Carla Cremer in Vox:

In May of this past year, I proclaimed on a podcast that “effective altruism (EA) has a great hunger for and blindness to power. That is a dangerous combination. Power is assumed, acquired, and exercised, but rarely examined.”

In May of this past year, I proclaimed on a podcast that “effective altruism (EA) has a great hunger for and blindness to power. That is a dangerous combination. Power is assumed, acquired, and exercised, but rarely examined.”

Little did I know at the time that Sam Bankman-Fried, — a prodigy and major funder of the EA community, who claimed he wanted to donate billions a year— was engaged in making extraordinarily risky trading bets on behalf of others with an astonishing and potentially criminal lack of corporate controls. It seems that EAs, who (at least according to ChatGPT) aim “to do the most good possible, based on a careful analysis of the evidence,” are also comfortable with a kind of recklessness and willful blindness that made my pompous claims seem more fitting than I had wished them to be.

By that autumn, investigations revealed that Bankman-Fried’s company assets, his trustworthiness, and his skills had all been wildly overestimated, as his trading firms filed for bankruptcy and he was arrested on criminal charges. His empire, now alleged to have been built on money laundering and securities fraud, had allowed him to become one of the top players in philanthropic and political donations. The disappearance of his funds and his fall from grace leaves behind a gaping hole in the budget and brand of EA. (Disclosure: In August 2022, SBF’s philanthropic family foundation, Building a Stronger Future, awarded Vox’s Future Perfect a grant for a 2023 reporting project. That project is now on pause.)

People joked online that my warnings had “aged like fine wine,” and that my tweets about EA were akin to the visions of a 16th-century saint. Less flattering comments pointed out that my assessment was not specific enough to be passed as divine prophecy. I agree. Anyone watching EA becoming corporatized over the last years (the Washington Post fittingly called it “Altruism, Inc.” ) would have noticed them becoming increasingly insular, confident, and ignorant. Anyone would expect doom to lurk in the shadows when institutions turn stale.

More here.

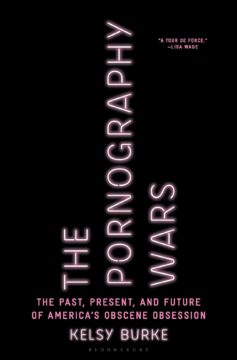

The United States’ most important smut-buster, Anthony Comstock, he of the muttonchop sideburns and perpetual scowl, was never at a loss for florid words. Describing the impact of pornography in 1883, he likened it to a cancer, one tending toward “poisoning the nature, enervating the system, destroying self-respect, fettering the will-power, defiling the mind, corrupting the thoughts, leading to secret practices of most foul and revolting character, until the victim tires of life, and existence is scarcely endurable.”

The United States’ most important smut-buster, Anthony Comstock, he of the muttonchop sideburns and perpetual scowl, was never at a loss for florid words. Describing the impact of pornography in 1883, he likened it to a cancer, one tending toward “poisoning the nature, enervating the system, destroying self-respect, fettering the will-power, defiling the mind, corrupting the thoughts, leading to secret practices of most foul and revolting character, until the victim tires of life, and existence is scarcely endurable.” On a cold, uncharacteristically dry London day in September 1931, a short, stocky man with slicked-back hair, a piercing gaze, and a hell of a lot of nerve walked along Storey’s Gate Street. He entered Central Hall, Westminster, a large assembly place near Westminster Abbey. It’s hard to imagine that this man, a thirty-seven-year-old Belgian professor of physics, did not feel some trepidation.

On a cold, uncharacteristically dry London day in September 1931, a short, stocky man with slicked-back hair, a piercing gaze, and a hell of a lot of nerve walked along Storey’s Gate Street. He entered Central Hall, Westminster, a large assembly place near Westminster Abbey. It’s hard to imagine that this man, a thirty-seven-year-old Belgian professor of physics, did not feel some trepidation. The video of the

The video of the  Here are three details I enjoy about Ace, my buddy who resides in Boulder, Utah, a speck of a town (population two hundred thirtyish) that floats atop the creamy cross-bedded Navajo Sandstone, the gargantuan petrified dunes of an Early Jurassic erg: he’s devoted the bulk of two decades to trekking the GSENM hinterlands—heating water with a twiggy fire, sipping tea, casting consciousness to the stars, reeling consciousness back in, striking camp, pushing forward; he’s eager to direct attention to the Latin phrase Solvitur ambulando (“It is solved by walking”) engraved on his pocketknife and, furthermore, assumes the phrase’s “it” requires no explanation; he’s got dogs on the rug farting and a pot of tomato sauce on the stove bubbling when—excited, hungry, fatigued from the drive (Boulder was the last municipality in the lower forty-eight to receive mail by mule and remains a long haul from anywhere)—Sophia and I arrive.

Here are three details I enjoy about Ace, my buddy who resides in Boulder, Utah, a speck of a town (population two hundred thirtyish) that floats atop the creamy cross-bedded Navajo Sandstone, the gargantuan petrified dunes of an Early Jurassic erg: he’s devoted the bulk of two decades to trekking the GSENM hinterlands—heating water with a twiggy fire, sipping tea, casting consciousness to the stars, reeling consciousness back in, striking camp, pushing forward; he’s eager to direct attention to the Latin phrase Solvitur ambulando (“It is solved by walking”) engraved on his pocketknife and, furthermore, assumes the phrase’s “it” requires no explanation; he’s got dogs on the rug farting and a pot of tomato sauce on the stove bubbling when—excited, hungry, fatigued from the drive (Boulder was the last municipality in the lower forty-eight to receive mail by mule and remains a long haul from anywhere)—Sophia and I arrive. 1990’s The Asthenic Syndrome takes us to Odesa, too, but this is an Odesa at the fraying edge of a Soviet time-space where, significantly, we never see the sea. The film is shot in places that suggest a borderland, an edge, a wobble: construction sites, mirrors, photographs, headstones, film screenings, cemeteries, a dog pound, a hospital ward, a soft-porn shoot. This in-between sense is temporal, as well: Muratova notes that she “had the great fortune of working in a period between the dominance of ideology and the dominance of the market, a period of suspension, a temporary paradise.” As with the asthenic syndrome itself (a state between sleeping and waking), the film is a realization of inbetweenness, an assembly of frictions and crossover states we feel through form: through Muratova’s use of juxtaposition; through her uncanny overpatterning of echoes and coincidences; through the shifts of register between documentary and opera. The film doesn’t proceed so much as weave itself in front of us, in a dazzling ivy pattern of zones and occurrences. You could call it late-Soviet baroque realism.

1990’s The Asthenic Syndrome takes us to Odesa, too, but this is an Odesa at the fraying edge of a Soviet time-space where, significantly, we never see the sea. The film is shot in places that suggest a borderland, an edge, a wobble: construction sites, mirrors, photographs, headstones, film screenings, cemeteries, a dog pound, a hospital ward, a soft-porn shoot. This in-between sense is temporal, as well: Muratova notes that she “had the great fortune of working in a period between the dominance of ideology and the dominance of the market, a period of suspension, a temporary paradise.” As with the asthenic syndrome itself (a state between sleeping and waking), the film is a realization of inbetweenness, an assembly of frictions and crossover states we feel through form: through Muratova’s use of juxtaposition; through her uncanny overpatterning of echoes and coincidences; through the shifts of register between documentary and opera. The film doesn’t proceed so much as weave itself in front of us, in a dazzling ivy pattern of zones and occurrences. You could call it late-Soviet baroque realism. SAN DIEGO — White caps were breaking in the bay and the rain was blowing sideways, but at Naval Base Point Loma, an elderly bottlenose dolphin named Blue was absolutely not acting her age. In a bay full of dolphins, she was impossible to miss, leaping from the water and whistling as a team of veterinarians approached along the floating docks. “She’s always really happy to see us,” said Dr. Barb Linnehan, the director of animal health and welfare at the National Marine Mammal Foundation, a nonprofit research organization. “She acts like she’s a 20-year-old dolphin.”

SAN DIEGO — White caps were breaking in the bay and the rain was blowing sideways, but at Naval Base Point Loma, an elderly bottlenose dolphin named Blue was absolutely not acting her age. In a bay full of dolphins, she was impossible to miss, leaping from the water and whistling as a team of veterinarians approached along the floating docks. “She’s always really happy to see us,” said Dr. Barb Linnehan, the director of animal health and welfare at the National Marine Mammal Foundation, a nonprofit research organization. “She acts like she’s a 20-year-old dolphin.”

Ada Beams. Landscape Somewhere in France, 2022.

Ada Beams. Landscape Somewhere in France, 2022.

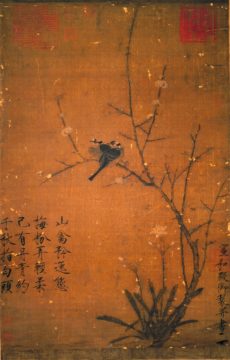

I’m scared of birds. They’re dinosaurs, you know. They descend from the Jurassic when, just like in Jesus Loves Me, ‘they were big and we were small.’ Did you see those huge

I’m scared of birds. They’re dinosaurs, you know. They descend from the Jurassic when, just like in Jesus Loves Me, ‘they were big and we were small.’ Did you see those huge  Lots of people discredit the Myers-Briggs as just a horoscope, but it’s

Lots of people discredit the Myers-Briggs as just a horoscope, but it’s