by Peter Wells

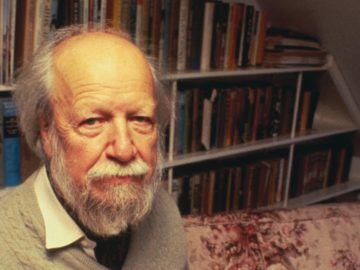

Seventy years ago, according to William Golding: The Man Who Wrote Lord of the Flies (Carey, 2009), the future Nobel prizewinner was a middle-aged English teacher in a private boys’ school in Salisbury, UK, and not enjoying it. He had written three novels, none of them published, though some of his poems had gone into print. His novel about schoolboys killing each other on a tropical island, originally entitled Strangers From Within, was begun in 1951 and first sent to a publisher in 1952. It was rejected by seven publishers before Golding sent it to Faber & Faber in 1953, where the reader, Polly Perkins, pronounced it:

An absurd and uninteresting fantasy about the explosion of an atomic bomb on the colonies and a group of children who land in the jungle near New Guinea. Rubbish and dull. Pointless.

Golding might have continued for a further twenty years in the job he hated, had not a new member of the Faber & Faber team, Charles Monteith, picked up the well-thumbed manuscript from the reject pile and taken it home. Should we be grateful to him?

Synopsis

Lord of the Flies (published 1954) tells the story of a group of twenty-odd English schoolboys, aged between five and twelve, who are stranded on a coral island while being evacuated from England during a global nuclear war. Their plane was shot down, the passenger pod was ejected, and their adult supervisors (and probably an unknown number of children) did not survive. Ralph (handsome, fair-haired, naval officer’s son) and Piggy (fat, bespectacled, intelligent boy with a vulgar accent), the first two boys to appear, call the other boys to a meeting by blowing on a conch shell. Apart from a group of cathedral choristers, most of the boys are strangers to each other. Ralph is elected chief, and Jack, the masterful leader of the choir, is put in charge of hunting (for there are pigs on the island, as well as fruit). Ralph decrees that a signal fire must be lit, and Piggy’s spectacles are used to light it. The boys stoke the blaze over-enthusiastically, causing a wildfire in which a ‘littlun’ [small boy] dies.

Although Ralph tries to make the boys concentrate on building shelters and keeping the signal fire going, most of them prefer to play or hunt. While the hunters are killing their first pig, a ship passes, but the fire has gone out. This causes an argument, during which Piggy is attacked by Jack, and his spectacles are partially broken. At the ensuing meeting it is revealed that some of the boys are scared of a ‘Beast.’

Shortly afterwards, there is an air battle over the island and a dead airman falls by parachute on to the hill where the signal fire is situated. The corpse, in flying gear and goggles, and still attached to the parachute, terrifies the boys who see it in semi-darkness, and they are convinced it is the ‘Beast.’

Jack forms a tribe in opposition to Ralph; they kill a pig, and develop a rite involving putting its head on a stake to placate the Beast. Simon, a sensitive member of the choir, who suffers from epilepsy, has a terrifying mystical experience watching the head, which is covered in flies. (It is the ‘Lord of the Flies.’) Later, Simon finds the airman, and realises that the ‘Beast’ is just a dead human being. Running back to inform the others, who are already re-enacting the killing of a pig in a “demented” dance, he is killed in an orgiastic frenzy by all the boys (including Ralph and Piggy), who are panicked into thinking that he is the beast.

The next morning Jack and his followers attack Ralph’s group and steal Piggy’s spectacles, which leaves Piggy helpless and Ralph’s group without means of making fire. When they go to demand the return of the spectacles, Sam and Eric, twins loyal to Ralph, are tied up, and Piggy is killed by a rock rolled down by Roger, a boy whose attachment to evil scares even Jack. The conch shell, which was the symbol of their democracy, is smashed, and Ralph flees a shower of spears. Jack and his ‘tribe’ – now virtually all the boys – begin to chase Ralph, setting the whole island on fire to smoke him out. He manages to reach the beach ahead of the flames, and falls at the feet of a naval officer. A British ship has arrived, having seen the smoke, and takes all the boys off the island.

In summary, in the space of a few weeks on this idyllic island, three boys are killed, one by accident, one due to an episode of group insanity, and one in cold blood, and a fourth narrowly escapes death at the hands of a bloodthirsty mob.

Style

Golding is a talented writer. Lord of the Flies abounds in memorable lines: there is a compelling narrative style, authentic-sounding dialogue, and poetic description. Here are some examples:

The fair boy stopped and jerked his stockings with an automatic gesture that made the jungle seem for a moment like the Home Counties. [The first appearance of Ralph in Chapter 1]

Roger’s arm was conditioned by a civilisation that knew nothing of him and was in ruins. [Roger was throwing stones at little Henry, but, for the time being, throwing to miss.]

The mask was a thing on its own, behind which Jack hid, liberated from shame and self-consciousness. [Jack’s hunting camouflage]

“Kill the pig. Cut her throat. Spill her blood.” [chant of the hunters]

“Maybe,” he said hesitantly, “maybe there is a beast.” […] “What I mean is, maybe it’s only us.” [Simon]

The world, that understandable and lawful world, was slipping away. [Ralph is shocked that most of the boys believe in the Beast.]

“What are we? Humans? Or animals? Or savages?” [Piggy]

Jack and Ralph faced each other. There was the brilliant world of hunting, tactics, fierce exhilaration, skill; and there was the world of longing and baffled common sense.

“We did everything adults would do. What went wrong?” [Piggy]

“Bollocks to the rules! We’re strong – we hunt! If there’s a beast, we’ll hunt it down! We’ll close in and beat and beat and beat!” [Jack]

“Fancy thinking the Beast was something you could hunt and kill! You knew, didn’t you? I’m part of you? Close, close, close! I’m the reason why it’s no go? Why things are what they are?” [The Beast, to Simon, in his imagination]

At once the crowd surged after it [i.e. Simon, thinking him to be the Beast], poured down the rock, leapt on to the beast, screamed, struck, bit, tore …

[They kill him on the shore and the tide takes him away.]

The water rose further and dressed Simon’s coarse hair with brightness. The line of his cheek silvered and the turn of his shoulder became sculptured marble … Softly, surrounded by a fringe of inquisitive bright creatures, itself a silver shape beneath the steadfast constellations, Simon’s dead body moved out toward the open sea.

“Was it a good—” The air was heavy with unspoken knowledge. Sam twisted and the obscene word shot out of him. “—dance?” Memory of the dance that none of them had attended shook all four boys convulsively. “We left early.” [They are speaking of the wild ‘party’ during which they had all participated in Simon’s murder.]

Ralph wept for the end of innocence, the darkness of man’s heart, and the fall through the air of the true, wise friend called Piggy.

“Jolly good show. Like the Coral Island.” [Naval officer at the end of the book]

Imagery

Golding also has a flair for imagery – he was, after all, a published poet. The boys killing each other on the island mirror the world outside – which was ‘in ruins’. There is animal imagery, and personification. The ocean breathes, the sun’s light is like an arrow, roots scream in the wind. The conch is a fragile symbol of democracy, order and the rule of law. Fire is a friend and enemy, which cooks, comforts, signals and kills. The Beast – the inner evil – is symbolised by the pig’s head and the flies. Like humans, the island has a good (safe and beautiful) side, and a bad side unprotected by the reef.

However, there is a problem with a key image. Piggy’s spectacles are frequently described, in notes for students, as a brilliant metaphor, signifying civilisation and science, as well as vulnerability. They facilitate, allegedly, both vision and fire. But Piggy is short-sighted, and his lenses would be concave, whereas a burning-glass has a convex lens. So Piggy’s spectacles could never light a fire. This is fatal not only to the imagery, but also to the plot, because the final conflict, including Piggy’s death, was precipitated by the theft of them, for the purpose of making fire. It is perhaps not surprising that Golding refused to re-read Lord of the Flies, labelling it “boring and crude.” In an interview with Carey he confessed, “I suppose that basically I despise myself and am anxious not to be discovered, uncovered, detected, rumbled.”

Criticism

Responses to Golding’s work tend to be polarised, varying from the adulatory to the contemptuous. Early reviews of Lord of the Flies included comments like these:

I fell under the terrible spell of this book and so will many others. (Pat Murphy in the Daily Mail)

Vivid and enthralling (John Connell in The Evening News)

Most absorbing and instructive (The Times), praising its ‘vivid realism’

A work of universal significance (Time and Tide)

This beautiful and desperate book, something quite out of the ordinary (Stevie Smith, in The Observer)

By the side of these effusive tributes the comments of Golding’s detractors, written after time had elapsed to enable critical reflection, have a clinical, and possibly more authoritative air:

All thesis novels are rigged. Golding’s thesis requires more rigging than most and it must by definition be escape-proof. The novel functions in a minimal ecology, but even so, and indefinite as it is, it is wrong. The boys never come alive as real boys. They are simply the projected annoyances of a disgruntled English schoolmaster. (Kenneth Rexroth, in The Atlantic, 1965).

Golding presents us with a completely unrealistic model of the origins of human politics. Golding does not show us how a rational society breaks down, but how the conceivably pleasant condition of anarchy disintegrates under the pressure of aggression. Golding has misread the moral of his own fiction. (Kathleen Woodward, 1993)

As Golding’s career developed, those who were prepared to challenge him became more confident. In 1956, following the publication of his third novel, Pincher Martin, C A Lejeune, film critic of The Observer, pronounced, in a radio discussion:

To me it [Pincher Martin] belongs to a class of reading that I deplore, which looks at nothing except what I call the underbelly of the human body, and it sees nothing but the nasty side of it, the horrid side of it.

After his fourth novel, Free Fall, dissenting voices were even more dismissive:

Mr Golding’s moral insights are not particularly original or striking. (Graham Hough in The Listener)

The whole thing is astonishingly and often brutally unpleasant. (The Irish Times).

All these comments could apply equally well to Lord of the Flies.

Golding’s aim in his first three novels was essentially to controvert what he saw as the optimistic and positive view of life held by the uninformed and unintelligent masses. All three novels are ‘antitypes.’ Lord of the Flies is his reversal of the popular survivalist novel, The Coral Island (Ballantyne, 1857), in which Ralph Rover tells of the time when, as a youth, he was cast away on a coral island with two other boys, Jack Martin and Peterkin Gay. (Note the similarity of names to Lord of the Flies.) After several months of successful self-reliance and fun, they had various adventures, defeating pirates and cannibals. Ballantyne wrote, in his reminiscences, “In all my writings I have always tried to advance the cause of Truth and Right and to induce my readers to put their trust in the love of God our Saviour, for this life as well as the life to come.” The Coral Island is mentioned twice in Lord of the Flies, with heavy irony.

In his second published novel, The Inheritors (1955), Golding’s target is the optimistic belief in progress held by writers such as H G Wells. The epigraph to the book is a a quotation from The Outline of History (1920) in which Wells somewhat naively describes Neanderthals as “repulsive” and having “possibly cannibalistic tendencies,” following a stereotype that was popular then, and that prevailed until fairly recently. Golding, in contrast, presents the Neanderthals as a peaceful, imaginative and affectionate race, doomed to be exterminated by a tribe of ruthless invaders – ourselves, Homo sapiens. Progress, in other words, is a facile myth. Things are getting not better, but worse.

Pincher Martin (1956) reverses a 1916 story by H Taprell Dorling (nom de plume ‘Taffrail’) entitled Pincher Martin, O.D.: a story of the inner life of the Royal Navy. In Dorling’s story Martin, a brave and decent Ordinary Seaman, whose ship was sunk by a torpedo, is unexpectedly rescued from drowning, after having resigned himself heroically to death (“Pincher commended his soul to his Maker.”) In Golding’s version a naval officer of the same name but quite the opposite character (“born with his mouth and his flies open”), who initially appears to have survived a torpedo attack, is revealed to have drowned soon after his ship was sunk. The book turns out to be an account of his time in purgatory, or the last few seconds of his life. Again Golding is trying to shock his readers by informing them how horrible life actually is, and rubbishing what he sees as the sentimentality of the older story. The desire to disillusion people, while providing no hope, meaning, framework, context or purpose, is an exceptionally unattractive trait, in people generally, and specifically in an artist.

Carey’s biography concedes that Golding was not always an easy person to live with. Writing in The Guardian on the publication of Carey’s biography, Peter Conrad presents an even more negative picture of his character:

Golding called himself a monster. His imagination lodged a horde of demons, buzzing like flies inside his haunted head, and his dreams rehearsed his guilt in scenarios that read like sketches for incidents in his novels, which they often were …

He understood the Nazis, he said, because he was “of that sort by nature” …

His son-in-law testifies that Golding specialised in belittling others – if that is, he recognised them at all. As Carey notes, he chronically misspelt names because he couldn’t be bothered with people and their pesky claim to exist.

One reason for Golding’s negative view of life is not hard to identify. In 1940 Golding left his teaching job to enlist in the Royal Naval Volunteer Reserve, playing a small part in the sinking of the Bismarck before gaining a commission and command of a rocket-carrying landing craft, which he captained during the D-day assault. No one who has seen such a massive conflict at first hand, who has killed, and has seen comrades killed, can remain untouched by the experience.

Before the Second World War, I believed in the perfectibility of social man; that a correct structure of society produced goodwill; and that you could remove all social ills by a reorganisation of society. After the war, I did not. (interview)

Indeed, Golding’s pessimism was relentless. “Man produces evil as a bee produces honey,” he wrote, in his essay entitled ‘Fable’ (in The Hot Gates, 1965). It is the theme of all his novels, particularly Lord of the Flies. Though superficially impressive, it is no more than a partial truth, and as such, effectively, a falsehood. It is rather like announcing that ‘dogs eat grass’ (which they sometimes do). It is not worthy of consideration as a useful piece of information – it is just an expression of depression, anger, or frustration. Its implication is that people do nothing else but produce evil, and this is manifestly untrue. It is not even supported in Lord of the Flies, for Ralph, Piggy and Simon do nothing but good. In real life, as we all know, people produce good in the way that bees produce honey – that is, spontaneously, and prolifically. Every day brings showers of blessing to every part of the world, from individual instances of courtesy and kindness to massive efforts of global charity or aid, not to mention acts of self-sacrifice and heroism. Yes, people do a lot of bad things as well. We all know that, without having to read Lord of the Flies. What we look for in literature is something to help us make sense of our human situation.

Golding, however, seems to have suffered from two delusions that incapacitated him in this respect. The first is that believing something to be true is sufficient reason for saying it. This doesn’t really need refuting, as, once stated, it is so obviously mistaken. The second is that it is acceptable to communicate negative views about life without offering some sort of solution, consolation, or at least framing. Golding’s formula, in the opinion of many thoughtful readers, is not a recipe for literature, but for self-indulgent ranting.

Conclusion

The Nobel citation for Golding (1983) says that he earned the Prize “for his novels which, with the perspicuity of realistic narrative art and the diversity and universality of myth, illuminate the human condition in the world of today.”

An anonymous reviewer wrote, in 2016, “Why is this constantly appearing on the required reading list of Junior High children? Why is so much required reading for children dark, depressing and tragic? Would it be so awful to have them read something that encourages or gives them hope rather than dread?”

I’m with the anonymous reviewer.

Postscript

Perhaps readers would like to suggest interesting and impactful novels that are not merely ‘dark, depressing and tragic’?

Off the top of my head, I would suggest