by Joseph Shieber

One of the best television comedies of the last decade was The Good Place. Over the course of four seasons, its creator, Michael Schur, and a phenomenal ensemble cast tackled topics that I had thought to be too arcane for network television. The so-called “trolley problem”? Kantian deontology? Utilitarianism? All in the series, served up with Schur’s finely honed comedic chops.

Despite having already had countless opportunities to explore the moral philosophical underpinnings of the show – on Vox alone Schur had a 100-minute interview with Ezra Klein on the moral philosophy of The Good Place and Dylan Matthews wrote an extended piece on “How the Good Place Taught Moral Philosophy to its Characters – And Its Creators” – Schur revisits this territory in his new book, How To Be Perfect: The Correct Answer to Every Moral Question.

To which my first reaction was: Really, Michael Schur? You didn’t have enough to do creating and writing sitcoms for NBC? You just had to sell a philosophy book project to Simon & Schuster? I was almost enraged enough about his amateurish poaching on my professional bailiwick to sit down and craft an unputdownable pitch that would land me an exclusive, even more impressive deal with Universal Television than the one he signed. (Suck it, Schur!)

After I realized that I didn’t know the first thing about pitching a television series, I decided that my fall-back plan would be to read How To Be Perfect and then mock it with haughty disdain – not only at faculty cocktail receptions but also to my immediate friends and family … and here, at 3QD. So I read the book and I can now tell you it’s … really quite good, actually. Read more »

The character of the American abroad is an archetype in American fiction. By placing the American outside of his native country (usually in Europe), writers such as Henry James and James Baldwin were able to explore what constitutes American identity. More often than not, this identity is revealed in their novels not through what the identity contains, but in what it lacks.

The character of the American abroad is an archetype in American fiction. By placing the American outside of his native country (usually in Europe), writers such as Henry James and James Baldwin were able to explore what constitutes American identity. More often than not, this identity is revealed in their novels not through what the identity contains, but in what it lacks. It is a strange enough thing to collect knives. It is a step stranger still to collect sharpening stones; a further abstraction from reality, an auxiliary activity supporting a hobby which is itself a pantomime of preparedness and practicality. No matter. Once one is lodged firmly enough down a rabbit hole, the only options available are to hope for rescue, or to keep crawling deeper. I have clearly chosen the latter.

It is a strange enough thing to collect knives. It is a step stranger still to collect sharpening stones; a further abstraction from reality, an auxiliary activity supporting a hobby which is itself a pantomime of preparedness and practicality. No matter. Once one is lodged firmly enough down a rabbit hole, the only options available are to hope for rescue, or to keep crawling deeper. I have clearly chosen the latter. I am leaving, and I am taking nothing.

I am leaving, and I am taking nothing.

In Barcelona the daily scramble to deliver children to school results in terrible congestion in the upper part of the city, where the more economically privileged send their children. Watching this phenomenon brings back my own school days, when the most embarrassing thing any of us could imagine was being dropped off by parents. If such a thing were necessary for some unavoidable reason, the kids urged their parents to drop them a short distance away from the school so their peers wouldn’t see them getting out of the car. To be seen being coddled in this way was unimaginably embarrassing, almost as bad as having your mother show up to deliver a forgotten lunch box. Everything about parents tended to be embarrassing and much of the time we pretended not to have any. But there was a single exception to the drop-off rule. If the parents happened to own a 1956 Chevrolet, with its futuristic swept-wing design, then it was obligatory to be dropped off at school on some occasion, even if the ride was for only for a couple of blocks, so the other kids could look with sheer envy on this most prestigious possession.

In Barcelona the daily scramble to deliver children to school results in terrible congestion in the upper part of the city, where the more economically privileged send their children. Watching this phenomenon brings back my own school days, when the most embarrassing thing any of us could imagine was being dropped off by parents. If such a thing were necessary for some unavoidable reason, the kids urged their parents to drop them a short distance away from the school so their peers wouldn’t see them getting out of the car. To be seen being coddled in this way was unimaginably embarrassing, almost as bad as having your mother show up to deliver a forgotten lunch box. Everything about parents tended to be embarrassing and much of the time we pretended not to have any. But there was a single exception to the drop-off rule. If the parents happened to own a 1956 Chevrolet, with its futuristic swept-wing design, then it was obligatory to be dropped off at school on some occasion, even if the ride was for only for a couple of blocks, so the other kids could look with sheer envy on this most prestigious possession.  Since my Chair was in International Trade, most of my teaching in Berkeley was in that field of Economics, both at the graduate and undergraduate levels. The undergraduate classes in Berkeley are large, and mine had sometimes more than 200 students, even though this course was meant mostly for later-year undergraduates. Large classes bring you in close touch (particularly in office hours) with a refreshing diversity of young people. But they also bring other kinds of experience.

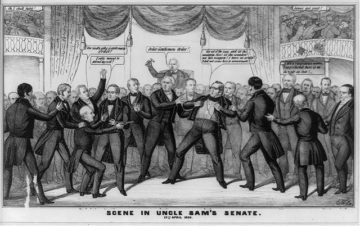

Since my Chair was in International Trade, most of my teaching in Berkeley was in that field of Economics, both at the graduate and undergraduate levels. The undergraduate classes in Berkeley are large, and mine had sometimes more than 200 students, even though this course was meant mostly for later-year undergraduates. Large classes bring you in close touch (particularly in office hours) with a refreshing diversity of young people. But they also bring other kinds of experience. At least Ben was polite about it. The rest of Judge Jackson’s hearing was absolutely awful. If you watched or read or otherwise dared approach the seething caldron of toxicity created by the law firm of Cotton, Cruz, Graham & Hawley (no fee unless a Democrat is smeared) you’ve probably had more than enough, so I’ll try to be brief before getting to more substantive matters.

At least Ben was polite about it. The rest of Judge Jackson’s hearing was absolutely awful. If you watched or read or otherwise dared approach the seething caldron of toxicity created by the law firm of Cotton, Cruz, Graham & Hawley (no fee unless a Democrat is smeared) you’ve probably had more than enough, so I’ll try to be brief before getting to more substantive matters.

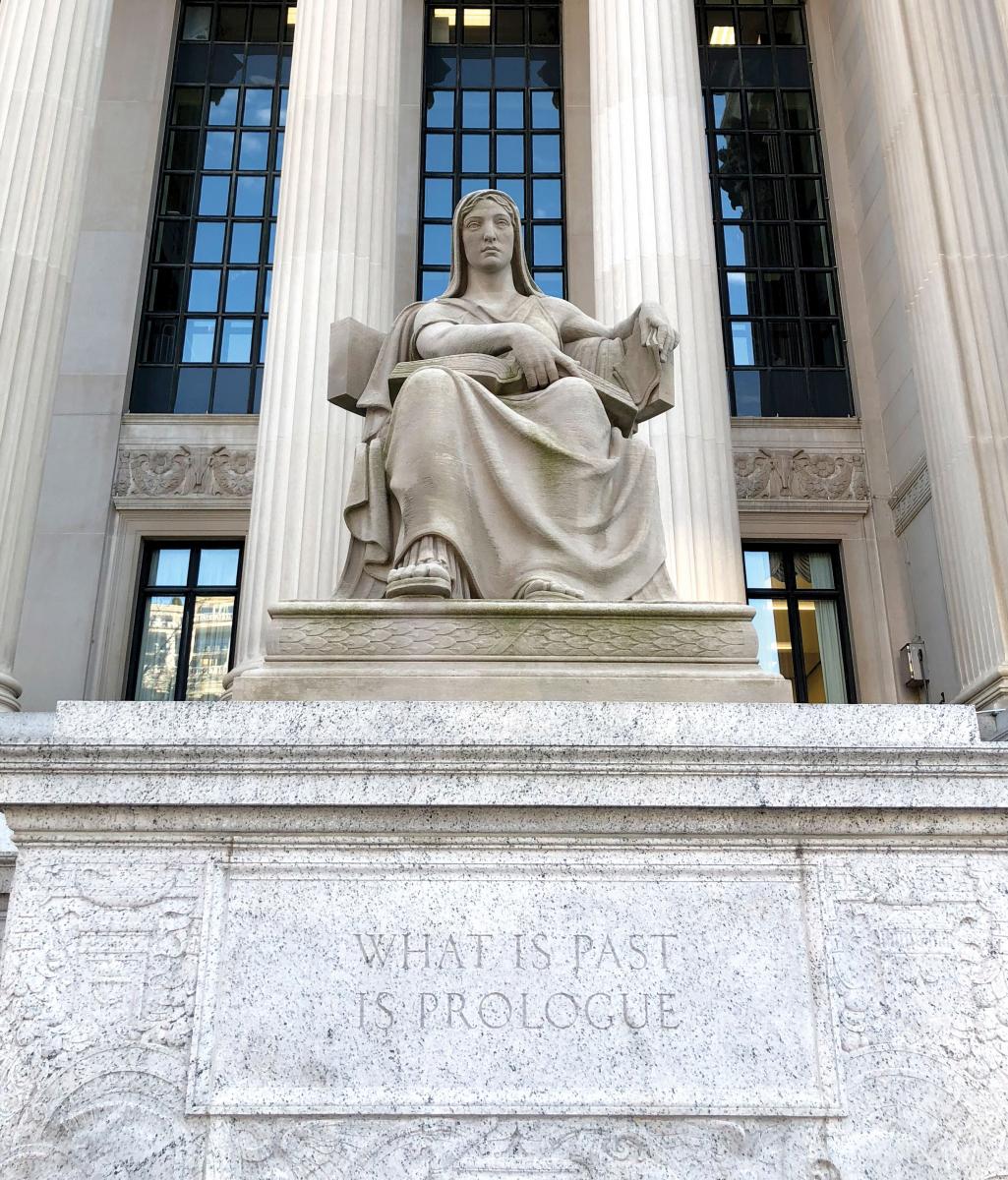

Is the Past Prolog? I’m not convinced. I say this as a professional historian.

Is the Past Prolog? I’m not convinced. I say this as a professional historian. He had a visceral aversion to war, was strongly in favor of social distancing in times of pandemic, and believed it would be a good thing if the Germans turned down their heaters a notch or two.

He had a visceral aversion to war, was strongly in favor of social distancing in times of pandemic, and believed it would be a good thing if the Germans turned down their heaters a notch or two.

Anticipating war in Europe, 2022.

Anticipating war in Europe, 2022. Over the last few weeks, I’ve been spending more time in the office than I have since the start of COVID. I work for a technology start-up, and our New York office used to look and feel just as shows like Silicon Valley portrayed such offices: cool furniture, fancy coffee machines, lots of free snacks, gaming systems and board games piled up in a dedicated room, and lots of young people who gave the office a fun, high energy, even if noisy, vibe. But this visit, while the snacks and coffee machines are still there, the office has a rather ghost town-like feel. There’s been no mandate to return to the office, so for the most part, people haven’t. Every day I saw my colleague Andy who lives in a Manhattan apartment that’s too crowded with family and a dog. He escapes to the office for some peace of quiet. Then there was the receptionist and the facilities manager, who had no choice but to be there. But that was it for regulars. The odd person would float in for a bit, have a meeting, then leave. Is this the future of office life?

Over the last few weeks, I’ve been spending more time in the office than I have since the start of COVID. I work for a technology start-up, and our New York office used to look and feel just as shows like Silicon Valley portrayed such offices: cool furniture, fancy coffee machines, lots of free snacks, gaming systems and board games piled up in a dedicated room, and lots of young people who gave the office a fun, high energy, even if noisy, vibe. But this visit, while the snacks and coffee machines are still there, the office has a rather ghost town-like feel. There’s been no mandate to return to the office, so for the most part, people haven’t. Every day I saw my colleague Andy who lives in a Manhattan apartment that’s too crowded with family and a dog. He escapes to the office for some peace of quiet. Then there was the receptionist and the facilities manager, who had no choice but to be there. But that was it for regulars. The odd person would float in for a bit, have a meeting, then leave. Is this the future of office life?