Michael Fried at Artforum:

IF A SINGLE QUESTION is guiding for our understanding of Manet’s art during the first half of the 1860s, it is this: What are we to make of the numerous references in his paintings of those years to the work of the great painters of the past? A few of Manet’s historically aware contemporaries recognized explicit references to past art in some of his important pictures of that period; and by the time he died his admirers tended to play down the paintings of the first half of the sixties, if not of the entire decade, largely because of what had come to seem their overall dependence on the Old Masters. By 1912 Blanche could claim, in a kind of hyperbole, that it was impossible to find two paintings in Manet’s oeuvre that had not been inspired by other paintings, old or modern. But it has been chiefly since the retrospective exhibition of 1932 that historians investigating the sources of Manet’s art have come to realize concretely the extent to which it is based upon specific paintings, engravings after paintings, and original prints by artists who preceded him. It is now clear, for example, that most of the important pictures of the sixties depend either wholly or in part on works by Velasquez, Goya, Rubens, Van Dyck, Raphael, Titian, Giorgione, Veronese, Le Nain, Watteau, Chardin, Courbet . . . This by itself is an extraordinary fact, one that must be accounted for if Manet’s enterprise is to be made intelligible.

IF A SINGLE QUESTION is guiding for our understanding of Manet’s art during the first half of the 1860s, it is this: What are we to make of the numerous references in his paintings of those years to the work of the great painters of the past? A few of Manet’s historically aware contemporaries recognized explicit references to past art in some of his important pictures of that period; and by the time he died his admirers tended to play down the paintings of the first half of the sixties, if not of the entire decade, largely because of what had come to seem their overall dependence on the Old Masters. By 1912 Blanche could claim, in a kind of hyperbole, that it was impossible to find two paintings in Manet’s oeuvre that had not been inspired by other paintings, old or modern. But it has been chiefly since the retrospective exhibition of 1932 that historians investigating the sources of Manet’s art have come to realize concretely the extent to which it is based upon specific paintings, engravings after paintings, and original prints by artists who preceded him. It is now clear, for example, that most of the important pictures of the sixties depend either wholly or in part on works by Velasquez, Goya, Rubens, Van Dyck, Raphael, Titian, Giorgione, Veronese, Le Nain, Watteau, Chardin, Courbet . . . This by itself is an extraordinary fact, one that must be accounted for if Manet’s enterprise is to be made intelligible.

more here.

Sughra Raza. Early Winter Shapes, January 2022.

Sughra Raza. Early Winter Shapes, January 2022. If we are to believe the most prominent of the writers we now lump under the category of “existentialism,” human suffering in the modern world is rooted in nihilism. But I wonder whether this is the best lens through which to view human suffering.

If we are to believe the most prominent of the writers we now lump under the category of “existentialism,” human suffering in the modern world is rooted in nihilism. But I wonder whether this is the best lens through which to view human suffering.

Blanchett’s performance has been much praised, and it is indeed a tremendous thing: she must be near the head of the queue for an Oscar this year. It’s a great performance in a genuinely worthwhile and absorbing film. I don’t think it really expands our understanding of the themes it features: power and the exploitation young hopefuls by the (seemingly) all powerful star, the question of great art and flawed artists and so on, but it’s possible to come out of the movie thinking that it has. Blanchett’s performance has a lot to do with that. So a great performance in a very good rather than great film (assuming such categories can really be employed so neatly).

Blanchett’s performance has been much praised, and it is indeed a tremendous thing: she must be near the head of the queue for an Oscar this year. It’s a great performance in a genuinely worthwhile and absorbing film. I don’t think it really expands our understanding of the themes it features: power and the exploitation young hopefuls by the (seemingly) all powerful star, the question of great art and flawed artists and so on, but it’s possible to come out of the movie thinking that it has. Blanchett’s performance has a lot to do with that. So a great performance in a very good rather than great film (assuming such categories can really be employed so neatly).

In

In  For the last several years, elected Republicans, full of anti-trans zeal, have challenged their opponents to define the word “woman.” They aren’t really curious. They’re setting a rhetorical trap. They’re taking a word that seems to have a simple meaning, because the majority of people who identify as women resemble each other in some ways, then refusing to consider any of the people who don’t.

For the last several years, elected Republicans, full of anti-trans zeal, have challenged their opponents to define the word “woman.” They aren’t really curious. They’re setting a rhetorical trap. They’re taking a word that seems to have a simple meaning, because the majority of people who identify as women resemble each other in some ways, then refusing to consider any of the people who don’t. Indeed, the

Indeed, the  The blue, fin, bowhead, gray, humpback, right and sperm whales are the largest animals alive today. In fact, the blue whale is the largest-known creature ever on Earth, topping even the biggest of the dinosaurs.

The blue, fin, bowhead, gray, humpback, right and sperm whales are the largest animals alive today. In fact, the blue whale is the largest-known creature ever on Earth, topping even the biggest of the dinosaurs. In late 1968, the train and bus stations of Chinese cities filled with sobbing adolescents and frightened parents. The authorities had decreed that teenagers – deployed by

In late 1968, the train and bus stations of Chinese cities filled with sobbing adolescents and frightened parents. The authorities had decreed that teenagers – deployed by  If the coconut symbolizes the natural bounty of the tropical zone in many people’s minds, it is often used to “explain” the human poverty frequently found in the zone. A common assumption in rich countries is that poor countries are poor because their people do not work hard. And given that most, if not all, poor countries are in the tropics, they often attribute the lack of work ethic of the people in poor countries to the easy living that they supposedly get thanks to the bounty of the tropics. In the tropics, it is said, food grows everywhere (bananas, coconuts, mangoes—the usual imagery goes), while the high temperature means that people don’t need sturdy shelter or much clothing.

If the coconut symbolizes the natural bounty of the tropical zone in many people’s minds, it is often used to “explain” the human poverty frequently found in the zone. A common assumption in rich countries is that poor countries are poor because their people do not work hard. And given that most, if not all, poor countries are in the tropics, they often attribute the lack of work ethic of the people in poor countries to the easy living that they supposedly get thanks to the bounty of the tropics. In the tropics, it is said, food grows everywhere (bananas, coconuts, mangoes—the usual imagery goes), while the high temperature means that people don’t need sturdy shelter or much clothing.

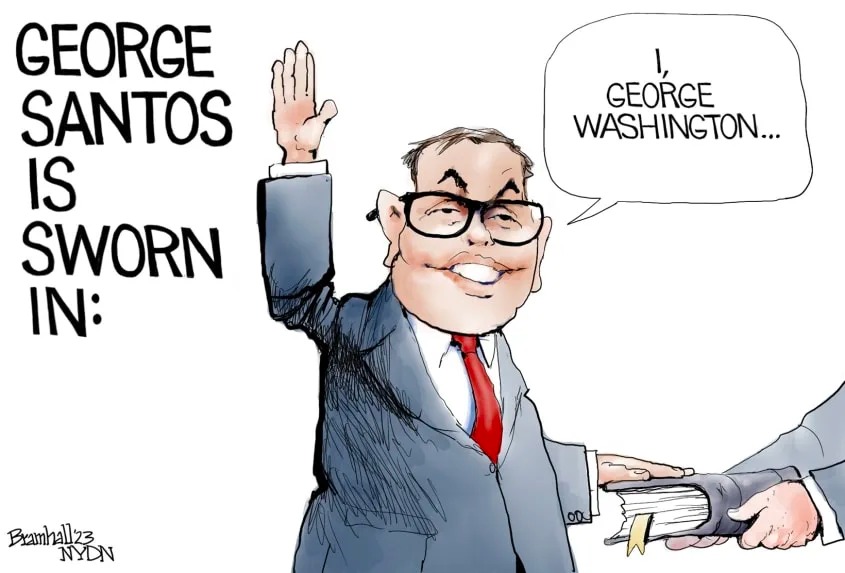

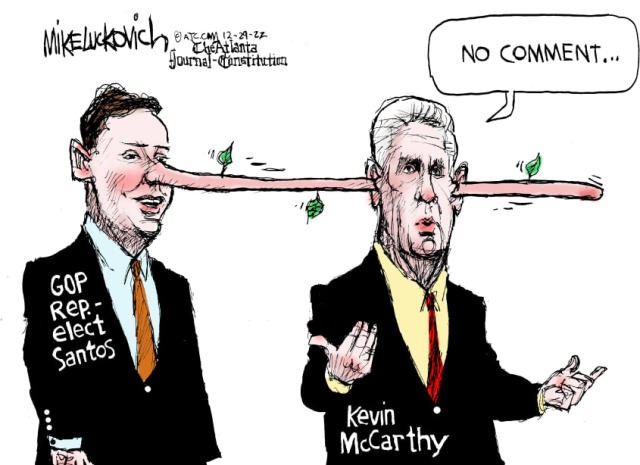

WASHINGTON — It’s not a pretty sight when pols lose power. They wilt, they crumple, they cling to the vestiges, they mourn their vanished entourage and perks. How can their day in the sun be over? One minute they’re running the world and the next, they’re in the room where it doesn’t happen.

WASHINGTON — It’s not a pretty sight when pols lose power. They wilt, they crumple, they cling to the vestiges, they mourn their vanished entourage and perks. How can their day in the sun be over? One minute they’re running the world and the next, they’re in the room where it doesn’t happen.