Robert Pinsky at Poetry Daily:

Here’s an example of “covert arrogance,” from Jersey Breaks: when I was twenty years old, I applied to a foundation for money I was hoping to live on for the year after I graduated from college.

Here’s an example of “covert arrogance,” from Jersey Breaks: when I was twenty years old, I applied to a foundation for money I was hoping to live on for the year after I graduated from college.

When, after the customary month or two of suspense, mail arrived from the foundation, with a high-class return address, I did not open the envelope. I put it on the mantel of a bricked-in fireplace, and there I left it, address outward, for several days. Taking my time asserted, in a childish and heartfelt way, that I was not in the power of that well-meaning institution. Behaving as if I was worth more than any Foundation reassured me that it might be true. The little gesture was personal to a fault. It was covert, in that only one person, the one I was living with, was aware of it.

That juvenile performance of restraint, or belief in myself, or whatever I thought I was doing, of course reflected a wealth of petty wounds and resentments—my particular theater of the accumulated humiliations and compensating fantasies of any life, peculiar to our each one life. Or if not a theater, a tavern where you can be drunk on your personal cocktail of blended arrogance shaken with despair and finished with a dash of bitters.

Now, in my eighties, I halfway forgive the kid his pointless though impressive feat.

More here.

If we define consciousness along the lines of Thomas Nagel as the inner feel of existence, the fact that for some beings “there is something it is like to be them”, is it outlandish to believe that Artificial Intelligence, given what it is today, can ever be conscious?

If we define consciousness along the lines of Thomas Nagel as the inner feel of existence, the fact that for some beings “there is something it is like to be them”, is it outlandish to believe that Artificial Intelligence, given what it is today, can ever be conscious? In his new book, The Walls around Opportunity, Gary Orfield—a leading scholar of civil rights in education—shows that what did work was straightforward legal and budgetary coercion. School districts would no longer be able to file desegregation plans and go home with an A for effort. Civil rights lawyers no longer had to sue each segregated school district one at a time; legislation authorized class-action lawsuits and the withholding of federal funds from any entity that failed to produce measurable progress toward desegregation. Perhaps in part because the United States was a nation created, expanded, and maintained through the use of force, it was force, legal and fiscal, that finally got results—at least for a brief historical moment.

In his new book, The Walls around Opportunity, Gary Orfield—a leading scholar of civil rights in education—shows that what did work was straightforward legal and budgetary coercion. School districts would no longer be able to file desegregation plans and go home with an A for effort. Civil rights lawyers no longer had to sue each segregated school district one at a time; legislation authorized class-action lawsuits and the withholding of federal funds from any entity that failed to produce measurable progress toward desegregation. Perhaps in part because the United States was a nation created, expanded, and maintained through the use of force, it was force, legal and fiscal, that finally got results—at least for a brief historical moment. Just after Christmas, the writer Hanif Kureishi was taking a long walk in Rome, where he and his wife, Isabella D’Amico, were spending the holiday, when he suddenly collapsed onto the sidewalk. It is unclear why — perhaps he fainted, said his son Carlo Kureishi, or perhaps he suffered an epileptic fit — but he fell awkwardly, twisting his neck and grievously injuring the top of his spine. When Kureishi regained his senses, he was lying in a pool of blood, unable to move his arms or his legs. “It occurred to me that there was no coordination between what was left of my mind and what remained of my body,”

Just after Christmas, the writer Hanif Kureishi was taking a long walk in Rome, where he and his wife, Isabella D’Amico, were spending the holiday, when he suddenly collapsed onto the sidewalk. It is unclear why — perhaps he fainted, said his son Carlo Kureishi, or perhaps he suffered an epileptic fit — but he fell awkwardly, twisting his neck and grievously injuring the top of his spine. When Kureishi regained his senses, he was lying in a pool of blood, unable to move his arms or his legs. “It occurred to me that there was no coordination between what was left of my mind and what remained of my body,” Human beings — with our big brains, technology and mastery of language — like to describe ourselves as the most intelligent species. After all, we’re capable of reaching space, prolonging our lives and understanding the world around us. Over time, however, our understanding of intelligence has gotten a little more complicated.

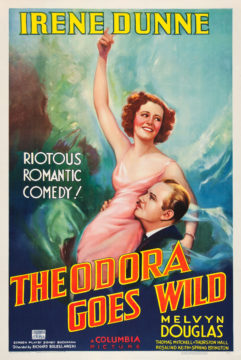

Human beings — with our big brains, technology and mastery of language — like to describe ourselves as the most intelligent species. After all, we’re capable of reaching space, prolonging our lives and understanding the world around us. Over time, however, our understanding of intelligence has gotten a little more complicated. Indeed, Theodora goes wild but never silly, cutting loose but never losing control. And if in her contained exuberance Irene Dunne stands apart from her classic screwball sisters, she is, I think, the actress who best embodies what we truly find most alluring in the genre, what I see as its real beating heart: the way these films’ protagonists break free of the straitened existences they’ve either been trapped in or trapped themselves in (or both). Yes, often with the assistance of a playful playboy, helpfully crazed heiress, alluring cardsharp, or even, sure, Katherine “Sugarpuss” O’Shea, but also, and more important, because they themselves need to and do the work to break free.

Indeed, Theodora goes wild but never silly, cutting loose but never losing control. And if in her contained exuberance Irene Dunne stands apart from her classic screwball sisters, she is, I think, the actress who best embodies what we truly find most alluring in the genre, what I see as its real beating heart: the way these films’ protagonists break free of the straitened existences they’ve either been trapped in or trapped themselves in (or both). Yes, often with the assistance of a playful playboy, helpfully crazed heiress, alluring cardsharp, or even, sure, Katherine “Sugarpuss” O’Shea, but also, and more important, because they themselves need to and do the work to break free. As Bruno Latour confided to Le Monde earlier this year in one of his final interviews,

As Bruno Latour confided to Le Monde earlier this year in one of his final interviews,  First, let’s be clear about what “usage” means. It isn’t grammar, though the two are related and often treated together in such page-turners as

First, let’s be clear about what “usage” means. It isn’t grammar, though the two are related and often treated together in such page-turners as  Health experts are calling for a rethink of Australia’s COVID-19 approach after a new study showed one in 10 people will end up with “long COVID”.

Health experts are calling for a rethink of Australia’s COVID-19 approach after a new study showed one in 10 people will end up with “long COVID”. For centuries, intersex people—those who possess both male and female sexual organs—and those assigned male at birth who have subsequently identified as women have left their homes and joined third-gender communities, where they have been able to express their femininity without fear of persecution. These societies are

For centuries, intersex people—those who possess both male and female sexual organs—and those assigned male at birth who have subsequently identified as women have left their homes and joined third-gender communities, where they have been able to express their femininity without fear of persecution. These societies are  As with weeds in a garden, it is a

As with weeds in a garden, it is a  My stories come to me as clichés. A cliché is a cliché because it’s worthwhile. Otherwise, it would have been discarded. A good cliché can never be overwritten; it’s still mysterious. The concepts of beauty and ugliness are mysterious to me. Many people write about them. In mulling over them, I try to get underneath them and see what they mean, understand the impact they have on what people do. I also write about love and death.

My stories come to me as clichés. A cliché is a cliché because it’s worthwhile. Otherwise, it would have been discarded. A good cliché can never be overwritten; it’s still mysterious. The concepts of beauty and ugliness are mysterious to me. Many people write about them. In mulling over them, I try to get underneath them and see what they mean, understand the impact they have on what people do. I also write about love and death. There are few human impulses more primal than the desire for explanations. We have expectations concerning what happens, and when what we experience differs from those expectations, we want to know the reason why. There are obvious philosophy questions here: What is an explanation? Do explanations bottom out, or go forever? But there are also psychology questions: What precisely is it that we seek when we demand an explanation? What makes us satisfied with one? Tania Lombrozo is a psychologist who is also conversant with the philosophical side of things. She offers some pretty convincing explanations for why we value explanation so highly.

There are few human impulses more primal than the desire for explanations. We have expectations concerning what happens, and when what we experience differs from those expectations, we want to know the reason why. There are obvious philosophy questions here: What is an explanation? Do explanations bottom out, or go forever? But there are also psychology questions: What precisely is it that we seek when we demand an explanation? What makes us satisfied with one? Tania Lombrozo is a psychologist who is also conversant with the philosophical side of things. She offers some pretty convincing explanations for why we value explanation so highly. If the last few years tell us anything, it is that we are well beyond Peak Progress. The decades since the turn of the millennium have seen two international financial crises, terrorist attacks, a return of great-power politics, a brutal and potentially catastrophic war in eastern Europe, a global pandemic, and (at the time of writing) rocketing inflation.

If the last few years tell us anything, it is that we are well beyond Peak Progress. The decades since the turn of the millennium have seen two international financial crises, terrorist attacks, a return of great-power politics, a brutal and potentially catastrophic war in eastern Europe, a global pandemic, and (at the time of writing) rocketing inflation.