by Ada Bronowski

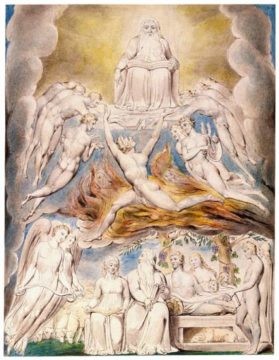

The weird and wonderful painter Johann Heinrich Füssli (1741-1825), whose most famous work is undoubtedly The Nightmare from 1781, presents an interesting case of dysmorphia. The Nightmare is as disturbing as it is entrancing with its undercurrents of erotic terror and dreamy fantasy, but its surface horror is perhaps not what is most shocking about it. What if the artist’s self-portrait was lurking somewhere across the horse and the goblin?

Neither a historical scene, nor an illustration of a literary reference, the subject-matter of The Nightmare is entirely made up, which, in its 18th century context, makes it rather unique and draws alarming attention to the mind from which it came. Over the same period, Füssli drew a number of self-portraits which, when confronted with portraits of the artists made by others, betray a notable distance between the way the artist appeared to others and the way he saw himself. In a neat and well-rounded Paris exhibition, Füssli: Entre Reve et Fantastique, currently on show at the Musée Jacquemart-André, a few concentrated rooms spin a twisted tale around the windmills of the artist’s mind.

Füssli made his career in England, but he was born in German-speaking Switzerland and spent the formative years of his youth travelling through Europe, settling for a period of eight or so years in Rome. Ordained as a pastor at age twenty, his penchant for provocation and a passion for art kept him away from the pulpits all his life, to end up as Keeper and professor of drawing at the Royal Academy in London. Read more »

In 1965, John McPhee wrote an article for The New Yorker titled “

In 1965, John McPhee wrote an article for The New Yorker titled “

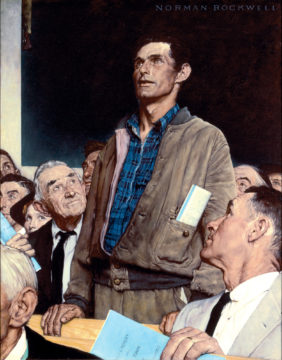

Watching the Oathkeepers cry during the federal court trials under the charge of sedition, I considered the fate of seditious Loyalists during the Revolutionary War whom they most closely resemble in the topsy-turvy world of contemporary politics. The Revolutionary War was a civil war, combatants were united with a common language and heritage that made each side virtually indistinguishable. Even before hostilities were underway, spies were everywhere, and treason inevitable. Defining treason is the first step in delineating one country from another, and indeed, the five-member “Committee on Spies’ ‘ was organized before the Declaration of Independence was written.

Watching the Oathkeepers cry during the federal court trials under the charge of sedition, I considered the fate of seditious Loyalists during the Revolutionary War whom they most closely resemble in the topsy-turvy world of contemporary politics. The Revolutionary War was a civil war, combatants were united with a common language and heritage that made each side virtually indistinguishable. Even before hostilities were underway, spies were everywhere, and treason inevitable. Defining treason is the first step in delineating one country from another, and indeed, the five-member “Committee on Spies’ ‘ was organized before the Declaration of Independence was written.

In 2022, I worked harder than before to keep my students’ tables free of smartphones. That this is a matter for negotiation at all, is because on the surface, the devices do so many things, and students often make a reasonable, possibly-good-faith case for using it for a specific purpose. I forgot my calculator; can I use my phone? No, thank you for asking, but you won’t be needing a calculator; just start with this exercise here, and don’t forget to simplify your fractions. Can I listen to music while I work? Yeah, uhm, no, I happen to be a big believer in collaborative work, I guess. Can I check my solutions online please? Ah, very good; but instead, use this printout that I bring to every one of your classes these days. I’m done, can I quickly look up my French homework? That’s a tough one, but no; it’s seven minutes to the bell anyway and I prepared a small Kahoot quiz on today’s topic. (So everyone please get your phones out.)

In 2022, I worked harder than before to keep my students’ tables free of smartphones. That this is a matter for negotiation at all, is because on the surface, the devices do so many things, and students often make a reasonable, possibly-good-faith case for using it for a specific purpose. I forgot my calculator; can I use my phone? No, thank you for asking, but you won’t be needing a calculator; just start with this exercise here, and don’t forget to simplify your fractions. Can I listen to music while I work? Yeah, uhm, no, I happen to be a big believer in collaborative work, I guess. Can I check my solutions online please? Ah, very good; but instead, use this printout that I bring to every one of your classes these days. I’m done, can I quickly look up my French homework? That’s a tough one, but no; it’s seven minutes to the bell anyway and I prepared a small Kahoot quiz on today’s topic. (So everyone please get your phones out.) Lita Albuquerque. Southern Cross, 2014, from Stellar Axis: Antarctica, Ross Ice Shelf, Antarctica, 2006.

Lita Albuquerque. Southern Cross, 2014, from Stellar Axis: Antarctica, Ross Ice Shelf, Antarctica, 2006.

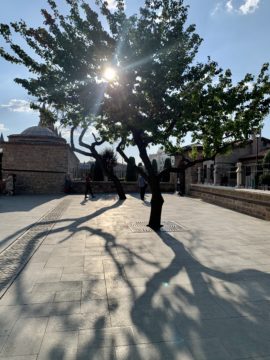

A tree in the vicinity of Rumi’s tomb has me transfixed. It isn’t the tree, actually, it is the force of attraction between tree-branch and sun-ray that seems to lift the tree off the ground and swirl it in sunshine, casting filigreed shadows on the concrete tiles across the courtyard. The tree’s heavenward reach is so magnificent that not only does it seem to clasp the sun but it spreads a tranquil yet powerful energy far beyond itself. It is easy to forget that the tree is small. I consider this my first meeting with Shams.

A tree in the vicinity of Rumi’s tomb has me transfixed. It isn’t the tree, actually, it is the force of attraction between tree-branch and sun-ray that seems to lift the tree off the ground and swirl it in sunshine, casting filigreed shadows on the concrete tiles across the courtyard. The tree’s heavenward reach is so magnificent that not only does it seem to clasp the sun but it spreads a tranquil yet powerful energy far beyond itself. It is easy to forget that the tree is small. I consider this my first meeting with Shams.

I’m going to date myself in a significant way now: when I was in high school, we had to use books of trigonometric tables to look up sine and cosine values. I’m not so old that it wasn’t possible to get a calculator that could tell you the answer, but I’m assuming that the rationale at my school was that this was cheating in some way and that we needed to understand how actually to look things up. I know that sounds quaint now. I also remember when I used an actual book as a dictionary to look up how to spell words. Yes, youth of today, there were actual books that were dictionaries, and you had to find your word in there, which could be challenging if you didn’t know how to spell the word to begin with.

I’m going to date myself in a significant way now: when I was in high school, we had to use books of trigonometric tables to look up sine and cosine values. I’m not so old that it wasn’t possible to get a calculator that could tell you the answer, but I’m assuming that the rationale at my school was that this was cheating in some way and that we needed to understand how actually to look things up. I know that sounds quaint now. I also remember when I used an actual book as a dictionary to look up how to spell words. Yes, youth of today, there were actual books that were dictionaries, and you had to find your word in there, which could be challenging if you didn’t know how to spell the word to begin with.

Now that the hangover from New Year’s Eve is abating for many, and we might be freshly open to some self-improvement, consider a Buddhist view of using meditation to tackle addictions. I don’t just mean for substance abuse, but also for that incessant drive to check social media just once more before starting our day or before we finally lull ourselves to sleep by the light of our devices, or the drive to buy the store out of chocolates at boxing day sales. Not that there’s anything wrong with that on its own– it’s a sale after all–but when actions are compulsive instead of intentional, then this can be a different way of approaching the problem from the typical route. I’m not a mental health professional, but this is something I’ve finally tried with earnest and found helpful, but it took a very different understanding of it all to get just this far (which is still pretty far from where I’d like to be).

Now that the hangover from New Year’s Eve is abating for many, and we might be freshly open to some self-improvement, consider a Buddhist view of using meditation to tackle addictions. I don’t just mean for substance abuse, but also for that incessant drive to check social media just once more before starting our day or before we finally lull ourselves to sleep by the light of our devices, or the drive to buy the store out of chocolates at boxing day sales. Not that there’s anything wrong with that on its own– it’s a sale after all–but when actions are compulsive instead of intentional, then this can be a different way of approaching the problem from the typical route. I’m not a mental health professional, but this is something I’ve finally tried with earnest and found helpful, but it took a very different understanding of it all to get just this far (which is still pretty far from where I’d like to be).