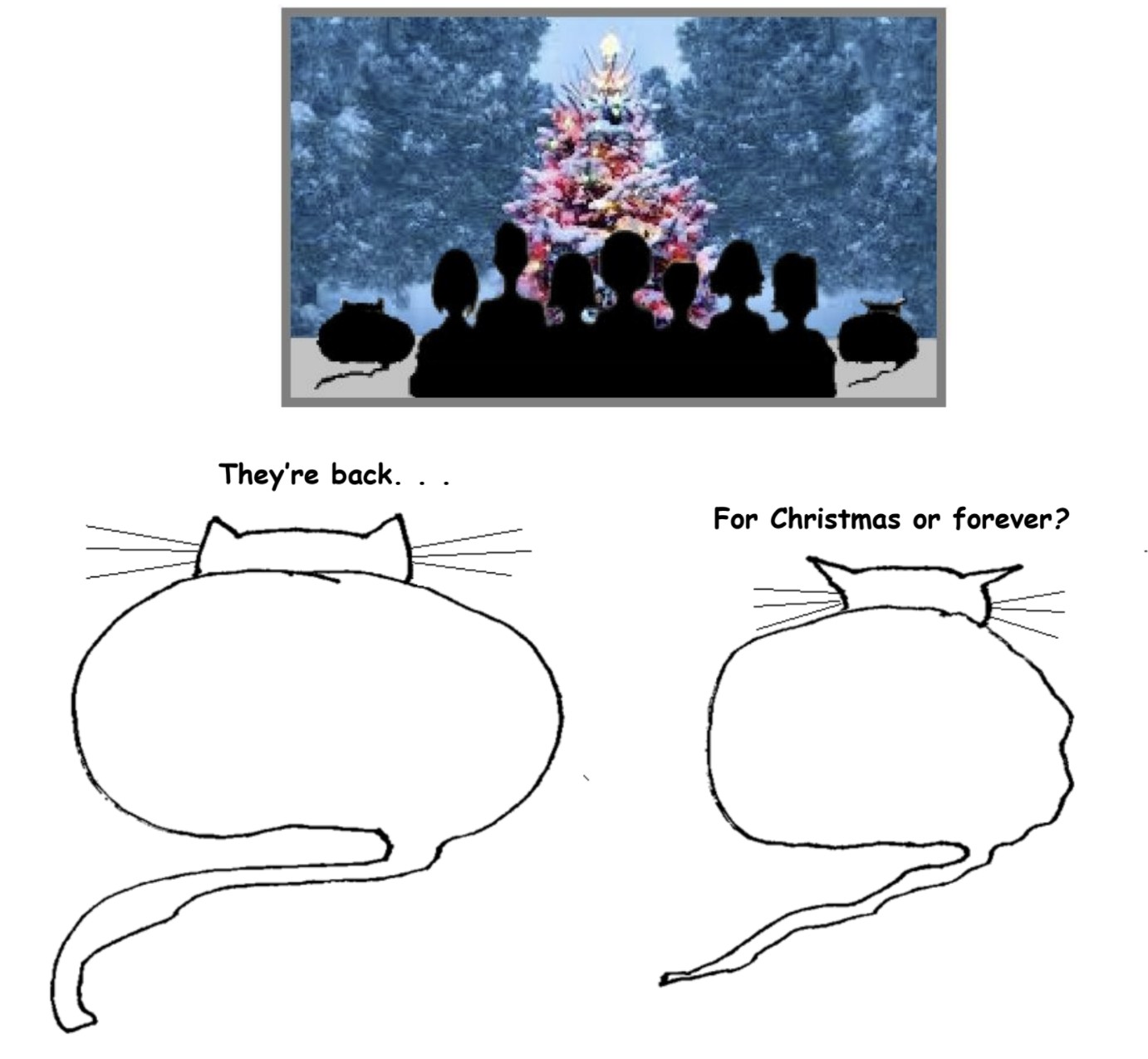

Christmas is one of the most remarkable festivals of human invention, a fact acknowledged by non-Christians no less than people of that faith. The arbitrary association of the birth of Jesus with December 25 merely added a new legend to a festival that was already thousands of years old in a variety of iterations that had the winter solstice as the common denominator. The traditions attached to the holiday have evolved down centuries of differing beliefs, legends, politics, lifestyles — though “tradition” may be too kind a word for the crass commercialism of the modern Christmas season in the United States of Dollarmania. It’s a far cry from Neolithic days and the people who built Stonehenge on Salisbury Plain in England and Newgrange in the Boyne Valley of Ireland, who oriented massive monuments to intercept the sunrise on the morning of the midwinter solstice. Archaeologists have revealed that the residents of Durrington Walls near Stonehenge held large festivals coinciding with this turning point from shortening to lengthening days. And so it began, the accretion of customs, festivities, eating and drinking, link after link down the chain of time to our “Ho ho ho! Buy buy buy!”

Romans dedicated the feast to Saturn, and medieval Europeans booted him aside to celebrate Christ’s Mass, dovetailing devotion with drunken partying. Victorians shaped the modern Christmas sentimentally chronicled by Charles Dickens. Drunken public partying of past centuries gave way to sober child and family-centred celebrations inspired by Queen Victoria, Prince Albert and their nine children. Albert introduced the Christmas tree from his native Germany. Children’s gifts, Christmas cards, crackers, and plum pudding followed, and turkey replaced the traditional goose for dinner. Santa Claus, who had morphed from Saint Nicholas of Myra in Byzantium via Sinterklaas, whom Dutch settlers brought to New York, now appeared on his reindeer sleigh in the Christmas Eve sky over England. American poet Clement Clarke Moore had defined the concept of Santa that still endures — costume, sleigh, reindeer, global gift-giving, chimney antics — in his poem A Visit from St. Nicholas (also called The Night Before Christmas). Read more »

Sometimes our American ideas about social problems and how to fix them are downright medieval, ineffective, and harmful. And even when our methods are ineffective and harmful, we are likely to stick to them if there is some moralistic taint to the issue. We are the children of Puritans, those refugees who came to America in the 17th century to escape King Charles.

Sometimes our American ideas about social problems and how to fix them are downright medieval, ineffective, and harmful. And even when our methods are ineffective and harmful, we are likely to stick to them if there is some moralistic taint to the issue. We are the children of Puritans, those refugees who came to America in the 17th century to escape King Charles.

One of my earliest memories was of Christmas Eve in 1954. I was about 3 or 4 years old, playing under a table at my grandmother’s house. My sister and a cousin were with me, playing with a small wooden crate filled with straw. The crate represents the manger in the stable in Bethlehem 1,954 years ago, where the animals welcomed the baby Jesus, since there were no rooms in the inn. We three kids were waiting for the adults to come to the table to join us for Wigilia, the traditional Christmas Eve feast, after which we would move to the living room, sing Polish Christmas Carols, and wait for an uncle disguised as Santa to arrive with presents for everyone.

One of my earliest memories was of Christmas Eve in 1954. I was about 3 or 4 years old, playing under a table at my grandmother’s house. My sister and a cousin were with me, playing with a small wooden crate filled with straw. The crate represents the manger in the stable in Bethlehem 1,954 years ago, where the animals welcomed the baby Jesus, since there were no rooms in the inn. We three kids were waiting for the adults to come to the table to join us for Wigilia, the traditional Christmas Eve feast, after which we would move to the living room, sing Polish Christmas Carols, and wait for an uncle disguised as Santa to arrive with presents for everyone. Over the years I have heard many stories about Mahalanobis. One relates to his youth. He and Sukumar Ray (Satyajit Ray’s father, a pioneer in Bengali literature of nonsense rhymes and gibberish) were the two contemporary Brahmo whiz kids active in literati circles. They used to arrange regular meetings at someone’s home for serious discussion. But as usually happens in such Bengali middle-class gatherings, much time was taken up in the serving and enjoyment of food delicacies. Mahalanobis objected to this and said this was leaving too little time for discussion. So he sternly announced that from now on no food should be served in the meeting. For the next couple of times people morosely accepted the rule. But Sukumar subverted it, by one time arriving a little early and persuading the food-preparers in the household (usually women) that for the sake of the morale in the meeting, food-serving should be resumed. By the time Mahalanobis arrived, everybody was relishing the delicacies, which infuriated him, but he gave up.

Over the years I have heard many stories about Mahalanobis. One relates to his youth. He and Sukumar Ray (Satyajit Ray’s father, a pioneer in Bengali literature of nonsense rhymes and gibberish) were the two contemporary Brahmo whiz kids active in literati circles. They used to arrange regular meetings at someone’s home for serious discussion. But as usually happens in such Bengali middle-class gatherings, much time was taken up in the serving and enjoyment of food delicacies. Mahalanobis objected to this and said this was leaving too little time for discussion. So he sternly announced that from now on no food should be served in the meeting. For the next couple of times people morosely accepted the rule. But Sukumar subverted it, by one time arriving a little early and persuading the food-preparers in the household (usually women) that for the sake of the morale in the meeting, food-serving should be resumed. By the time Mahalanobis arrived, everybody was relishing the delicacies, which infuriated him, but he gave up.