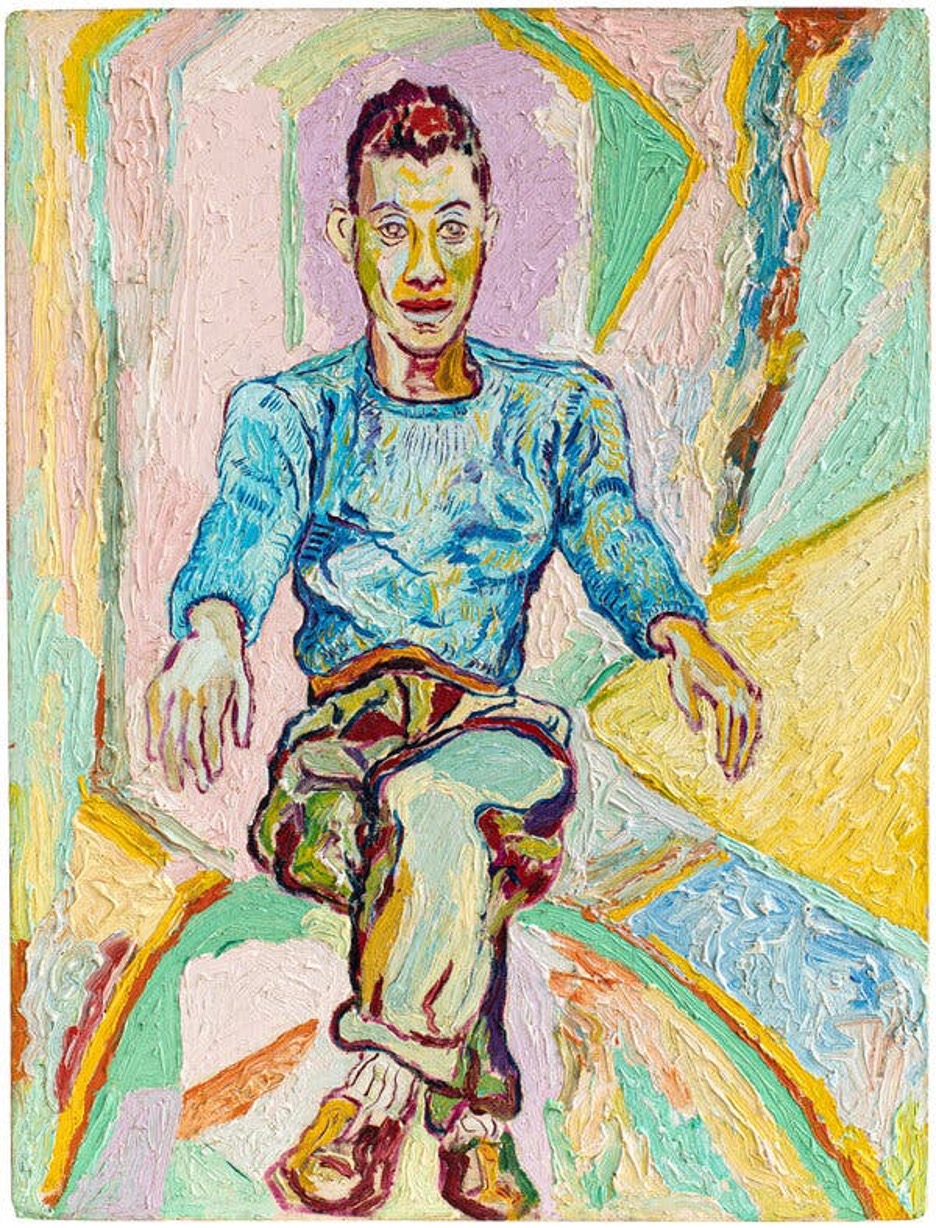

Beauford Delaney. James Baldwin (Circa 1945-50).

Beauford Delaney. James Baldwin (Circa 1945-50).

Category: Monday Magazine

Though we are an aggregator blog (providing links to content elsewhere) on all other days, on Mondays we have only original writing by our editors and guest columnists. Each of us writes on any subject we wish, and the length of articles generally varies between 1000 and 2500 words. Our writers are free to express their own opinions and we do not censor them in any way. Sometimes we agree with them and sometimes we don’t.Below you will find links to all our past Monday columns, in alphabetical order by last name of the author. Within each columnist’s listing, the entries are mostly in reverse-chronological order (most recent first).

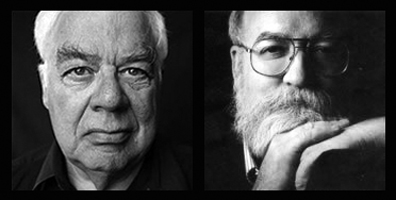

The Philosopher and Pain: The Case of Rorty and Dennett

by Guy Elgat

A couple of weeks ago, on the pages of this website, some critical comments on Richard Rorty’s general argumentative style were made, and, sympathetic to these comments, this inspired me to join the discussion with some criticism of Rorty of my own and, while I am at it, throw in some criticism of Daniel Dennett, for, as will be seen, they both have some mindboggling and implausible things to say about the experience of pain. This, in my view, stems from one of the things they have in common despite their many and substantial differences, namely, their deep animosity to anything Cartesian.

A couple of weeks ago, on the pages of this website, some critical comments on Richard Rorty’s general argumentative style were made, and, sympathetic to these comments, this inspired me to join the discussion with some criticism of Rorty of my own and, while I am at it, throw in some criticism of Daniel Dennett, for, as will be seen, they both have some mindboggling and implausible things to say about the experience of pain. This, in my view, stems from one of the things they have in common despite their many and substantial differences, namely, their deep animosity to anything Cartesian.

The experience of pain, and indeed any qualitative experience at all – what is referred to in philosophical circles with that ugly word “qualia” – is the bugbear of all hard-nosed and tough-minded philosophers who, enamored of the methods and results of the sciences, seek to eliminate or reduce any and every residue of the mental that is subjective, first-person, infallible, private, intrinsic, or indeed, qualitative. These properties, characteristic of the Cartesian mind, though certainly not conceived by Descartes in these very terms, threaten the scientific image of the world where everything is supposed to be objective, quantitative, extrinsic, and open to experimentation, verification and revision. As such, qualitative, first-person experiences are to be, if not explained away, expelled or expunged from any respectable philosophy. And while Rorty himself was not in any way a science-enthusiast, he shared Dennett’s scientifically-infused critical attitude to the Cartesian mind: the Cartesian legacy in the philosophy of mind must (not without some glee) be quashed, no matter the philosophical cost. Read more »

Catspeak

by Brooks Riley

A Sense of Place

by Derek Neal

One of those mysterious concepts that we use as a criterion for judging a novel or film is a “sense of place.” I call it mysterious because it’s so often poorly defined—we recognize it because we can feel it, but what goes into creating it? How can one go about transporting a reader, for example, into a time and place via text? I’m under the impression that if asked this question, most people would mention things like using the five senses to describe a character’s impressions of his or her surroundings, or providing detail via adjectives and adverbs. This may be a gross generalization, but it’s what I’ve gathered from my experience in creative writing courses. It’s also the sense I get from reading short stories in literary journals, which seem to be where aspiring writers publish their attempts at fiction. I often find this writing technically good, but lifeless; it has all the components of effective writing but doesn’t add up to anything compelling. I don’t mean to suggest that I could do better, but I do know what I enjoy reading and what I don’t.

One of those mysterious concepts that we use as a criterion for judging a novel or film is a “sense of place.” I call it mysterious because it’s so often poorly defined—we recognize it because we can feel it, but what goes into creating it? How can one go about transporting a reader, for example, into a time and place via text? I’m under the impression that if asked this question, most people would mention things like using the five senses to describe a character’s impressions of his or her surroundings, or providing detail via adjectives and adverbs. This may be a gross generalization, but it’s what I’ve gathered from my experience in creative writing courses. It’s also the sense I get from reading short stories in literary journals, which seem to be where aspiring writers publish their attempts at fiction. I often find this writing technically good, but lifeless; it has all the components of effective writing but doesn’t add up to anything compelling. I don’t mean to suggest that I could do better, but I do know what I enjoy reading and what I don’t.

Another way to create a sense of place, and this is my preferred method as a reader, is to include an abundance of proper nouns relating to real places, streets, and buildings. I’m not sure why this works. It would seem that this way of writing should only make sense for readers who have visited the places being mentioned, while readers unfamiliar with the locations might feel something lacking and be unable to create an image in their minds. But do we ever really create an accurate image of what we’re reading, or do the words on the page merge with our own ideas and create something unique in the mind of each individual reader? I’d say it’s the latter. Read more »

Monday Photo

Historical Memory 3: The Past and Ireland’s Uncomfortable Present

by Dick Edelstein

The notion of historical memory has to do with the ways in which social groups and nations construct and identify with particular narratives about historical periods or events. This is the third in a series of four articles on this topic. The first two can be found here. In the first I discussed the treatment of archival information on Spanish Civil War casualties and victims, and the activities related to that issue undertaken by the Spanish NGO Innovation & Human Rights. In the second I examined the activities of Fired! Irish Women Poets and the Canon, a collective that worked to redress the exclusion of Irish women writers from the historical record. The present article is not the final one, as I previously announced, because my topic became too broad to fit comfortably in a single piece. In the concluding column, which will be published here in four weeks, I will consider various manifestations in Spain of the issue of historical memory, and I will discuss the perennial conflict between the need to remember and the need to forget, as well as conflicts that arise when different groups appeal to the right to remember.

In this article I discuss several of the embarrassingly large number of recent situations in Ireland in which the issue of historical memory has irrupted into the news and the public awareness. Besides the Fired! movement and the previously discussed Waking the Feminists campaign, these occurrences include the exploitation and abuse of unwed mothers at the Magdalene Laundries, the secret burial of babies in Tuam, the Roman Catholic church cover-up of sexual abuse by priests and nuns, and perennial issues related to British colonial oppression and sectarian conflict in Northern Ireland. Read more »

Charaiveti: Journey From India To The Two Cambridges And Berkeley And Beyond, Part 22

by Pranab Bardhan

All of the articles in this series can be found here.

Though I decided to go back to India, which institution I’d join there took some more time to determine. I had a standing invitation from K.N. Raj at the Delhi School of Economics. Even before I left MIT he asked me to teach a course in MIT’s summer-vacation period. I went and taught part of a course, which had good students (including Amitava Bose, who in his later professional life became close to me, served as a Director of the Indian Institute of Management in Kolkata, and finally lost his long battle against cancer). But I soon found out that the only job Raj could offer me was that of a Readership (Associate Professorship), as a full Professorship was not yet vacant. Amartya-da advised me against accepting a Readership, since in Indian universities there could be ‘many a slip’ even when a Professorship became vacant. I went back to MIT after the vacation, and soon after I got a message from T.N. Srinivasan of the Indian Statistical Institute (ISI) in Delhi, offering a full Professorship there, which I accepted.

Though I decided to go back to India, which institution I’d join there took some more time to determine. I had a standing invitation from K.N. Raj at the Delhi School of Economics. Even before I left MIT he asked me to teach a course in MIT’s summer-vacation period. I went and taught part of a course, which had good students (including Amitava Bose, who in his later professional life became close to me, served as a Director of the Indian Institute of Management in Kolkata, and finally lost his long battle against cancer). But I soon found out that the only job Raj could offer me was that of a Readership (Associate Professorship), as a full Professorship was not yet vacant. Amartya-da advised me against accepting a Readership, since in Indian universities there could be ‘many a slip’ even when a Professorship became vacant. I went back to MIT after the vacation, and soon after I got a message from T.N. Srinivasan of the Indian Statistical Institute (ISI) in Delhi, offering a full Professorship there, which I accepted.

I was somewhat familiar with the Kolkata headquarters of ISI, a world-class center for statistics those days, with a leafy campus, but I did not know much about the Planning Unit of ISI in Delhi where I was to work. It did not have a campus at that time, it was originally linked to the Indian Planning Commission, which was housed in a large Government building, called Yojana Bhavan. When P.C. Mahalanobis, the distinguished statistician and founder-director of ISI was a member of the Planning Commission, from 1955 to 1967, he wanted this unit to provide research input to the planning process. By the time I joined ISI Mahalanobis had left the Planning Commission, and this unit turned itself into a general research outfit, though later some teaching of post-graduate students started. It continued being housed in that Government building until a new campus for the Delhi branch of ISI was completed. Read more »

Monday, December 6, 2021

The Demands of Citizenship: JFK at Vanderbilt

But this Nation was not founded solely on the principle of citizens’ rights. Equally important, though too often not discussed, is the citizen’s responsibility. For our privileges can be no greater than our obligations. —John F. Kennedy, May 18, 1963, Nashville

May, 1963. JFK is in a centrifuge, buffeted by a series of challenges from abroad and at home that would have taxed anyone. Underneath the glamour and optimism of Camelot was a roiling mess of seemingly intractable problems, including the global threat of an aggressive, expansive Communism, and domestic unrest related to the irrefutable moral logic of the Civil Rights Movement set against implacable, and often violent, resistance.

All of this, the triumphs and the troubles, are, for the first time, playing out in black and white (and occasionally in living color) on television screens across America. We have clearly moved into a “see it now” age: in just the decade of the 1950s, the percentage of households with sets went from about 9% to about 87%. Soft censorship (reporter circumspection and editorial oversight) still existed, but the vast majority of people were getting their news visually, and sometimes that news contained graphic and unforgettable images.

Kennedy clearly understood the power of the new medium. He wrote a short essay for TV Guide in November 1959, in which he discussed his concerns about television’s potential for demagoguery, but also said it gave an opportunity to the viewing public to judge for itself a candidate’s sincerity—or lack of it. If that was a prediction, it was a pretty good one: Ten months later, in what was a decisive moment in the 1960 election, he was debating Richard Nixon, and winning, in part, on style points. Read more »

What A Way To Go

by Usha Alexander

[This is the fifteenth in a series of essays, On Climate Truth and Fiction, in which I raise questions about environmental distress, the human experience, and storytelling. All the articles in this series can be read here.]

I began writing this series eighteen months ago to explore the human experience and human potential in the face of climate change, through the stories we tell. It’s been a remarkable journey for me as I followed trails of questions through new fields of ideas along entirely unexpected paths of enquiry. New vistas revealed themselves, sometimes perilous, always compelling. And so I went. The more I’ve learned, the more I’ve come to realize that our present environmental predicament is actually far worse off—that is to say, more threatening to near-term human wellbeing and civilizational integrity—than most of us recognize. This journey is changing me. So when I now look at contemporary works of fiction about climate change—so-called cli-fi, which I’d hoped might provide fresh insights—so much of it strikes me as somewhat underwhelming before the task: narrow, shallow, tepid, unimaginative, or even dishonest.

I began writing this series eighteen months ago to explore the human experience and human potential in the face of climate change, through the stories we tell. It’s been a remarkable journey for me as I followed trails of questions through new fields of ideas along entirely unexpected paths of enquiry. New vistas revealed themselves, sometimes perilous, always compelling. And so I went. The more I’ve learned, the more I’ve come to realize that our present environmental predicament is actually far worse off—that is to say, more threatening to near-term human wellbeing and civilizational integrity—than most of us recognize. This journey is changing me. So when I now look at contemporary works of fiction about climate change—so-called cli-fi, which I’d hoped might provide fresh insights—so much of it strikes me as somewhat underwhelming before the task: narrow, shallow, tepid, unimaginative, or even dishonest.

At the same time, a few conclusions have begun to coalesce in my mind. Some of these may seem controversial, largely because they run contrary to the common narratives that anchor our dominant understanding of how the world works—our stories of human exceptionalism, technological magic, and the tenets of capitalist faith. Indeed, many of my own assumptions and worldviews have been challenged, altered, or broken. In their stead, new ways of thinking have taken root, as I began seeing through at least some of our most cherished cultural fabrications to understand our quandary with a different perspective.

Learning these things has been emotionally taxing, but I don’t believe there’s any way forward without a clear-eyed, big-picture view of our planetary and civilizational plight. And so, for better or worse, I wish to sum up my thoughts here, before ending my explorations through this series, which I next expect to turn toward thoughts on how one might respond to it all: hope, despair, expectation, fear, carrying on, looking ahead, finding new stories. I trust there are others out there, who would also rather reckon with what’s happening than go on pretending we needn’t adjust our expectations for the future… although, I confess, there are certainly days when I envy those who are able to go on pretending. What follows isn’t for the faint of heart: Read more »

Monday Poem

A Question of Necessity

“Can you tell me a certain thing

that is a moral fact?” is a

specious question

because the fact of the thing

exists as something essential

to the survival of homo sapiens

in creating civilization, though civilization

does not always live up to the necessity

of its essential thing.(the root

of what it means to be civilized) so the fact

of chaos, or free natural inclination,

becomes the universal mode simply because

morality, being thought subjective, and a

hard taskmaster, cannot be universally defined

and we all become hawks or vultures

feeding on carrion doves. it’s a question

whose answer itself is not an easy act

but is, nevertheless, with or without definition, love,

which is foremost not a thing we feel, but … do:

………………………………………………………………a moral act

…………………………………………………………….. made fact

Jim Culleny

9/13/20

Where shall wisdom be found?

by Jeroen Bouterse

Permanent Crisis

In one of the opening scenes of The Chair (2021), we are treated to an ideal-typical self-diagnosis of a struggling English department. Its new chair, Ji-Yoon Kim, narrates:

I’m not gonna sugarcoat this: we are in dire crisis. Enrollments are down more than 30 percent, our budget is being gutted. It feels like the sea is washing the ground out from under our feet. But in these unprecedented times, we have to prove that what we do in the classroom – modeling critical thinking, stressing the value of empathy – is more important than ever, and has value to the public good. It’s true, we can’t teach our students coding or engineering. What we teach them cannot be quantified, or put down on a resumé as a skill. But let us have pride in what we can offer future generations. We need to remind these young people that knowledge doesn’t just come from spreadsheets or Wiki entries. Hey, I was thinking this morning about our tech-addled culture and how our students are hyperconnected 24 hours a day, and I was reminded of something Harold Bloom wrote. He said: ‘Information is endlessly available to us. Where shall wisdom be found?’

The idea that a humanities department would be experiencing rough times is not a hard sell. The series uses the high-mindedness of this speech to let the silly and petty behavior of the faculty stand out more, but it also leaves little question that Ji-Yoon’s diagnosis is basically right: it is simultaneously extremely hard to defend the value of the humanities in this day and age, and especially important, because they offer something that runs counter to what we tend to believe the tendencies of that day and age to be – instrumentalism, materialism, marketability, et cetera.

Precisely what that value consists of is contested, and generic crisis talk is also a way for the chair not to become too specific – in particular, not to choose sides between the older, canon-oriented generation (the men in the scene nod in relief when Ji-Yoon name-drops Harold Bloom) and the younger, progressive staff. The main point now, however, is that this diagnosis is immediately recognizable: while there are skills that fit comfortably within the modern economy, Ji-Yoon says, the humanities are untimely; they provide a kind of knowledge that our society both needs and undervalues. Read more »

Keeping House

by Michael Abraham-Fiallos

I am a messy person.

I am a messy person, and I don’t like to clean. My house testifies to this: cups in the sink, mail on the counter, books spilling off the windowsills, too much laundry in the bin, a scattering of incense dust on the coffee table alongside burnt out candles and ephemera (an old insurance card, jewelry, more books). About twice a month, I get fed up with myself and obsessively clean the house. Or company comes, and I scramble. But the rest of the time, I subsist in my mess. My psychiatrist thinks this is a matter of motivation, of the depressive side of manic depression. It is less that and more a matter of being a wanderer somewhere else, in a place wet with rain and glistening with wildflowers, in a place where the wind is always whistling, and the sun hangs perpetually low to the horizon, casting its light yellow and fragile past the hills and across the valley. This place is a place in my own head, a space where the eros in me dwells, where my capacity to bring things forth into the world exists, where the grand feelings and the big thoughts are. In the lull of the afternoon, I find myself at my keyboard exploring myself, and I forget to run the washing machine. Or, I take long walks in the daylight to get mired in thought, and the dishes be damned. When my husband arrives home from work, there is so much to tell him, so much to show him, which has been found or made or thought up—which has been brought forth—in the wandering, so much to hear from him that might provoke tomorrow’s wandering (all my best wandering has something to do with my husband).

Maybe what I mean is I’m lazy or perhaps distracted. It’s a cliché about scholars and writers (skola does, after all, mean “leisure”): so wrapped up in their minds that the external world around them fades into the background. In the matter of keeping house, I fit this cliché. However, there is more to keeping house than tidiness.

I have always thought it was a funny phrase: keeping house. What is one keeping? It seems to me that one is keeping something alive, keeping something kindled, as one does a flame with one’s hand. Something precious and vibrant is meant to be kept at the center of the home, as once, not so long ago, the hearth was kept stoked to keep the home warm and habitable. Upon thinking this, I went searching for what this something might be that one keeps alive or open or warm with one’s care and attention, went searching for what it is that makes a house a house. I found the answer, as I always seem to do, in the concept of love, but in a very peculiar and striking account of what love is: what the French feminist philosopher, Luce Irigaray, calls demonic love or sorcerer love. She explicates this concept in an essay titled “L’amour Sorcier: Lecture de Platon, Le Banquet, Discours de Diotime,” rendered in English by Eleanor H. Kuykendall as “Sorcerer Love: A reading of Plato’s Symposium, Diotima’s Speech.” It appears in a volume titled Luce Irigaray in French in 1984, and Kuykendall published her translation in 1989. Read more »

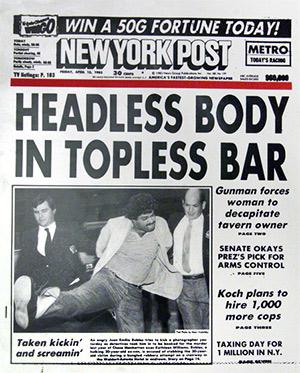

Why Today’s Republicans Hate the New York Times So Much

by Akim Reinhardt

When I was growing up during the 1970s, America still had a vibrant and thriving newspaper culture. My hometown New York City boasted a half-dozen dailies to choose from, plus countless neighborhood newspapers. Me and other kids started reading newspapers in about the 5th grade. Sports sections, comics, and movie listings mostly, but still. By middle school, newspapers were all over the place, and not because teachers foisted them upon us, but because kids picked them up on the way to school and read them.

When I was growing up during the 1970s, America still had a vibrant and thriving newspaper culture. My hometown New York City boasted a half-dozen dailies to choose from, plus countless neighborhood newspapers. Me and other kids started reading newspapers in about the 5th grade. Sports sections, comics, and movie listings mostly, but still. By middle school, newspapers were all over the place, and not because teachers foisted them upon us, but because kids picked them up on the way to school and read them.

Of course when dropping coins at the local newsstands and into boxes, us youngsters typically picked up tabloids such as the New York Post and Daily News, not those fancy papers so big you had to unfold them just to see the entire front page: the New York Times and the indecipherable Wall Street Journal. Those were for adults, and usually white collar ones at that.

My father was blue collar and not a big newspaper reader. But my mother was a high school English teacher and she made a family ritual of going out to buy the massive Sunday Times when it first hit newsstands on Saturday evenings. Mostly she just wanted the Book Review. We’d also pick up a Daily News because they too had a formidable Sunday edition; not cut into sections like the Times, but in a single massive tome like a phonebook. It had the best comics section of any NYC paper. After my sister and I had our way with the News, I’d occasionally thumb through the Times. No comics, but they did have an entire sports section.

As I rambled towards adulthood, I continued buying the tabloids for their local sports coverage and hilarious front page headlines. However, I also found myself reading more of that Sunday Times. Never all of it, of course. I was far too young, and anyway, never trust anyone who does; no one’s interests are really that far ranging. Read more »

Catspeak

by Brooks Riley

The 28th Dress

by Rafaël Newman

Leave plenty of time to stand in line at the gift shop when you visit Einsiedeln Abbey, in the Swiss canton of Schwyz. The Klosterladen, in a courtyard to the right of the 18th-century complex—which is built on the site of the 9th-century hermitage where Saint Meinrad was sustained by the Waldleute, or Forest People—sells inspirational books by religious luminaries past and present, CDs of organ music and Gregorian chants, specialty baked goods, local wines and spirits, and Einsiedler Raben, gianduja-filled pairs of chocolate ravens, as delicious as they are ominous. There are ranks of postcards, inspirational and touristic, holy pictures, incense, and all manner of candles. But the gift shop’s main attraction for pilgrims at the Abbey, long a standard stop on the Way of St. James, are its devotional trinkets: rosaries, amulets, icons, and, in particular, medallions bearing the likeness of a saint or Biblical figure, all kept in black velvet-lined display drawers at the checkout, viewable only with the assistance of the lone cashier. Pilgrims from North America, Eastern Europe, Asia, and across the Catholic world linger reverently over the offerings, oblivious to those behind them, like so many fan girls and boys at Comic-Con; and they leave, bedecked in the gawdy signs of their faith, resembling participants in a cosplay event.

This jarring, strange-making, for believers no doubt sacrilegious impression, of an ancient, global monotheism as modern sci-fi genre, is compounded, as well as mitigated, by a glimpse of the proper object of the pilgrims’ veneration in the Benedictine Abbey’s cathedral church. Under a soaring ceiling adorned with the most gorgeously overwrought productions of counter-reformation Baroque—putti, florets, nativities, trompe-l’œil cameos, all in icing-sugar pinks, blues, and ochres—stands the glittering black marble Chapel of Our Lady, its plain stone bas-relief insets creating a two-tone reproach to the frivolity above. Within the chapel, however, inaccessible behind its wrought-iron grilles but open to view on three sides, the sternness is tempered, like the miraculous transition from black-and-white to Technicolor in The Wizard of Oz, by a further polychrome effusion: Einsiedeln’s celebrated, late Gothic Schwarze Madonna, a foot-and-a-half-tall wooden effigy of Mary, carved out of limewood, its 15th-century paint long since worn away and blackened by soot and smoke. The Black Madonna, holding the infant Jesus in her left hand and a scepter in her right, is suspended on the back wall of the chapel against a golden bas-relief combustion of cloud and rays of holy illumination. She is regularly clad and re-clad, in keeping with the ecclesiastical calendar, in an ever-changing sacred wardrobe of 27 dresses, gorgeously brocaded and complete with all the requisite accessories (as well as a matching outfit for Baby Jesus), each with its own liturgical or geographic appellation: the “Neues Florenzer”, the “Menzinger”, the “Altes Engelweih”, the “Innsbrucker”, one more enchanting than the other. Before the chapel, with the most direct view of the effigy, pews have been erected to allow worshippers to kneel and adore the Virgin. The effect on the outsider to this rite is of a children’s birthday party, whose guests are rapt in admiration of the showpiece gift, the very latest Barbie: Diversity Queen of the Universe™. Read more »

Learning To Listen

by Eric J. Weiner

We find our voice in solitude, and we bring it to public and private conversations that enrich our capacity for self-reflection. Now that circle has been disrupted; there is a crisis in our capacity to be alone and together. But we are in flight from those face-t0-face conversations that enrich our imaginations and shepherd the imagined into the real. There is a crisis in our ability to understand others and be heard. — Sherry Turkle, Reclaiming Conversation

Although there might be nothing wrong with our hearing, we are quickly losing our ability to practice three formative modalities of democratic listening: Mindful, Aesthetic and Critical. These three modalities support our active participation in sustained, intimate conversations where we learn with and from each other. Millennials in particular struggle to listen to their friends, parents, and teachers for more than a few seconds without their brains becoming distracted by the ubiquitous hand of technology.[1] Adding to the distractions of technology, both adults and children, when in dialogue, confuse waiting for their turn to talk with the practice of democratic listening. Although we are hardwired for grammar;[2] cognitively mapped to construct, comprehend, and interpret meanings that arise from the soundscapes of language, culture and history; and can distinguish sound patterns, dissonances, silences, and noises in the ether,[3] the brain listens only to what the mind is prepared to hear.[4]

Although there might be nothing wrong with our hearing, we are quickly losing our ability to practice three formative modalities of democratic listening: Mindful, Aesthetic and Critical. These three modalities support our active participation in sustained, intimate conversations where we learn with and from each other. Millennials in particular struggle to listen to their friends, parents, and teachers for more than a few seconds without their brains becoming distracted by the ubiquitous hand of technology.[1] Adding to the distractions of technology, both adults and children, when in dialogue, confuse waiting for their turn to talk with the practice of democratic listening. Although we are hardwired for grammar;[2] cognitively mapped to construct, comprehend, and interpret meanings that arise from the soundscapes of language, culture and history; and can distinguish sound patterns, dissonances, silences, and noises in the ether,[3] the brain listens only to what the mind is prepared to hear.[4]

In our current historical conjuncture, the mind is not prepared nor is it being prepared to hear the pangs of hunger in the discourse of poverty; the terrorizing memories of male violence and sexual assault from the mother-tongue of surviving women; the anxieties of dis-ease and economic insecurity in the angry and disillusioned voices of youth; the brutality of homelessness in the quiet drawings of children who sleep in cars and shelters; the academic discourse of white supremacy deeply embedded within the sterilized language of meritocracy; the communality of working-class culture splattered in blood, sweat, and country; the groan of disability pushing against the structural forces of ableism; the tongue-tying of identity within sequestered spaces of difference; the diverse voices of radical love driving the outrage against fascist machineries of death; the intubated wheezing of dying democracies; the hushed courage of LGBTQ+ people navigating the heteronormative and cis-gendered architecture of everyday life; and the incessant white noise of power burying the refrain of negative freedom in the hook of capitalist opportunity. That which the mind is not prepared to hear negates our capacity to listen and understand, to learn from those most in need, and to be mindful, aesthetically sensitive, and critically awake to the radical possibilities that arise out of deep and meaningful conversation.

From this perspective, democratic listening, like its genetic siblings literacy and learning, should be understood as a social practice. Read more »

The education innovation dilemma

by Sarah Firisen

Many years ago, I returned to my old high school for a visit with friends who were classmates back in the ’80s. Exploring the school and marveling over what had changed and what remained exactly the same, we ventured into the language lab. The room smelled exactly the same as it had in 1983, and it took me right back to those days of incredibly boring language lessons and sitting in that room with headphones on repeating monotonous phrases.

Many years ago, I returned to my old high school for a visit with friends who were classmates back in the ’80s. Exploring the school and marveling over what had changed and what remained exactly the same, we ventured into the language lab. The room smelled exactly the same as it had in 1983, and it took me right back to those days of incredibly boring language lessons and sitting in that room with headphones on repeating monotonous phrases.

I took French for seven years in middle and high school, Latin for five, and German for two. Language classes were always my educational Achilles heel. Those seven years enabled me to speak the most halting, grammatically painful, badly accented French when we visited on vacation, and I’ve always wished I spoke it better.

I’m now planning to visit Paris in January with my daughters, Sasha, 18, Anya, 21, and Anya’s boyfriend, Liam. Growing up in the U.S., they all learned Spanish in school rather than the de rigor in the UK, French. My daughters never showed much more linguistic aptitude than I did in school. In preparation for our trip, Anya suggested that we all download Duolingo, a language learning app. Read more »

Monday Photo

On the Road: Among the non-Humans

by Bill Murray

Cogito Ergo Sum? Welcome to the party. There’s a lot more going on out there than we sometimes think: Cephalopods memorize, learn, invent, and play; indeed, they acquire information about the outside world while still in their eggs. • The small, flowering thale, or mouse-ear cress, can detect the vibrations caused by caterpillars munching on it and so release oils and chemicals to repel the insects. • The fruit fly Drosophila shows evidence of depression if it gets too hot. • Plants discern the difference between blue and red light, and use this information to know which direction to grow. They differentiate between the dimming scarlet light of sunset and the brightening orange light of sunrise, to determine when to flower. • Pigs comprehend symbolic language, plan for the future and discern the intentions of others. They bore easily and show a clear preference for novelty. • When researchers arranged oat flakes in the geographical pattern of cities around Tokyo, slime mold constructed nutrient channeling tubes that closely mimicked Tokyo’s metro rail. • Some plants can feel you touching them. • Cuvier’s beaked whales can dive to 10,000 feet and stay there, at tremendous pressure, for up to two hours. In 2020 scientists recorded a Cuvier’s beaked whale staying below the water for 3 hours 42 minutes. • The nearly blind star-nosed mole, the world’s fastest eater, can find and gobble down an insect or worm in a quarter of a second. It hunts by bopping its star against the soil as quickly as possible, touching 10 or 12 different places in a single second. • The 10 centimeter long cleaner wrasse, a reef fish, has joined great apes, bottlenose dolphins, killer whales, Eurasian magpies and a particular Asian elephant in exhibiting self-awareness. Read more »

Cogito Ergo Sum? Welcome to the party. There’s a lot more going on out there than we sometimes think: Cephalopods memorize, learn, invent, and play; indeed, they acquire information about the outside world while still in their eggs. • The small, flowering thale, or mouse-ear cress, can detect the vibrations caused by caterpillars munching on it and so release oils and chemicals to repel the insects. • The fruit fly Drosophila shows evidence of depression if it gets too hot. • Plants discern the difference between blue and red light, and use this information to know which direction to grow. They differentiate between the dimming scarlet light of sunset and the brightening orange light of sunrise, to determine when to flower. • Pigs comprehend symbolic language, plan for the future and discern the intentions of others. They bore easily and show a clear preference for novelty. • When researchers arranged oat flakes in the geographical pattern of cities around Tokyo, slime mold constructed nutrient channeling tubes that closely mimicked Tokyo’s metro rail. • Some plants can feel you touching them. • Cuvier’s beaked whales can dive to 10,000 feet and stay there, at tremendous pressure, for up to two hours. In 2020 scientists recorded a Cuvier’s beaked whale staying below the water for 3 hours 42 minutes. • The nearly blind star-nosed mole, the world’s fastest eater, can find and gobble down an insect or worm in a quarter of a second. It hunts by bopping its star against the soil as quickly as possible, touching 10 or 12 different places in a single second. • The 10 centimeter long cleaner wrasse, a reef fish, has joined great apes, bottlenose dolphins, killer whales, Eurasian magpies and a particular Asian elephant in exhibiting self-awareness. Read more »

Sonic Transportation: It shook me, the light!

by Bill Benzon

ASC, “altered states of consciousness” – I don’t know when the term was first coined, but I became aware of it late in the 1960s. I took it as referring primarily to states of mind induced by psychoactive drugs, such as marijuana, mescaline, and LSD, and to states induced by meditative practice. It presupposes “ordinary consciousness,” which is hardly a single thing when you consider that one can ordinarily be daydreaming, working a math problem, eating a meal, perhaps a good meal, perhaps one that is merely tolerable, hiking in the woods, and so forth, for a long and various list of activities, all of them ordinary.

Music is one of those activities, one I treasure a great deal. I my experience states of musical consciousness can be quite various, some tending toward the ordinary other rather extraordinary. When I was eleven or twelve I read the this is Jean-Baptiste Arban’s Complete Conservatory Method for Trumpet, originally published in mid-nineteenth century France, and variously edited and reprinted since then. Arban is expressing his hopes for the instrument:

There are other things of so elevated and subtle a nature that neither speech nor writing can clearly explain them. They are felt, they are conceived, but they are not to be explained; and yet these things constitute the elevated style, the grande ecole, which it is my ambition to institute for the cornet, even as they already exist for singing and the various kinds of instruments.

What was he talking about? What does he mean by “grande ecole”? I doubt that I sought out an English translation. Whatever it was, it seemed important, albeit mysterious. Perhaps even, important because mysterious.

Does this grande ecole involve an altered state of consciousness?

Rock and Roll

During the early 1970s, while I was working on a master’s degree at Johns Hopkins in Baltimore, I played with a rock band called St. Matthew Passion. We modeled ourselves on Blood, Sweat, and Tears and on Chicago, bands that blended elements of jazz with rock. Thus, in addition to a four-piece rhythm section (guitar, bass, keyboards, drums) we had three horns: sax, trumpet (me), and trombone. Read more »