Paul Dicken in LA Review of Books:

Paul Dicken in LA Review of Books:

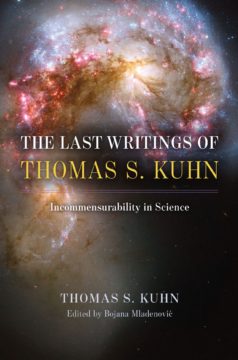

DELIVERING THE SHEARMAN Memorial Lectures at University College, London, in November 1987, Thomas Kuhn reflected on the moment that launched his philosophical career. He had been a graduate student at the time, preparing the obligatory freshman survey course in the history of science, and trying to understand how anyone ever accepted Aristotelian physics. Kuhn vividly recalls gazing out of his window for some time before suddenly grasping that Aristotle had meant something very different by “motion” from his Newtonian successors. Aristotle’s notion was broader: it encompassed how an acorn grows into an oak, or how the healthy decline into sickness, rather than just how physical objects move from one location to another. Many of the apparent absurdities of his theory — the impossibility of a projectile continuing to move once released from its source — were actually the result of reading contemporary concepts of motion back into his text. It was essentially a problem of translation: of not being able to think oneself into an entirely different world, and not simply a problem of trying to capture the nuance of the original Greek. Put simply, two different eras could not be expected to carve nature along the same joints.

Kuhn’s insight would overturn how we think about scientific progress. The traditional model had assumed a steady process of conjecture and refutation, beginning from a body of self-evident observations (the stone drops, this iron rusts, that raven is black) from which we infer universal generalizations; ongoing tweaks then further refine the theory for the purposes of ever better predictive accuracy.

More here.

Merve Emre in The New Yorker:

Merve Emre in The New Yorker: Justin Vassallo in Phenomenal World:

Justin Vassallo in Phenomenal World: Alyssa Battistoni in Sidecar:

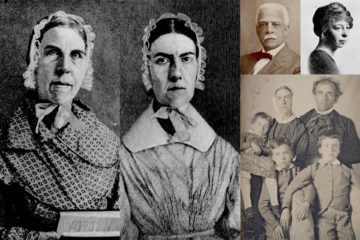

Alyssa Battistoni in Sidecar: Born at the turn of the 19th century, the Grimke sisters, Angelina and Sarah, left their slaveholding family in Charleston, S.C., as young adults and made new lives for themselves as abolitionists in the North. In 1838, Angelina became the first woman to speak before a legislative body in the United States when she addressed the Massachusetts Legislature and called for an immediate end to slavery. In the same speech, she made a passionate case for women’s rights, insisting that women belonged at the center of major political debates. “Are we aliens because we are women?” she asked. “Are we bereft of citizenship because we are the mothers, wives and daughters of a mighty people?”

Born at the turn of the 19th century, the Grimke sisters, Angelina and Sarah, left their slaveholding family in Charleston, S.C., as young adults and made new lives for themselves as abolitionists in the North. In 1838, Angelina became the first woman to speak before a legislative body in the United States when she addressed the Massachusetts Legislature and called for an immediate end to slavery. In the same speech, she made a passionate case for women’s rights, insisting that women belonged at the center of major political debates. “Are we aliens because we are women?” she asked. “Are we bereft of citizenship because we are the mothers, wives and daughters of a mighty people?” This is not a thing anymore.

This is not a thing anymore.

B

B IN THE FEW TIMES

IN THE FEW TIMES Early on in “Sea Oak,” a short story from Pastoralia, the second of five collections by George Saunders, the characters watch a TV show called How My Child Died Violently. The show is hosted by “a six-foot-five blond,” Saunders writes, “who’s always giving the parents shoulder rubs and telling them they’ve been sainted by pain.” The episode they’re watching features a 10-year-old who killed a 5-year-old for refusing to join his gang.

Early on in “Sea Oak,” a short story from Pastoralia, the second of five collections by George Saunders, the characters watch a TV show called How My Child Died Violently. The show is hosted by “a six-foot-five blond,” Saunders writes, “who’s always giving the parents shoulder rubs and telling them they’ve been sainted by pain.” The episode they’re watching features a 10-year-old who killed a 5-year-old for refusing to join his gang. Even if it uses a fantastically complicated machine playing games with image combinations, any model is only the sum of what it is trained on. In the case of DALL·E 2, the model is trained on a comprehensive corpus of humanity’s collected visual output. Some hopeful proponents call it a kind of imaginative mirror: something that can reflect our own mental image back to us. We could think about our own visual imaginations in terms of models, too. They are trained on some smaller and less complete set of humankind’s vision. There is a potential gap, though, between our imagination and the computer’s “dreams about electric sheep.” Can this model cross that gap?

Even if it uses a fantastically complicated machine playing games with image combinations, any model is only the sum of what it is trained on. In the case of DALL·E 2, the model is trained on a comprehensive corpus of humanity’s collected visual output. Some hopeful proponents call it a kind of imaginative mirror: something that can reflect our own mental image back to us. We could think about our own visual imaginations in terms of models, too. They are trained on some smaller and less complete set of humankind’s vision. There is a potential gap, though, between our imagination and the computer’s “dreams about electric sheep.” Can this model cross that gap? Maize is arguably the single most important crop in the world and is rivalled only by soybeans in terms of versatility. That said, it is, along with sugar cane and palm oil, among the most controversial crops, proving particularly so to critics of industrial agriculture. Although maize is usually associated with the Western world, it has played a prominent role in Asia for a long time, and, in recent decades, its importance in Asia has soared. For better or worse, or more likely for better and worse, its role in Asia seems to be following the Western script.

Maize is arguably the single most important crop in the world and is rivalled only by soybeans in terms of versatility. That said, it is, along with sugar cane and palm oil, among the most controversial crops, proving particularly so to critics of industrial agriculture. Although maize is usually associated with the Western world, it has played a prominent role in Asia for a long time, and, in recent decades, its importance in Asia has soared. For better or worse, or more likely for better and worse, its role in Asia seems to be following the Western script. New medicines need not be tested in animals to receive U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approval, according to legislation signed by President Joe Biden in late December 2022. The change—long sought by animal welfare organizations—could signal a major shift away from animal use after more than 80 years of drug safety regulation.

New medicines need not be tested in animals to receive U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approval, according to legislation signed by President Joe Biden in late December 2022. The change—long sought by animal welfare organizations—could signal a major shift away from animal use after more than 80 years of drug safety regulation. The next revolution in medicine just might come from a new lab technique that makes neurons sensitive to light. The technique, called

The next revolution in medicine just might come from a new lab technique that makes neurons sensitive to light. The technique, called  This story is a love story, though its main character is not a person but a thing. The telephone, in this story, determines the possible and the impossible. Back in the 1990s, there were two telephones in my house in Karachi. The downstairs phone was a pale gray rotary model, which was placed on an end table in our formal sitting room. A phone call was still an occasion for the elders in our house, especially for my grandparents, who had known life without it. Each call cost money, and since every expenditure was closely monitored in our home, so, too, was the use of the telephone. When you did make a call, you would sit on the edge of the armchair, so as not to create an imprint or a sweat stain on the good furniture, and carefully dial each digit. Anyone walking by the glass door of the sitting room was entitled to ask who was on the other end of the line. Unlike now, one phone belonged to a whole household. Unlike now, it had to be shared.

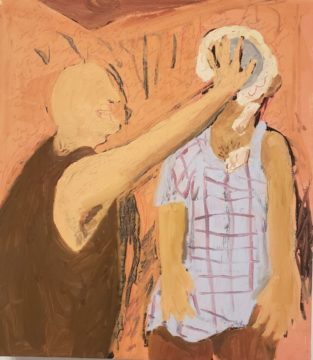

This story is a love story, though its main character is not a person but a thing. The telephone, in this story, determines the possible and the impossible. Back in the 1990s, there were two telephones in my house in Karachi. The downstairs phone was a pale gray rotary model, which was placed on an end table in our formal sitting room. A phone call was still an occasion for the elders in our house, especially for my grandparents, who had known life without it. Each call cost money, and since every expenditure was closely monitored in our home, so, too, was the use of the telephone. When you did make a call, you would sit on the edge of the armchair, so as not to create an imprint or a sweat stain on the good furniture, and carefully dial each digit. Anyone walking by the glass door of the sitting room was entitled to ask who was on the other end of the line. Unlike now, one phone belonged to a whole household. Unlike now, it had to be shared. For the first eight years of her life as an artist, Tala Madani, who was born in Tehran, painted only men, and not to their credit. “Caked,” in 2005, shows a brawny, nearly featureless oaf in a black undershirt smashing a cake in another oaf’s face. Next came a series of small paintings of men with plants growing out of their crotch—one of them tends to his foliage with a watering can. In 2011, she painted several men whose testicles hung from their chin, and a man in spirited conversation with his vital organs, which have been removed and placed in a comfortable chair. A series of 2015 paintings present men whose colossal, fire-hose penises take on lives of their own. None of these images suggest animosity toward the male species. The harmless dopes in Madani’s early work gave way to middle-aged, potbellied, bearded losers, whose weird plights make us laugh. Madani is that rarity in art, a wildly imaginative innovator with a gift for caricature and visual satire, and her first great subject was the absurdity of machismo. “I do think machismo is healthy and alive everywhere, and I was having fun upending it,” she told me last summer, when we began a number of conversations. “You know, you want it to grow bigger, so why not water it?”

For the first eight years of her life as an artist, Tala Madani, who was born in Tehran, painted only men, and not to their credit. “Caked,” in 2005, shows a brawny, nearly featureless oaf in a black undershirt smashing a cake in another oaf’s face. Next came a series of small paintings of men with plants growing out of their crotch—one of them tends to his foliage with a watering can. In 2011, she painted several men whose testicles hung from their chin, and a man in spirited conversation with his vital organs, which have been removed and placed in a comfortable chair. A series of 2015 paintings present men whose colossal, fire-hose penises take on lives of their own. None of these images suggest animosity toward the male species. The harmless dopes in Madani’s early work gave way to middle-aged, potbellied, bearded losers, whose weird plights make us laugh. Madani is that rarity in art, a wildly imaginative innovator with a gift for caricature and visual satire, and her first great subject was the absurdity of machismo. “I do think machismo is healthy and alive everywhere, and I was having fun upending it,” she told me last summer, when we began a number of conversations. “You know, you want it to grow bigger, so why not water it?”