by Thomas Larson

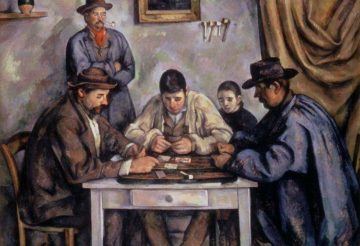

Not long ago, in Philadelphia’s Barnes’ Foundation, I stood close enough to touch Paul Cezanne’s monumental, “The Card Players.” I was mesmerized how paint, texture, composition, and pose achieve an almost granitic-like intensity—three burly men around a table, cards in hands, another man holding a pipe and looking on, and a fifth, a feminine boy, his eyes downcast, echoing and softening the self-absorption of the men before him. The standing man and boy are witnessing the huddle of the three; the two standing invite us to witness the subject and its witnesses, a triangulation of viewer, inner viewers, and inner seen. A painting with its audience internally present and, thus, externally implied.

This canvas, from Cezanne’s final period in the 1890s, is the fifth and most complicated of the paintings he composed of this men-playing-cards motif. Four other “Card Players” were done between 1890 and 1895, all smaller and with fewer figures than this one in the Barnes, measuring 4.5 x 6 feet—but feeling much larger. The figures, who sat for many sketches, are Provence farmhands; the game they appear to be playing is gin rummy, for fun, it seems. No bets are on the table. One critic has called the Barnes painting, a “human still life,” in homage to Cezanne’s love of discovering form and shape with color and palette knife, recognizable as his tilty sensibility when painting fruit on tables and tablecloths in kitchens. He leaves narrative behind in most of these time-stolid works, though the great Barnes’s “The Card Players” with its five massive figures to me does sketch a mysterious tale. Read more »