by Tamuira Reid

The left is now rationing life-saving therapeutics based on race, discriminating against and denigrating, just denigrating white people to determine who lives and who dies. In fact, in New York state, if you’re white, you have to go to the back of the line to get medical help. If you’re white, you go right to the back of the line. —Donald Trump, January 2022

*In Memory of Neema J. (1945- 2020)

One

Neema could sing. Really sing. Thick songs with smooth edges, full of blood memory and knowing. I pressed my ear against the floorboards of our new apartment, the one we would shelter in during the height of a pandemic we didn’t know was coming. In-between moving boxes and piles of books, I lay listening, pressing my palms flat to the ground. The steam pipes rattling alive with each husky note.

Neema was also crazy, people in the building would tell me, in hushed, apologetic tones. “Not right in the head.” “Not all there.” “Gone.”

“Dementia,” the Super said flatly, after I called him in the middle of the night, called about the smell of something burning beneath me, one floor down. The smell of a slow burn, a deep burn. A castiron skillet left unattended for hours burn. Neema’s mind had become a slippery slope where important details often fell to the wayside.

Singing never left her, even as her mind closed shop. Songs took root like trees in her belly.

I learned if I turned the lights off, I could hear her better. Read more »

From the gatherings at Ashis Nandy’s home, and particularly from my numerous discussions with him I learned to think a bit more carefully about three major social concerns in India.

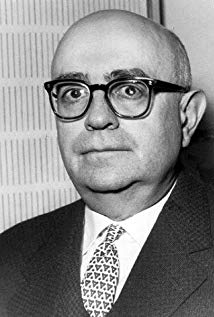

From the gatherings at Ashis Nandy’s home, and particularly from my numerous discussions with him I learned to think a bit more carefully about three major social concerns in India. The philosopher Theodore Adorno, probably with activities such as reading serious literature and listening to classical music in mind, famously said about himself:

The philosopher Theodore Adorno, probably with activities such as reading serious literature and listening to classical music in mind, famously said about himself:

Sughra Raza. Bey Unvaan. Anza-Borrego Desert Park, Calfornia, 2017.

Sughra Raza. Bey Unvaan. Anza-Borrego Desert Park, Calfornia, 2017.

“Sewer designs… For me, it took about a year to exhaust my fascination with the underground maze of waste. That’s when I realized the single most important point to grasp about designing sewer lines is that the shit must flow downhill. That’s all one needs to know. Nothing else matters.” So muses Emma, a smart young sewer engineer and the protagonist of Sara Goudarzi’s debut novel The Almond in the Apricot. The book takes us through the convoluted maze of Emma’s own inner turmoil that begins to blur the boundaries between her physical world and her dreams.

“Sewer designs… For me, it took about a year to exhaust my fascination with the underground maze of waste. That’s when I realized the single most important point to grasp about designing sewer lines is that the shit must flow downhill. That’s all one needs to know. Nothing else matters.” So muses Emma, a smart young sewer engineer and the protagonist of Sara Goudarzi’s debut novel The Almond in the Apricot. The book takes us through the convoluted maze of Emma’s own inner turmoil that begins to blur the boundaries between her physical world and her dreams. When I am not doing well in my own head, I turn to the tarot. While no substitute for therapy or psychiatry, the tarot has an ancient function that is symbiotic with these modern methods for coping with the wild unruliness of the mind. I know it sounds silly. But before there was psychology and medicine, there was magic, and that is not silly at all. People crave rituals and symbols; they crave narratives about themselves with which to play and to experiment. And the tarot is nothing if not an arcane form of play and experimentation with the idea of the self, packed with ritual and narrative and symbol. Magic, you see, is a very minor thing. It does not make great things happen, and, when it is practiced honestly and forthrightly, it does not claim to make great things happen. Instead, magic is meant to open up little moments, little apertures into self-understanding, that allow for the flourishing of subjects in an otherwise mean and obscure world. It is difficult to be a subject in the world; it is a task with no guidebook and with few obvious parameters. Little practices that seek after the integration of the self with the world, that seek to make distinct and clear not only who the self is but what the self means and is capable of accomplishing and being with the materials of the world at hand—these kinds of practices, which include both the tarot and psychotherapy (the latter being perhaps a practice of magic in our modern lives), make it

When I am not doing well in my own head, I turn to the tarot. While no substitute for therapy or psychiatry, the tarot has an ancient function that is symbiotic with these modern methods for coping with the wild unruliness of the mind. I know it sounds silly. But before there was psychology and medicine, there was magic, and that is not silly at all. People crave rituals and symbols; they crave narratives about themselves with which to play and to experiment. And the tarot is nothing if not an arcane form of play and experimentation with the idea of the self, packed with ritual and narrative and symbol. Magic, you see, is a very minor thing. It does not make great things happen, and, when it is practiced honestly and forthrightly, it does not claim to make great things happen. Instead, magic is meant to open up little moments, little apertures into self-understanding, that allow for the flourishing of subjects in an otherwise mean and obscure world. It is difficult to be a subject in the world; it is a task with no guidebook and with few obvious parameters. Little practices that seek after the integration of the self with the world, that seek to make distinct and clear not only who the self is but what the self means and is capable of accomplishing and being with the materials of the world at hand—these kinds of practices, which include both the tarot and psychotherapy (the latter being perhaps a practice of magic in our modern lives), make it

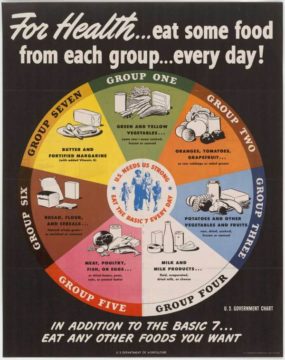

What to eat? A seemingly simple question, but one that has become increasingly difficult to answer. And why is that? My initial hypothesis is that as modern society becomes more and more distanced from traditional and local cuisines, people have less guidance as to what to eat; this puts increased pressure on individuals to make a conscious choice, but with unclear and often conflicting information about how to make this choice. In other words, people used to just eat whatever their grandparents had eaten, and this worked relatively well. Now, with an overabundance of choice and ignorance of one’s own past, we are lost, wandering through the supermarket aisles like a traveler lost in the woods. Thus, we see diets, meal plans, food delivery apps, and a myriad of other things jump in to fill the void that has been abdicated by family and community. But this story is perhaps so obvious that it does not need retelling. It is, after all, the story of the modern, global world. Nevertheless, it’s useful to pause, look around, and ask ourselves, “How did we get here? What is this place?” Let me sketch a few examples of people attempting to answer our initial question, “What to eat?” to help illustrate our general predicament.

What to eat? A seemingly simple question, but one that has become increasingly difficult to answer. And why is that? My initial hypothesis is that as modern society becomes more and more distanced from traditional and local cuisines, people have less guidance as to what to eat; this puts increased pressure on individuals to make a conscious choice, but with unclear and often conflicting information about how to make this choice. In other words, people used to just eat whatever their grandparents had eaten, and this worked relatively well. Now, with an overabundance of choice and ignorance of one’s own past, we are lost, wandering through the supermarket aisles like a traveler lost in the woods. Thus, we see diets, meal plans, food delivery apps, and a myriad of other things jump in to fill the void that has been abdicated by family and community. But this story is perhaps so obvious that it does not need retelling. It is, after all, the story of the modern, global world. Nevertheless, it’s useful to pause, look around, and ask ourselves, “How did we get here? What is this place?” Let me sketch a few examples of people attempting to answer our initial question, “What to eat?” to help illustrate our general predicament. I come to praise bakeries past and present. And older men and women faithfully carrying out their duties to their grandchildren.

I come to praise bakeries past and present. And older men and women faithfully carrying out their duties to their grandchildren. Was it inevitable, this ongoing anthropogenic, global mass-extinction? Do mass destruction, carelessness, and hubris characterize the only way human societies know how to be in the world? It may seem true today but we know that it wasn’t always so. Early human societies in Africa—and many later ones around the world—lived without destroying their environments for long millennia. We tend to write off the vast period before modern humans left Africa as a time when “nothing much was happening” in the human story. But a great deal was actually happening: people explored, discovered, invented, and made decisions about how to live, what to eat, how to relate to each other; they observed and learned from the intricate and changing life around them. From this they fashioned sense and meaning, creative mythologies, art and humor, social institutions and traditions, tools and systems of knowledge. Yet it’s almost as though, if people aren’t busily depleting or destroying their local environments, we regard them as doing nothing.

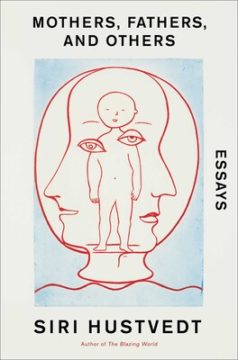

Was it inevitable, this ongoing anthropogenic, global mass-extinction? Do mass destruction, carelessness, and hubris characterize the only way human societies know how to be in the world? It may seem true today but we know that it wasn’t always so. Early human societies in Africa—and many later ones around the world—lived without destroying their environments for long millennia. We tend to write off the vast period before modern humans left Africa as a time when “nothing much was happening” in the human story. But a great deal was actually happening: people explored, discovered, invented, and made decisions about how to live, what to eat, how to relate to each other; they observed and learned from the intricate and changing life around them. From this they fashioned sense and meaning, creative mythologies, art and humor, social institutions and traditions, tools and systems of knowledge. Yet it’s almost as though, if people aren’t busily depleting or destroying their local environments, we regard them as doing nothing. The theme of home—as a topic, question—is woven throughout Siri Hustvedt’s excellent new essay collection,

The theme of home—as a topic, question—is woven throughout Siri Hustvedt’s excellent new essay collection,  Sughra Raza. Inside Out, Boston, 2021.

Sughra Raza. Inside Out, Boston, 2021.