Spring in Franzensfeste, South Tyrol. Photo taken last week.

Category: Monday Magazine

Though we are an aggregator blog (providing links to content elsewhere) on all other days, on Mondays we have only original writing by our editors and guest columnists. Each of us writes on any subject we wish, and the length of articles generally varies between 1000 and 2500 words. Our writers are free to express their own opinions and we do not censor them in any way. Sometimes we agree with them and sometimes we don’t.Below you will find links to all our past Monday columns, in alphabetical order by last name of the author. Within each columnist’s listing, the entries are mostly in reverse-chronological order (most recent first).

Varieties of Churchgoing in Ladd’s Addition: Part I

by David Oates

Full of good cheer – when does walking not perk me up? – on a too-cool March morning, past houses nicer than mine by several hundred grand with wide verandahs and Craftsman gables, and through a deep urban forest of elms, I make my way towards church.

Church!

Not exactly my normal behavior – not for lo these many decades since achieving my apostasy, my ex-Baptist-ness, and then at length making peace with it. I carried no axe to grind. Though I walked right past a low-slung building with a sign reading – no kidding! – “Chinese Baptist Church.”

I’ll return to that. But today my destination is yet more exotic, you could say, though just one more block away. “St. Sharbel Catholic Church, Maronite Rite” it proclaims itself. Whatever that might mean. My mission was to find out by attending the eleven-o’clock service.

This neighborhood, which I live right next to though not quite in – seems oddly attractive to churches. One of the oldest planned developments in the western US, called “Ladd’s Addition” after its 1891 developer, former mayor William S. Ladd, it forms a square just a half-mile on a side, yet is studded with temples and houses of worship, sanctuaries grand or cozy, surprising or predictable . . . so many varieties of religious belief, so many flavors and even hues. Even in ethnically-challenged Portland.

To what end? Serving what need or what god (or gods)? Who can say. Answer: Me. Or I can try, anyway. Read more »

Charaiveti: Journey From India To The Two Cambridges And Berkeley And Beyond, Part 40

by Pranab Bardhan

All of the articles in this series can be found here.

Andreu Mas-Collel, a mathematical economist from Catalonia, came to Berkeley before I did. He was a student activist in Barcelona, was expelled from his University for activism (those were the days of Franco’s Spain), and later finished his undergraduate degree in a different university, in north-west Spain. When I met him in Berkeley he was already a high-powered theorist using differential topology in general-equilibrium analysis, in ways that were far beyond my limited technical range in economic theory. But when we met, it was our shared interest in history, politics, and culture that immediately made us good friends, and his warm cheerful personality was an added attraction for me. (His wife, Esther, a mathematician from Chile, was as decent a person as she was politically alert).

Andreu Mas-Collel, a mathematical economist from Catalonia, came to Berkeley before I did. He was a student activist in Barcelona, was expelled from his University for activism (those were the days of Franco’s Spain), and later finished his undergraduate degree in a different university, in north-west Spain. When I met him in Berkeley he was already a high-powered theorist using differential topology in general-equilibrium analysis, in ways that were far beyond my limited technical range in economic theory. But when we met, it was our shared interest in history, politics, and culture that immediately made us good friends, and his warm cheerful personality was an added attraction for me. (His wife, Esther, a mathematician from Chile, was as decent a person as she was politically alert).

A few times it so happened that when I went to see some obscure Latin American film in a special showing at a remote movie hall in Berkeley, at the end when the lights came up, I discovered that Andreu was also in the audience, and then we sat down somewhere to discuss the film animatedly. We used to frequently visit each other’s home. One time Romila Thapar, the eminent historian of ancient India, came to visit us from Delhi, and we asked Andreu and Esther to join us. Later he told others about meeting ‘this very impressive woman’ at our place.

When, after a few years, he left Berkeley, first for Harvard, and then in 1990’s back to Barcelona, I sorely missed him. At Harvard Andreu co-authored what is probably the most used graduate textbook in microeconomic theory in the world. In Barcelona he was a Professor at the Pompeu Fabra University. He later joined politics, serving the Catalonian government in different capacities, including as the Minister of Economy and Knowledge in 2010-16. In 2021 he was slapped with a multi-million-euro penalty by the Spanish Court of Auditors for allegedly participating as Minister in activities that led to the abortive Catalonian bid for independence; I believe the case is still pending. Read more »

Monday, April 11, 2022

The Language You Speak Doesn’t Determine How You Think: Demystifying the Sapir-Whorf Hypothesis [sic]

by David J. Lobina

After sort-of dissing James Joyce last time around – 0 comments, though! I expected Colm Tóibín to demur or something – this month I was meant to outline what the language of thought is supposed to be like, thus bringing to an end this series on the relationship between language and thought. But before getting to the details of the representational-conceptual system with which we think our thoughts, and in view of the posts I have devoted to claiming that we don’t think in any natural language – that we really don’t think in any language! – I ought to at least discuss the possibility that different languages may well have an effect on the sort of thoughts available to their speakers.

That there might be cross-linguistic differences in cognition is a rather common belief, in fact – who hasn’t been told that this or that word in this or that language is impossible to translate, for instance? – and it has received quite a bit of attention in both academia and the popular science press. Read more »

Phenology and the Rites of Spring

by Mark Harvey

Out of the blue, between the sea and the sky,

Landward blown on bright, untiring wings;

Out of the South I fly –Maurice Thompson

One of my sisters who is a wildlife biologist often leaves the cinema with an entirely different take on the virtues of any particular movie if it’s set on a natural landscape. Be it an epic love story on the plains of Montana or a character-driven film taking place in the Cascade mountains of the northwest, she and her biologist friends see things through a different lens than you or I. While we might be moved by a love story between a cabin dweller scrapping out an existence while courting a fetching lass from an adjoining homestead, they often leave the same film frustrated and grouchy about how badly and unscientifically the natural world is cast.

“Did you hear that bald eagle?” They’ll say. “That’s not the sound a bald eagle makes! They obviously dubbed the call of a red-tailed hawk over that bald eagle. Who’s going to miss that?”

Well, about 99% of the audience still dabbing their eyes from the happy ending when the homesteaders requite their epic love on the epic landscape.

One thing that seems to really drive my sister and her biologist friends mad is when the director gets the phenology wrong. Phenology, to remind you, is the natural cycle and timing of nature. For example, every spring there is a certain pattern and time frame of flowers blooming, birds returning to the north, insects hatching, and bears coming out of hibernation. So when a film director has the male hero shyly offering flowers to his love interest in one scene and bodice busting in the next, my sister and her crew will cast a clinical eye on the Indian ricegrass and its development between scenes. Read more »

Monday Poem

I . Me .We

so much depends upon the tale we tell ourselves,

words have the force of love or death,

they can raise or raze. In fact, the typhoon of

a single letter, incessantly said,

can ruin nations

the simplest vertical stroke

“I”

or its Russian solo

“Я”

not to mention the tiny bleating duo

“ME”

in the minds of megalomaniacs, or anyone

who stumbles or steps willfully into a cage of mirrors,

can make a hell of families, countries, churches, schools,

because “me” loves the taste of power

while “we” tastes the power of love

Jim, 4/10/22

(“Я” translation: “I”; Pronunciation: Ya)

The ‘Soft’ Impacts of Emerging Technology

by Fabio Tollon

Getting a handle on the various ways that technology influences us is as important as it is difficult. The media is awash with claims of how this or that technology will either save us or doom us. And in some cases, it does seem as though we have a concrete grasp on the various costs and benefits that a technology provides. We know that CO2 emissions from large-scale animal agriculture are very damaging for the environment, notwithstanding the increases in food production we have seen over the years. However, such a ‘balanced’ perspective usually emerges after some time has passed and the technology has become ‘stable’, in the sense that its uses and effects are relatively well understood. We now understand, better than we did in the 1920s, for example, the disastrous effects of fossil fuels and CO2 emissions. We can see that the technology at some point provided a benefit, but that now the costs outweigh those benefits. For emerging technologies, however, such a ‘cost-benefit’ approach might not be possible in practice.

Take a simple example: imagine a private company is accused of polluting a river due to chemical runoff from a new machine they have installed (unfortunately this probably does not require much imagination and can be achieved by looking outside, depending on where you live). In order to determine whether the company is guilty or not we would investigate the effects of their activities. We could take water samples from the river and attempt to show that the chemicals used in the company’s manufacturing process are indeed present in the water. Further, we could make an argument where we show how there is a causal relationship between the presence of these chemicals and certain detrimental effects that might be observed in the area, such as loss of biodiversity, the pollution of drinking water, or an increase in diseases associated with the chemical in question. Read more »

Perceptions

Nikita Kadan. Hold The Thought, Where The Story Was Interrupted, 2014.

Nikita Kadan. Hold The Thought, Where The Story Was Interrupted, 2014.

Wood, metal, plaster, stuffed animals, print on paper, paint.

“Three weeks after the Russian attacks on large parts of the country, the Ukrainian artist Nikita Kadan remains in war-ravaged Kiev. Over the past two decades, Kadan’s work has been exhibited in various group and solo exhibitions in the East and West of Europe. As an artist, Kadan is outspokenly political, producing paintings, sculptures, and installations. Kadan is a member of REP (Revolutionary Experimental Space) and co-founder of Hudrada, a curatorial and activist collective. A few days after the outbreak of the war, the artist sought refuge in Voloshyn Gallery, an exhibition space in a cellar in the center of Kiev, which served as a bomb shelter in the Soviet era. He keeps on working as well as the circumstances allow. Surrounded by artworks, and amid bombs falling overground, Kadan installed an exhibition of works from the gallery’s collection.”

More complications, please

by Charlie Huenemann

“Out of love for mankind, and out of despair at my embarrassing situation, seeing that I had accomplished nothing and was unable to make anything easier than it had already been made, and moved by a genuine interest in those who make everything easy, I conceived it as my task to create difficulties everywhere.” (Johannes Climacus / Søren Kierkegaard, Concluding Unscientific Postscript)

It is entirely possible that we cannot handle the ever rising tide of knowledge. Yes, I am going to presume that it is knowledge — that we are not barking up the wrong axis mundi, that we are not ten days away from the next Einstein who overturns everything, that this time next year we will not look back on today as back when we were mere children. You might ask how I can possibly make this presumption, and you are right to ask. Nevertheless…

We know a helluva lot. It’s really extraordinary if you stop to think about it. Why should the descendants of some savannah primates be able to figure out all this stuff about quarks, penicillin, double-entry bookkeeping, stock derivatives, the rise and fall of psychoanalysis, Bluetooth (well, right, work in progress), and microchip readers? Any ancient alien bookies would have placed the odds heavily against us. But here we are, trying to drink from a veritable firehouse of veritas, swelling our heads most impressively.

As I said, maybe we can’t handle it. What am I saying? Of course we cannot handle it. Look at the guy over there, the one who holds in his palm a device that can tell him that there may be archeological evidence of the Hanging Gardens of Babylon beneath the Euphrates, the one who is watching a video of a dog pooping on a boat. Check your own recently closed tabs. Would you make him or you the lord of the whole of human knowledge? Read more »

Catspeak

by Brooks Riley

Excerpt from a Work-in-progress

by Andrea Scrima

March 1, 2022

I left Florence exactly two years ago, a week after the first Corona lockdowns went into effect on February 22, 2020; I returned to the city for the first time yesterday, just as Russian attacks on Ukraine shifted into full gear. Back in Berlin, the war felt suddenly very close: we share a peculiarly intense, at times numinous northern continental winter light with our neighbors to the East; we are united by weather fronts, massive drifts of leaden, seemingly immobile nimbostratus clouds inching slowly across the North European Plain through Poland and Belarus and drifting farther east and south, eventually yielding to the frigid Siberian High and the weather patterns of the Black Sea Lowland. Moving eastward, the clement maritime climate of the western plains gradually gives way to harsher temperatures: summers are hotter, winters bitter cold. The day before yesterday, as over 100,000 people gathered in Berlin between the Victory Column and the Brandenburg Gate to protest the Russian invasion, the sky was sunny and clear, and although there was still a frigid bite in the air, the snow covering the streets of Lviv and Kharkiv and Kiev had either passed us by or was blown into Ukraine from the northeast. Martius, named after the Roman god of war, marked the beginning of the ancient calendar year and the resumption of military campaigns following a winter hiatus. Today, on the first of this ominous month, a forty-mile-long Russian convoy is approaching Kiev. It’s just above freezing there; precipitation is in the forecast for the next several days, expected to give way to subzero temperatures. People will be bombed out of their homes and forced to flee in the freezing rain; later, the slush on the rubble-strewn roads will turn to ice, making their journey on foot even more arduous. Read more »

Monday Photo

Post-pandemic Predictions

by Carol A Westbrook

I pulled my mask up, making sure to cover my nose and mouth as we walked into the supermarket.

My husband looked at me quizzically.

“Why are you putting on your mask?”

I pulled off my mask and gave him a sheepish grin.

I forgot that the mask mandate had been lifted because the Covid-19 case rate is now so low that the chance of infection was almost negligible. But I know that this is temporary, as we will probably have another spike in the fall with the emergence of yet another Omicron variant. But for now we have a temporary reprieve, and we could get back to “normal.” But what is normal? Two years under the threat of Covid-19 has changed the way we do things. The post-pandemic normal will be different than it was before Covid, and here is how I think things will look.

We have changed the way we shop. For me, and for many other people, this is the first time I’ve actually shopped for groceries in person instead of ordering online. As I walked in, the store felt like a wonderland, so full of good things to buy that I couldn’t make up my mind. Yes, they even had toilet paper! Every brand and any size! (Remember the first few weeks of the lockdown, when one of our biggest fears was to be caught with our pants down, with nothing to wipe our rear ends?) Still, some products were in short supply, with their empty spots glaringly obvious, like a mouth with a missing tooth. Supply chain problems, they said. Read more »

Poem

At My Mother’s Grave in the Putnam Valley —

7000 Miles from Where She Was Born

Mother, I thought I heard an echo

of your rousing words —

“My Life Is Ahead of Me”—

Wrinkles mapped your face

after you flew

from the Kashmir Valley where—

long as I remember—

you raged for a life of dignity —

again losing your mind . . .

Seventy-three is the same age you were

when you spoke those words, yet

mapping my life ahead, I wonder

how stirring now must be

your echo across eternity!

Maryam Kathwari, March 5, 1924 ‑— March 31, 2020

Charaiveti: Journey From India To The Two Cambridges And Berkeley And Beyond, Part 39

by Pranab Bardhan

All of the articles in this series can be found here.

In the Berkeley hills there is a campus bus but the nearest bus stop is about a one-mile walk from my home, if you take a short cut through a meadow, but it gets quite muddy in the rainy season. Still, after some years I opted for taking the campus bus rather than my car on weekdays. One regular passenger I used to meet in the bus was a distinguished nonagenarian, Charles Townes, who had won the 1964 Physics Nobel Prize for inventing the laser (later he was also involved in the team that discovered the black hole at the center of the Milky Way galaxy). In a campus lecture that I once gave on Globalization I was thrilled to see him at the front in the audience. He was active in the campus even in his 100th year, shortly before his death.

In the Berkeley hills there is a campus bus but the nearest bus stop is about a one-mile walk from my home, if you take a short cut through a meadow, but it gets quite muddy in the rainy season. Still, after some years I opted for taking the campus bus rather than my car on weekdays. One regular passenger I used to meet in the bus was a distinguished nonagenarian, Charles Townes, who had won the 1964 Physics Nobel Prize for inventing the laser (later he was also involved in the team that discovered the black hole at the center of the Milky Way galaxy). In a campus lecture that I once gave on Globalization I was thrilled to see him at the front in the audience. He was active in the campus even in his 100th year, shortly before his death.

I also came to know that he was a deeply religious man. He claimed that his invention of the laser came to him like a ‘flash’ akin to religious revelation. When he got the 2005 Templeton Prize that celebrates scientific and spiritual curiosity, he said that “Science and Religion are quite parallel…..Science tries to understand what our universe is like and how it works, including us humans. Religion is aimed at understanding the purpose and meaning of our universe, including our own lives”. This reminded me of what Tagore said to Einstein on the relation between Science and Religion when they met at the latter’s home in Berlin in 1930: “Science… is the impersonal human world of Truths. Religion realizes these Truths and links them up with our deeper needs; our individual consciousness of Truth gains universal significance. Religion applies values to Truth.” Einstein did not fully agree with Tagore, nor do I with either Townes or Tagore. But no one can deny that in interpreting facts scientists cannot be independent of values (this is an important issue in some debates in life sciences now), and I also understand a bit about the possible appeal of deep spirituality even for atheists. Read more »

Monday, April 4, 2022

Politics and Original Sin

by Martin Butler

Beliefs about the essential goodness or badness of human beings have been at the heart of much political theory.[1] A recent book by the political philosopher Lea Ypi succinctly expresses the conflicting approaches. Speaking of her mother she’s says:

Beliefs about the essential goodness or badness of human beings have been at the heart of much political theory.[1] A recent book by the political philosopher Lea Ypi succinctly expresses the conflicting approaches. Speaking of her mother she’s says:

“Everyone, she believed, fought as a matter of course, men and women, young and old, current generations and future ones. Unlike my father, who thought people were naturally good, she thought they were naturally evil. There was no point in trying to make them good; one simply has to channel that evil so as to limit the harm. That’s why she was convinced socialism could never work even under the best circumstances. It was against human nature.”[2]

This negative view of human nature is associated with philosopher Thomas Hobbes, and the more positive view with Jean-Jacques Rousseau. Whether this is entirely justified is an open question, and I do not want to challenge the idea of human nature as such. Human beings like sweet things, they are sexual beings, they are on the whole social, seeking the approval of their fellows, and so on. The idea of human nature seems perfectly reasonable. I do, however, want to examine how the idea that human beings are naturally bad should affect our political beliefs, if indeed it should affect them at all. Read more »

Did Kurt Gödel Predict the January 6th Capitol Attack?

by Steve Gimbel and Gwydion Suilebhan

Kurt Gödel, one of the most important logicians of the 20th century, is best known for his incompleteness theorem, which proves that any attempt to formulate a logical basis for arithmetic will either be unsound or incomplete. He was also famous for being a strange egg: walking around in a heavy coat in the summer, attending an occasional séance, and living in fear that someone was trying to poison him. There are lots of odd anecdotes about Gödel, but one happens to be a particular favorite among historians of logic: the story of his becoming an American citizen.

Gödel taught at the University of Vienna. After Hitler’s invasion of Austria, the Anschluss, Gödel would frequently be accosted by Nazi hoodlums in the street who assumed that because he was a skinny nerd with glasses, he must be Jewish. He wasn’t. Eventually, he had enough. He relocated to America, settling in Princeton, where he took up residence at the Institute for Advanced Study.

He became friendly with the Institute’s most famous scholar, Albert Einstein. Gödel had done some mathematical work exposing some of the stranger possibilities of the general theory of relativity, including the possibility of time travel, where a fast-moving electron could collide with itself if there was a bizarre enough distribution of matter and energy throughout space and time. Einstein and Gödel had plenty to discuss as they took walks together in their adopted homeland.

Before long, Einstein and economist Oskar Morgenstern convinced Gödel that he should become an American citizen. Looking into the process, Gödel learned that he would have to swear an oath to obey and defend the Constitution of the United States. Read more »

Perceptions

Sughra Raza. Self Portrait at Gas Station, April 3, 2022.

Sughra Raza. Self Portrait at Gas Station, April 3, 2022.

Why aren’t people paid according to their social contribution?

by Emrys Westacott

What should we do with our leisure? In his Politics, Aristotle identifies this as a fundamental philosophical question. Leisure, here, means freedom from necessary labor. If we have to spend much of our time working, or recuperating in order to work more, the question hardly arises. But if we are free from the yoke of necessity, how we answer the question will say much about our conception of the good life for a human being.

It is to be hoped that the question will one day become the primary question confronting humanity. This hope rests on the prospect of a world in which technological progress has advanced to such a degree that no one needs to work more than a few hours per week in order to enjoy a reasonably comfortable and secure existence. Before the industrial revolution such an idea was a mere fantasy; but given the rate of technological progress over the past two hundred years–and particularly in light of the recent digital revolution and the advent of what has been called “the second machine age”–the prospect of a much more leisurely life for those who want it is at least conceivable.

The fifteen-hour work week envisaged by John Maynard Keynes in “Economic Possibilities for our Grandchildren” (1930) is hardly just around the corner, though. One problem, of course, is that there are some kinds of work that are not easily automated. Consider home care for the disabled, sick, and elderly. Machines are capable of cognitive tasks far beyond the ability of humans, yet many of the basic manual tasks caregivers perform are still very difficult for robots to replicate. Beyond that, though, caregivers also provide human contact and companionship. For machines to offer an adequate substitute for this takes us well into the realm of science fiction (which is not say into the realm of impossibility).

The deeper problem, though, is political rather than technological. Read more »

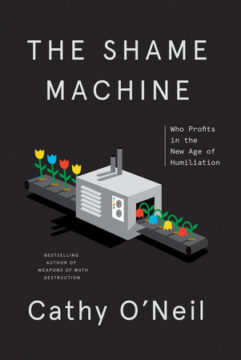

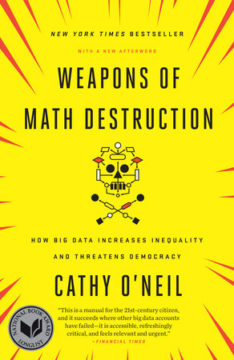

The Shame Machine: Author Cathy O’Neil Interviewed by Danielle Spencer

by Danielle Spencer

Cathy O’Neil’s The Shame Machine: Who Profits in the New Age of Humiliation (Crown) was released on March 22, 2022. O’Neil is the author of the bestselling Weapons of Math Destruction: How Big Data Increases Inequality and Threatens Democracy (Crown 2016) which won the Euler Book Prize and was longlisted for the National Book Award. She received her PhD in mathematics from Harvard and has worked in finance, tech, and academia. She launched the Lede Program for data journalism at Columbia University and recently founded ORCAA, an algorithmic auditing company. O’Neil is a regular contributor to Bloomberg Opinion.

Danielle Spencer: Can you speak a bit about your background and what led you to write this book?

Cathy O’Neil: I’m a mathematician and a child of two mathematicians. Very nerd-centered childhood, where science was the religion of the household. They were otherwise atheists. I became a data scientist at some point, also a hedge fund analyst.

And then I started trying to warn people about the dangers of algorithms when we trust them blindly. I wrote a book called Weapons of Math Destruction, and in doing so I interviewed a series of teachers and principals who were being tested by this new-fangled algorithm called the value-added model for teachers. And it was high stakes. They were being denied tenure or even fired based on low scores, but nobody could explain their scores. Or shall I say, when I asked them, “Did you ask for an explanation of the score you got?” They often said, “Well, I asked, but they told me it was math and I wouldn’t understand it.”

And then I started trying to warn people about the dangers of algorithms when we trust them blindly. I wrote a book called Weapons of Math Destruction, and in doing so I interviewed a series of teachers and principals who were being tested by this new-fangled algorithm called the value-added model for teachers. And it was high stakes. They were being denied tenure or even fired based on low scores, but nobody could explain their scores. Or shall I say, when I asked them, “Did you ask for an explanation of the score you got?” They often said, “Well, I asked, but they told me it was math and I wouldn’t understand it.”

That was the first moment I thought, “Oh my God, shame is so powerful.” That was math shame, evidently, because it wouldn’t have worked on me. [laughs] I’m a mathematician. You’re not going to shame me on math. If you tell me I wouldn’t understand something because it’s math, I’d say, “Dude, buster, if you can’t explain it to me, that’s your problem—not mine.” I would just be bulletproof to math-shaming. Read more »