by Thomas Larson

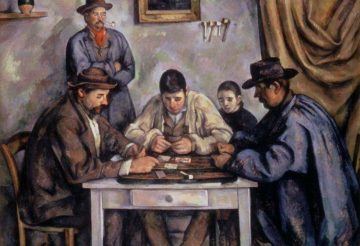

Not long ago, in Philadelphia’s Barnes’ Foundation, I stood close enough to touch Paul Cezanne’s monumental, “The Card Players.” I was mesmerized how paint, texture, composition, and pose achieve an almost granitic-like intensity—three burly men around a table, cards in hands, another man holding a pipe and looking on, and a fifth, a feminine boy, his eyes downcast, echoing and softening the self-absorption of the men before him. The standing man and boy are witnessing the huddle of the three; the two standing invite us to witness the subject and its witnesses, a triangulation of viewer, inner viewers, and inner seen. A painting with its audience internally present and, thus, externally implied.

This canvas, from Cezanne’s final period in the 1890s, is the fifth and most complicated of the paintings he composed of this men-playing-cards motif. Four other “Card Players” were done between 1890 and 1895, all smaller and with fewer figures than this one in the Barnes, measuring 4.5 x 6 feet—but feeling much larger. The figures, who sat for many sketches, are Provence farmhands; the game they appear to be playing is gin rummy, for fun, it seems. No bets are on the table. One critic has called the Barnes painting, a “human still life,” in homage to Cezanne’s love of discovering form and shape with color and palette knife, recognizable as his tilty sensibility when painting fruit on tables and tablecloths in kitchens. He leaves narrative behind in most of these time-stolid works, though the great Barnes’s “The Card Players” with its five massive figures to me does sketch a mysterious tale.

The café wall is stanched with a pipe rack (study closely the formal triangulation of pipes from wall to man to table) and a single drawn side-curtain, the scene a tomb-like abode, a heaven but not forever, its inhabitants, there, past work, but also overtime for a purpose, perhaps clearer to them than to us: to stay ungrudgingly. For the painter. For Cezanne to stage and capture. So that as with his many transcendent final canvases—some taking years to finish or are left unfinished, which we, those who behold their majesty, stare at and fail to imagine what is undone—he could paint this immutable solidity of the evanescent I find before me.

It’s not only his subjects huddled there, soul-solid, before him, sitting for hours, perhaps, over many days, the heat in those cloaks, the withdrawal into themselves in their gazes at their “hands,” an absorption to the art of keeping still and to this painting’s eventual afterlife. It is also Cezanne enacting a painting by Cezanne—no one having anything better to do than to let the artist work on the piece toward its version, its unfinishment—perhaps the truer subject on display, us witnessing a game of cards in life stilled. (John Updike: “Pollock painting is the subject of Pollock’s paintings.”) That largesse of the café scene in Aix-en-Provence is proof of the painting’s battleship solidity. Time has stalled. The work cannot sink; that’s how heavily present it is. There is no woman or child calling from the street, no sundown hurrying the men to drinks or to dinner or to sleep, no nada-loving patrons or glances from waitress or cook or barkeep affixing the scene in their memories.

Cezanne paints the ongoing moment to suggest/embody its immobility as its temporality. In other words, its moment is so densely inescapable that the moment feels lengthened, closer to an eternal present and farther from the rough action (a soccer ball going into a goal or a bullet leaving its chamber for the head of a wincing North Vietnamese soldier). The burdensomeness of the cloaks in the midst of the game imply they are sitting there still, to this day, a kind of nailed-to-the-cross permanence. The day they are painted is our day as well. Indeed, for them no evening is passing, no night is coming on. Their supper’s been eaten, and the cooks are cleaning up, and the barkeep is behind us, reading the paper. The four men and a boy (it seems this intransigence is what the lad has to look forward to) are rather incapable of being outside the painting.

Of course, paintings frieze the conditional state. But this one has unassailable inertia. It is an ode to the blocky, to the clumped, to the “we shall not be moved”: sealed up or sealed in. Who can say? Tightest of all its enigmas is its secretive core, the card game. Each of the three holds a good hand, a pat hand, a lousy hand, stalled halfway from betting on what will be and what will be. Bet/bluff, one up/stand pat, give away nothing. Each looks at his cards, as if looking up would give away his bluff or his fact. Eyes on the cards further stabilizes the mystery.

Moreover, the human position Cezanne arrests is conditional chance, biding its time, the consequence as yet unfallen one way instead of another. “It could have been otherwise,” the poet Jane Kenyon wrote. Take your pick. One of the men will sicken with disease. Another will be lucky in love. Still another—whose wife is readying to leave him that very night—will cry himself to sleep. Not yet, though, for it is much more critical that we are preserved in the moment of what will be where the painting reminds us we know full well what we don’t know.