by Bill Murray

If you’d like to start at the beginning, read Part One here.

If you’d like to start at the beginning, read Part One here.

On a piercing-bright, dripping-humid Irrawaddy delta morning in the 1990s, wild, screeching fowl wheeled over trucks full of boys in Chinese dragonheads banging on the side panels, driving in circles, celebrating the new year. The year of the pig had just begun.

The Yangon – Thalyin bridge was three two-and-a-half kilometer, Chinese-built lanes, one in each direction with a rail track separating them in the middle. Having just one lane on a bridge doesn’t keep anybody from passing, of course.

From China all the way around southeast Asia to here, the technique for driving is the same: If you get out around the car in front of you fast enough, you present the oncoming drivers with a fait accompli: I am tying up the entire highway in front of you, so you have no choice but to brake and let me merge in front of the guy beside me.

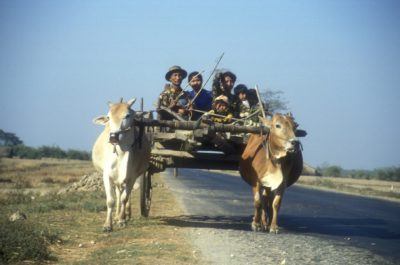

Naturally the oncoming traffic plots to do the same, and tranquility seldom reigns. Yet in the middle of it all, whole Burmese families plodded by on ox carts or old blue Ford or Dodge “buscars” with men and boys stuffed everywhere inside, standing hanging on the back and a dozen more piled on top. Invariably they all broke into wide smiles and waved madly as they wheezed past.

A grizzled brown paddy man walked muddy out of a yellow field to trade some greens (“grass for soup”) and two watermelons for a Lucky Strike. Here our guide, a young man named Chan, showed us “brick factory,” “rice factory” and “vegetable factory.”

While Myanmar was relatively open in the 1990s, it was nevertheless a place that really didn’t work too well. Neglected by its rulers and everybody else, Myanmar was a backwater – a bustling little backwater, true enough, but just where was it bustling off to? For starters, the opposite side of the road.

You drove on the left side of the road, always had, until on 6 December, 1970, they changed driving to the right. Why? Even now, no one is sure. Just about all cars had steering wheels on the right side. Suddenly the driver’s seat had better views of the curb than of oncoming traffic. Now, one day to the next, buses dumped their passengers directly into the middle of the road.

Could it be the leadership woke up insecure one day, was it no more than that? General Ne Win ruled Burma back then, and he, like lots of Burmese, was a keen numerologist. Might Ne Win have found something auspicious in the date 6 December for the driving-side change? Listen, don’t rule it out. Between 1985 and 1987 the Union of Burma Bank issued 15, 35, 45, 75 and 90 kyat notes. About those 45s and 90s: Ne Win’s favorite number was nine.

Or maybe they swapped driving sides because “(a)fter visiting a number of foreign countries, the general observed that most nations drive on the right and proposed that Myanmar follow suit because the country would have to connect to international road networks in the future.”

Or maybe they swapped driving sides because “(a)fter visiting a number of foreign countries, the general observed that most nations drive on the right and proposed that Myanmar follow suit because the country would have to connect to international road networks in the future.”

Indeed, Ne Win traveled a lot. He visited the United States, in 1966. The way I read it, President Johnson sort of stared at him blankly at an initial meeting, and then Ne Win spent the rest of his state visit playing golf in Maui.

He saw a therapist in Vienna. Back home he banned beauty pageants and horse racing. Ne Win resigned abruptly in 1988, admitting his socialist revolution was a failure and spawning democracy demonstrations that led to a crackdown that led in turn to hundreds of deaths.

Putting down what became known as the 8.8.88 student uprising gave birth to the State Law and Order Restoration Council, called the SLORC, a junta that sounded more like a swamp creature too ghastly ever to have been born. Pity its Marketing Director. (While alive, the SLORC, not so good at naming things, also changed the country’s name from Burma to Myanmar.)

We saw in part one how the 8.8.88 uprising birthed the National League for Democracy, and Aung San Suu Kyi’s role as its mediagenic front person. Long run by gray military men presiding over years of stagnant isolation (similar to but without quite the autarkic malevolence of North Korea’s Kims) Burma badly needed a fresh breeze.

Aung San Suu Kyi burst onto that scene. She was fresh. There was also the suggestion that surely, had it not been for her father Aung San’s martyrdom, the intervening forty years of military governments and Ne Win’s dreary “Burmese Way to Socialism” could have been very different.

Aung San Suu Kyi’s 76th birthday was this past weekend. After incarceration since February and pending the conclusion of her trial now underway, she is liable to spend the rest of her life in jail. She will be thinking hard on whether it was all worth it. Worth it to spend 15 years under house arrest. Worth it to miss a great deal of her sons’ lives and the death of her husband in England. Worth it not to manage to follow in her father’s footsteps after all.

Which is not to say her father Aung San lived the dream. His efforts, after all, left him dead. And when Aung San, the father of independent Burma, was shot dead in 1947 the country fell back into the civil war that continues today.

Leading Burma to independence demanded from Aung San a moral adaptability that yielded a colorful life. He started out smuggling himself onto a Norwegian cargo ship in 1940 bound for China. He trained in Tokyo with the Imperial Japanese Army to help snatch away Britain’s empire in the east. He learned Japanese; he went full Fascist.

He would countenance “no nonsense of individualism. He resolved that “everyone must submit to the state….” He wore a kimono, took a Japanese name, trained on Japanese-controlled Hainan island, saluted the Japanese flag and learned Japanese patriotic songs (along with his comrade Ne Win). He strode through mighty crooked insurrectionist timbers. Which is not a moral judgment. Maybe there’s no other kind of insurrectionist.

When his shock troops moved to Bangkok his Japanese Colonel exhorted them to “move ahead of the emperor’s forces” and “lead the fight for Burmese independence.” He was to foment internal rebellion. The Burmese Independence Army fought their way in from the east and “started daily executions of (ethnic) Karens suspected of disloyalty” in which perhaps hundreds of his countrymen were murdered.

The Japanese anointed another soldier, Ba Maw, as figurehead and Aung San became Minister for War. Not getting the top job was a huge break for Aung San’s short career, because soon enough, opinion of the occupying Japanese soured as summary trials, sex slaves, torture, everything bad endured. Ba Maw stayed loyal to the Japanese while Aung San, Ne Win and others tacked back toward Burmese independence. Another ideological pirouette.

By the time the Japanese were defeated Aung San stood for the sovereignty of a new nation. When his interim Executive Council met on the morning of 19 July, 1947, three armed men in military fatigues stormed the chamber killing many, including Aung San. Before long, with a featureless bureaucratic leadership in dire lack of Aung San’s charisma, Burma fell back into today’s continuing civil war. No government has controlled all of Burma since the Brits in 1941.

•••••

Television was introduced in 1979, on one channel, for a few hours a day. In 1995 Myanmar TV still comprised just one station, nothing else on the dial. It broadcast a few hours in the evening, a few in the morning, too, and on weekends. Here’s the schedule for Friday, 10 February, 1995, from the daily paper:

5:00 pm

1. Martial music

5:20 pm

2. Disco Rally

5:40 pm

3. Songs of National Races

6:00 pm

4. Traditional Food of National Races

(Domestic Training School)

(Rakhine)

6:15 pm

5. Songs of Yester Year

7:00 pm

6. Children’s programme

7:15 pm

7. Programme honouring the 48th Anniversary of the Union Day

7:30 pm

8. Agricultural Force – Country’s Development

7:40 pm

9. Programme honouring the 48th Anniversary of the Union Day 7:45 pm

10. Beauty of the State, Dances of the State

7:50 pm

11. Songs in honour of the National Convention

8:00 pm

12. News

13. (something in Burmese – ?)

14. International news

15. National news

16. Weather report

17. Programme honouring the 48th Anniversary of the Union Day

18. The next day’s programme

Hotel TV had cable. In the morning the BBC reported that Burma had released 20 NLD political prisoners. Our new friend Kyaw said it wasn’t on Myanmar TV, but that wasn’t surprising, since SLORC denied holding political prisoners at all.

This was the Strand Hotel, bought and renovated by international investors in a tentative liberalizing after the 1988 uprising, and it was a fine hotel. Lunch for example was served in a sort of chaperoned separation from the hardscrabble of the street, amidst wicker, ceiling fans, 20 foot wood beam ceilings, warmed nuts and Heinekens, accompanied by a badala, the traditional Burmese xylophone made of wood tiles strung along a frame of polished wood. In this case, played by a gap-toothed and grinning older gentleman.

•••••

At Kyauk Tan village you hopped a little wooden dinghy over to a floating pagoda that they said had never flooded, proof of an auspicious Buddha. People made pilgrimages here for their “economy,” or financial health.

At Kyauk Tan village you hopped a little wooden dinghy over to a floating pagoda that they said had never flooded, proof of an auspicious Buddha. People made pilgrimages here for their “economy,” or financial health.

There were these three rocks on stools, see, and if you picked up the green one on the right and it felt light, that was auspicious for your economy. It felt pretty light to me, which was good, because we were going to need some auspicious economy when we got home.

A vivid belief in spirits thrives in Myanmar. Kyaw gave a go at explaining the curious mix of animism and Buddhism. Banyan trees, for example, are known to have spirits. Wherever you find a banyan tree, chances are you’ll find a spirit house underneath it, a little wood box for bananas or pomilons or some other spirit offering.

So what happens if there’s a banyan tree at a pagoda? No problem. You get a spirit house in the middle of Buddha’s house. No conflict. Both belief systems are intertwined.

The other day we stopped to see a particular banyan tree on the Bago road, just before the British cemetery. The shamans under this tree blessed cars. New car owners moved their cars forward and back three times to bow to the car spirit in the banyan tree. Some stopped to get a little insurance blessing each time they drove by. And who knows? Remember, in part one, we hadn’t stopped and not an hour later we didn’t have a windshield.

What a panoply of theologies, beliefs, myths in Burma! Indigenous people called the Wa live in northern Shan state up along the Chinese border, an animist group whose creation story is, they have been in the Wa hills since the beginning of time and evolved from tadpoles. Early British explorers, many of them missionaries, described them as headhunters with a proper headhunting season stretching from March through the last week of April. Their dress in warm weather, wrote James George Scott in Gazeteer of Upper Burma and the Shan States, was nothing at all.

•••••

Down at the water’s edge beside the Floating Pagoda, lazy catfish jostled one another for food the kids threw into the water. We took a spin out around the river, then a walk around Kyauk Tan village.

Someone sold atrocious dried fish from a table. At the end of the street, a house served as the town theatre, screening Burmese videos twice a day, five kyats. The people out here in the country liked Burmese tear jerkers, Kyaw said. In the big city smuggled videos from Thailand were currently the rage. Kyaw reckoned they came over concealed amid legal goods in trucks. They were strictly illegal. The government sanctioned only good ol’ Burmese entertainment.

On videotapes smuggled into Burma you didn’t get subtitles. That’s why Chuck Norris and Rambo were big. It has to be action when you don’t understand the words.

A guy made tin pots by an ancient method involving spinning a wheel that entirely eluded me. One girl just stopped dead in her tracks and stared at us, holding a watermelon slice from the tray on her head. Machines ground sugar cane into a sugary drink.

We drove over to the dock. Chan bought some betel in a ferry waiting room. The betel leaf in Burma is green, wide and round. They slathered it with paste and sprinkled a few betel nut pieces on top. The paste and nuts are bitter. They provide calcium. The leaf is a mild amphetamine.

You could buy branches too, inside of which nestled some kind of larvae. Yep, you bought the branch, plucked the thing out and popped it in your mouth. Tasted like butter, Kyaw said, except crunchy. This was more of a Chinese practice than a Burmese one, he assured us, and he’d only tried it once.

•••••

In 1995, in the main hall of the international airport assembly area were five wall clocks. It was a quarter of six in Hong Kong, a quarter of six in Singapore, a quarter of five in Bangkok, a quarter of ten GMT – and four fifteen in Burma.

Jammed thick onto the viewing platform, families craned and waved at kin walking up the Silk Air ramp, Singapore bound, probably on the first flight of their lives, craning and waving madly back.

Poignant. You couldn’t really afford to fly if you were common folk and we couldn’t help but think they had saved and saved for those tickets, and maybe the fervent waves were because some of those folks weren’t coming back.