Month: January 2023

Thursday Poem

What I’m Doing Here

I do not know if the world has lied

I have lied

I do not know if the world has conspired against love

I have conspired against love

The atmosphere of torture is no comfort

I have tortured

Even without the mushroom cloud

still I would have hated

Listen

I would have done the same things

even if there were no death

I will not be held like a drunkard

under the cold tap of facts

I refuse the universal alibi

Like an empty telephone booth passed at night

and remembered

like mirrors in a movie palace lobby consulted

only on the way out

I wait

for each one of you to confess

by Leonard Cohen

from Selected Poems, 1956-1968

Viking Press, 1968

Herbert Read: The Art of Everyday Life

Nicholas Burman in Jacobin:

In a natural society there will be no precious or privileged beings called artists,” Herbert Read declares in his 1941 essay To Hell With Culture. “There will only be workers.” The eightieth anniversary of this essay’s publication provides an excuse to return to Read and consider him and the relevancy of his work today.

Read is often described as a contradictory figure: a bow-tied, softly spoken pacifist; an art critic open to automated processes but nostalgic for the medieval crafts guilds; a philosopher who stressed the importance of workers owning the means of production but who was far from an orthodox Marxist.

While being an early adopter of Nietzsche made him a Europeanizer of British criticism, he also stuck closely to the traditional objects of art history while continental counterparts expanded their analyses to include cities and social movements. Generally friendly toward him, George Orwell wrote that Read’s “open-mindedness has been his strength and weakness.”

More here.

All biology is computational biology

Florian Markowetz in PLOS Biology:

Here, I argue that computational thinking and techniques are so central to the quest of understanding life that today all biology is computational biology. Computational biology brings order into our understanding of life, it makes biological concepts rigorous and testable, and it provides a reference map that holds together individual insights. The next modern synthesis in biology will be driven by mathematical, statistical, and computational methods being absorbed into mainstream biological training, turning biology into a quantitative science.

Here, I argue that computational thinking and techniques are so central to the quest of understanding life that today all biology is computational biology. Computational biology brings order into our understanding of life, it makes biological concepts rigorous and testable, and it provides a reference map that holds together individual insights. The next modern synthesis in biology will be driven by mathematical, statistical, and computational methods being absorbed into mainstream biological training, turning biology into a quantitative science.

More here.

‘We do our work because we are angry’: Navalny’s right-hand woman Maria Pevchikh on taking on Putin

Carole Cadwalladr in The Guardian:

Two years ago this week, the leader of the Russian opposition, Alexei Navalny, flew into Moscow knowing that he faced certain arrest and imprisonment. It was an extraordinary act of courage and leadership. He had only just recovered from an attempt on his life after collapsing on a plane poisoned with what was later found to be the nerve agent novichok. He was not meant to survive.

Two years ago this week, the leader of the Russian opposition, Alexei Navalny, flew into Moscow knowing that he faced certain arrest and imprisonment. It was an extraordinary act of courage and leadership. He had only just recovered from an attempt on his life after collapsing on a plane poisoned with what was later found to be the nerve agent novichok. He was not meant to survive.

“There was no way he wouldn’t have gone back to Moscow,” the investigative journalist Maria Pevchikh tells me. “That wasn’t even on the table.” As the head of investigations for the Anti-Corruption Foundation (FBK), the organisation founded by Navalny, Pevchikh worked alongside him for a decade and was with him in Siberia when he was poisoned.

“We prepared for it very well,” she says of Navalny’s absence. And then hesitates. “It’s just a very noticeable loss. We’re fully functioning, probably better than before. But we lost a lot of our spirit. We do our work because we’re angry.”

More here.

How well does ChatGPT do Physics?

Rereading Russian Classics in the Shadow of the Ukraine War

Elif Batuman in The New Yorker:

The first and only time I visited Ukraine was in 2019. My book “The Possessed”—a memoir I had published in 2010, about studying Russian literature—had recently been translated into Russian, along with “The Idiot,” an autobiographical novel, and I was headed to Russia as a cultural emissary, through an initiative of pen America and the U.S. Department of State. On the way, I stopped in Kyiv and Lviv: cities I had only ever read about, first in Russian novels, and later in the international news. In 2014, security forces had killed a hundred protesters at Kyiv’s Independence Square, and Russian-backed separatists had declared two mini-republics in the Donbas. Nearly everyone I met on my trip—journalists, students, cultural liaisons—seemed to know of someone who had been injured or killed in the protests, or who had joined the volunteer army fighting the separatists in the east.

The first and only time I visited Ukraine was in 2019. My book “The Possessed”—a memoir I had published in 2010, about studying Russian literature—had recently been translated into Russian, along with “The Idiot,” an autobiographical novel, and I was headed to Russia as a cultural emissary, through an initiative of pen America and the U.S. Department of State. On the way, I stopped in Kyiv and Lviv: cities I had only ever read about, first in Russian novels, and later in the international news. In 2014, security forces had killed a hundred protesters at Kyiv’s Independence Square, and Russian-backed separatists had declared two mini-republics in the Donbas. Nearly everyone I met on my trip—journalists, students, cultural liaisons—seemed to know of someone who had been injured or killed in the protests, or who had joined the volunteer army fighting the separatists in the east.

As the visiting author of two books called “The Possessed” and “The Idiot,” I got to hear a certain amount about people’s opinions of Dostoyevsky. It was explained to me that nobody in Ukraine wanted to think about Dostoyevsky at the moment, because his novels contained the same expansionist rhetoric as was used in propaganda justifying Russian military aggression. My immediate reaction to this idea was to bracket it off as an understandable by-product of war—as not “objective.”

More here.

An ant’s sense of smell is so strong, it can sniff out cancer

Dino Grandini in The Washington Post:

The ant oncologist will see you now.

The ant oncologist will see you now.

Ants live in a world of odor. Some species are completely blind. Others rely so heavily on scent that ones that lose track of a pheromone trail march in a circle, until dying of exhaustion. Ants have such a refined sense of smell, in fact, that researchers are now training them to detect the scent of human cancer cells.

A study published this week in the journal Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences highlights a keen ant sense and underscores how someday we may use sharp-nosed animals — or, in the case of ants, sharp-antennaed — to detect tumors quickly and cheaply. That’s important because the sooner that cancer is found, the better the chances of recovery. “The results are very promising,” said Baptiste Piqueret, a postdoctoral fellow at the Max Planck Institute for Chemical Ecology in Germany who studies animal behavior and co-wrote the paper. He added, however: “It’s important to know that we are far from using them as a daily way to detect cancer.”

More here. (Note: Thanks Ali)

Julia Mossbridge – Why Is Consciousness So Baffling?

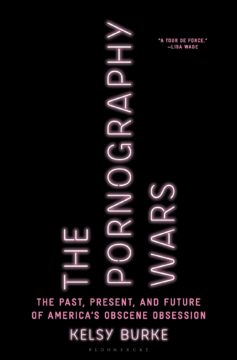

History Of Smut

Whitney Strub at the LARB:

Turning toward the contemporary allows Burke to undertake firsthand observation, learning in the process that antiporn and sex-positive conferences share an affinity for dreary airport hotels. She masterfully profiles individuals involved in the porn wars, writing with empathy and nuance as she speaks with performers, conservative women, and a young “recovery coach” entrepreneur who parlayed his experience with porn addiction (a hotly contested concept, as Burke notes, with competing parties flinging lawsuits at one another constantly) into a career. None of these people collapses into caricature, and Burke allows ambivalence to hang productively in the air. A woman who produced material for Kink.com has come to accept that some of her audience was “rapists or aspiring rapists,” but she doesn’t renounce her work. One young woman who became a performer after majoring in women’s studies endured sexual harassment and career sabotage from her agent before a horrifying European shoot, in which she was pressured into a double anal scene despite never having had anal sex, leaving her in an urgent care facility with an infected rectum. As Burke unblinkingly narrates this, we prepare for the inevitable twist of her rebirth as an antiporn speaker; instead, she remains in the industry, jaded, critical, and now independent on OnlyFans, but still protective of sex work as a labor sector.

Turning toward the contemporary allows Burke to undertake firsthand observation, learning in the process that antiporn and sex-positive conferences share an affinity for dreary airport hotels. She masterfully profiles individuals involved in the porn wars, writing with empathy and nuance as she speaks with performers, conservative women, and a young “recovery coach” entrepreneur who parlayed his experience with porn addiction (a hotly contested concept, as Burke notes, with competing parties flinging lawsuits at one another constantly) into a career. None of these people collapses into caricature, and Burke allows ambivalence to hang productively in the air. A woman who produced material for Kink.com has come to accept that some of her audience was “rapists or aspiring rapists,” but she doesn’t renounce her work. One young woman who became a performer after majoring in women’s studies endured sexual harassment and career sabotage from her agent before a horrifying European shoot, in which she was pressured into a double anal scene despite never having had anal sex, leaving her in an urgent care facility with an infected rectum. As Burke unblinkingly narrates this, we prepare for the inevitable twist of her rebirth as an antiporn speaker; instead, she remains in the industry, jaded, critical, and now independent on OnlyFans, but still protective of sex work as a labor sector.

more here.

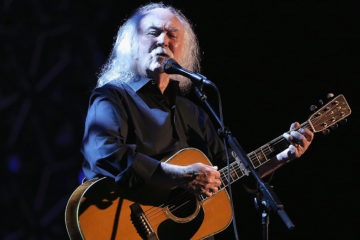

David Crosby Understood the Sharpness of Despair

Amanda Petrusich at The New Yorker:

However cantankerous or stubborn Crosby was offstage, when performing, he was seized by a kind of silent joy. You could see it spreading across his face, loosening his features. Music softened him. In his later years, he wore a white mustache, long frizzy hair, and an omnipresent red beanie (knitted by his wife, Jan). He looked like someone who might sell you some garden compost. He looked salty. Performing was the one thing that seemed to reliably animate and excite him.

However cantankerous or stubborn Crosby was offstage, when performing, he was seized by a kind of silent joy. You could see it spreading across his face, loosening his features. Music softened him. In his later years, he wore a white mustache, long frizzy hair, and an omnipresent red beanie (knitted by his wife, Jan). He looked like someone who might sell you some garden compost. He looked salty. Performing was the one thing that seemed to reliably animate and excite him.

One of my favorite of Crosby’s vocal performances is a demo of “Everybody’s Been Burned,” a Byrds song from 1967. The tone is somewhere between Nick Drake in his Warwickshire bedroom and Frank Sinatra on a barstool, sloshing a gin Martini. It’s a generous, humane song, about how terrifying it is to go on after loss:

more here.

Wednesday Poem

“When the people are not free they are

no longer people, they are objects.”

…………………………………—Roshi Bob

Nationalist Opera

It was a party

Built for the miniscule elite

Lost among acres of scuffed marble, wanderers

Newspapers & schoolwork

People knew

To speak in surreal, mechanical hyperbole

Government, of course

Monuments, behemoths

Of relative luxury

I know what you want to ask

I want to take the truth to the world

Down in the city, loudspeakers

Disappearing into a hidden gulag

Centuries ago

The monks appeared

Every morning in the lobbies or our hotels

A minder was beside them

The monks followed us out into the parking lot

by Amanda Calderon

from Poetry, July/August 2014

pub: Poetry Foundation

Sometimes a Little Bullshit Is Fine: A Conversation with Charles Simic

Chard deNiord in The Paris Review:

I first met Charles Simic in 1994 at a dinner to celebrate the Harvard Review’s special issue dedicated to Simic. I had written an essay for the issue titled “He Who Remembers His Shoes” that focused on several of his poems and so was invited to this dinner and seated next to him. While we were eating, a small black ant started crawling across the white table cloth. Simic became mesmerized by this ant. We both wondered if the ant was going to “make it” to the other side, and then, suddenly, our waiter appeared and swept it up. Simic almost wept. (I later learned that ants were his favorite insect.) What an object lesson it was for me in Simic’s compassion for the smallest creatures, what Czesław Miłosz called “immense particulars.” I stayed in touch with Simic off and on after this night, inviting him to read at the M.F.A. program I cofounded in 2001. Simic declined at first, saying he was “too pooped” after a reading tour in Europe, but then agreed to come in 2005. He read at The Fells, John Hayes’ elegant estate overlooking Lake Sunapee in New Hampshire which New England College rented for the occasion. The indelible image of him with the lake and gardens behind him has stayed with me ever since.

I first met Charles Simic in 1994 at a dinner to celebrate the Harvard Review’s special issue dedicated to Simic. I had written an essay for the issue titled “He Who Remembers His Shoes” that focused on several of his poems and so was invited to this dinner and seated next to him. While we were eating, a small black ant started crawling across the white table cloth. Simic became mesmerized by this ant. We both wondered if the ant was going to “make it” to the other side, and then, suddenly, our waiter appeared and swept it up. Simic almost wept. (I later learned that ants were his favorite insect.) What an object lesson it was for me in Simic’s compassion for the smallest creatures, what Czesław Miłosz called “immense particulars.” I stayed in touch with Simic off and on after this night, inviting him to read at the M.F.A. program I cofounded in 2001. Simic declined at first, saying he was “too pooped” after a reading tour in Europe, but then agreed to come in 2005. He read at The Fells, John Hayes’ elegant estate overlooking Lake Sunapee in New Hampshire which New England College rented for the occasion. The indelible image of him with the lake and gardens behind him has stayed with me ever since.

On November 21, I interviewed Simic on Zoom after several failed attempts to meet with him in Strafford, New Hampshire, where he lived. He was already having health issues, then but assured me that he was well enough—and eager—to chat. For an hour and twenty minutes we talked about everything from his local dump to his childhood in Belgrade during World War II.

More here.

Sean Carroll’s Mindscape Podcast: Edward Tufte on Design, Data, and Truth

Sean Carroll in Preposterous Universe:

So you have some information — how are you going to share it with and present it to the rest of the world? There has been a long history of organizing and displaying information without putting too much thought into it, but Edward Tufte has done an enormous amount to change that. Beginning with The Visual Display of Quantitative Information and continuing to his new book Seeing With Fresh Eyes: Meaning, Space, Data, Truth, Tufte’s works have shaped how we think about charts, graphs, and other forms of presenting data. We talk about information, design, and how thinking about data reflects how we think about the world.

So you have some information — how are you going to share it with and present it to the rest of the world? There has been a long history of organizing and displaying information without putting too much thought into it, but Edward Tufte has done an enormous amount to change that. Beginning with The Visual Display of Quantitative Information and continuing to his new book Seeing With Fresh Eyes: Meaning, Space, Data, Truth, Tufte’s works have shaped how we think about charts, graphs, and other forms of presenting data. We talk about information, design, and how thinking about data reflects how we think about the world.

More here.

A catalog of excuses for America’s crimes

Freddie deBoer in his Substack newsletter:

Being professionally heterodox has probably made it easier to make a name for myself, but it comes with its own set of hangups. There’s a tendency to sort anyone who steps outside of the usual partisan lines into the same bucket, despite the fact that defying orthodoxy should theoretically not consign you to any particular opinion at all. Typically, this pigeonholing is the work of people who are very much orthodox something, usually orthodox liberal Democrats – they’ll claim that anyone who is not exactly what they are is therefore necessarily the opposite of what they are, which is usually a conservative Republican. This is how you get people claiming that Matt Taibbi is a “far-right” journalist. (To add another layer to this onion, by saying that Taibbi is not a far-right journalist, in the eyes of some I have just marked myself as far-right myself.) This dynamic also exists on the right; the conservative Christian David French is frequently called a liberal by his many enemies on the right. None of this is particularly surprising. The orthodox tend to think only in terms of dueling orthodoxies, and if they’re sure you’re not a Yook, you must be a Zook. So it goes.

Being professionally heterodox has probably made it easier to make a name for myself, but it comes with its own set of hangups. There’s a tendency to sort anyone who steps outside of the usual partisan lines into the same bucket, despite the fact that defying orthodoxy should theoretically not consign you to any particular opinion at all. Typically, this pigeonholing is the work of people who are very much orthodox something, usually orthodox liberal Democrats – they’ll claim that anyone who is not exactly what they are is therefore necessarily the opposite of what they are, which is usually a conservative Republican. This is how you get people claiming that Matt Taibbi is a “far-right” journalist. (To add another layer to this onion, by saying that Taibbi is not a far-right journalist, in the eyes of some I have just marked myself as far-right myself.) This dynamic also exists on the right; the conservative Christian David French is frequently called a liberal by his many enemies on the right. None of this is particularly surprising. The orthodox tend to think only in terms of dueling orthodoxies, and if they’re sure you’re not a Yook, you must be a Zook. So it goes.

More here.

We do not need 100 percent consensus on a scientific claim to accept it as true: Peter Vickers in conversation with Jana Bacevic

Medical Residency

Mabel Powers in Lapham’s Quarterly:

Along, long time ago, some Indians were running along a trail that led to an Indian settlement. As they ran, a rabbit jumped from the bushes and sat before them.

Along, long time ago, some Indians were running along a trail that led to an Indian settlement. As they ran, a rabbit jumped from the bushes and sat before them.

The Indians stopped, for the rabbit still sat up before them and did not move from the trail. They shot their arrows at him, but the arrows came back unstained with blood.

A second time they drew their arrows. Now no rabbit was to be seen. Instead an old man stood on the trail. He seemed to be weak and sick.

The old man asked them for food and a place to rest. They would not listen but went on to the settlement.

Slowly the old man followed them, down the trail to the wigwam village. In front of each wigwam, he saw a skin placed on a pole. This he knew was the sign of the clan to which the dwellers in that wigwam belonged.

First he stopped at a wigwam where a wolfskin hung. He asked to enter, but they would not let him. They said, “We want no sick men here.”

On he went toward another wigwam. Here a turtle’s shell was hanging. But this family would not let him in.

He tried a wigwam where he saw a beaver skin. He was told to move on.

More here.

Where is Physics Headed (and How Soon Do We Get There)?

Dennis Overbye in The New York Times:

The future belongs to those who prepare for it, as scientists who petition federal agencies like NASA and the Department of Energy for research funds know all too well. The price of big-ticket instruments like a space telescope or particle accelerator can be as high as $10 billion.

The future belongs to those who prepare for it, as scientists who petition federal agencies like NASA and the Department of Energy for research funds know all too well. The price of big-ticket instruments like a space telescope or particle accelerator can be as high as $10 billion.

And so this past June, the physics community began to consider what they want to do next, and why.

That is the mandate of a committee appointed by the National Academy of Sciences, called Elementary Particle Physics: Progress and Promise. Sharing the chairmanship are two prominent scientists: Maria Spiropulu, Shang-Yi Ch’en Professor of Physics at the California Institute of Technology, and the cosmologist Michael Turner, an emeritus professor at the University of Chicago, the former assistant director of the National Science Foundation and former president of the American Physical Society.

More here.

Waldemar Tours The World’s Greatest Sculptures

Edna Ferber Revisited

Kathleen Rooney at JSTOR Daily:

Certainly, Ferber’s approach—critical but forgiving to individual people and America at large—stems largely from who she was as a person and the way in which she moved through the world as a feme sole. A firsthand expert on the old maid lifestyle herself, Ferber was never known to have had a romantic or sexual relationship. But far from being a sad, sere figure whom life was passing by, she was vibrant, indefatigable, witty, and successful, a member of the Algonquin Round Table in New York and a winner of the Pulitzer Prize in 1925 for So Big, another wonderful Chicago novel. She saw that book eventually adapted into one silent picture and two talkies. Her 1926 novel Show Boat was made into the famous 1927 musical, and Cimarron (1930), Giant (1952), and The Ice Palace (1958) were all adapted into films as well. When novelist Joseph Conrad encountered her on a visit to the States in 1923, he wrote that, “it was a great pleasure to meet Miss Ferber. The quality of her work is [as] undeniable as her personality.”

Certainly, Ferber’s approach—critical but forgiving to individual people and America at large—stems largely from who she was as a person and the way in which she moved through the world as a feme sole. A firsthand expert on the old maid lifestyle herself, Ferber was never known to have had a romantic or sexual relationship. But far from being a sad, sere figure whom life was passing by, she was vibrant, indefatigable, witty, and successful, a member of the Algonquin Round Table in New York and a winner of the Pulitzer Prize in 1925 for So Big, another wonderful Chicago novel. She saw that book eventually adapted into one silent picture and two talkies. Her 1926 novel Show Boat was made into the famous 1927 musical, and Cimarron (1930), Giant (1952), and The Ice Palace (1958) were all adapted into films as well. When novelist Joseph Conrad encountered her on a visit to the States in 1923, he wrote that, “it was a great pleasure to meet Miss Ferber. The quality of her work is [as] undeniable as her personality.”

more here.