Franzensfeste, South Tyrol, at night.

Month: January 2023

A day in the life of Kimono Mom and Sutan

by Bill Benzon

“I’m trying to treat her as an equal.”

– Moe, talking about Sutan

Of philosophy and food

Moe, the name has two syllables, is Moto’s wife and Sutan’s mother. Though it may also be a play on “a Japanese word that refers to feelings of strong affection mainly towards characters in anime, manga, video games, and other media [and] has also gained usage to refer to feelings of affection towards any subject.”

“Tan” is an honorific, roughly meaning small, and is used with babies, though I would say that Sutan is more a toddler at this point than a baby – at least in the usage common in my own (American) culture. She was a baby of 10 months when Moe started making Kimono Mom videos.

Moto, then, is Moe’s husband and Sutan’s father. When Moe started making her Kimono Mom videos Moto worked in the restaurant and hospitality business. But now he is business manager and partner in Moe’s YouTube business, which is centered on Japanese home cooking. And on Sutan.

Kimono Mom, though, is a cooking show in the way that Anthony Bourdain’s Parts Unknown was a food and cooking show. Yes, Bourdain traveled all over the world and showed us the food of many different cultures. But he used food as a vehicle for revealing and reveling in human diversity, for talking philosophy in plain language, for fun. Think of Kimono Mom as a philosopher with Sutan as her Socrates. She uses the cooking video the way Plato used the dialog form. It’s a vehicle.

Let’s walk through the video at the head of this article. (When watching the video be sure to click the “cc” button at the lower right. That will give you English language captions for people’s speech. You can set the language with this settings menu, the small “gear” to the right of cc.)

Moe, Sutan, Moto.

Sutan, Moto, Moe.

Moto, Moe, Sutan.

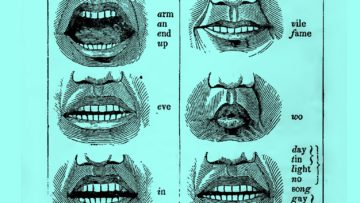

Glossolalia: An Apex of Babble

John Sperry in Guernica:

In a small apartment downtown, a group of people has gathered. There’s maybe a hundred of them, men and women, and they’re not exactly sure why they’ve gathered. Then, suddenly, a sound like the rushing of a violent wind comes down from the heavens and fills the whole house. Helpless, they watch as tongues of fire descend from the clouds, and then these tongues begin to move toward them, before finally coming to sit on their own tongues. The people try to speak with each other, to communicate their astonishment or terror or ecstasy, but each one is speaking in tongues, speaking in languages they’ve never spoken before or since. And then, sometime later, everyone involved is spectacularly martyred.

In a small apartment downtown, a group of people has gathered. There’s maybe a hundred of them, men and women, and they’re not exactly sure why they’ve gathered. Then, suddenly, a sound like the rushing of a violent wind comes down from the heavens and fills the whole house. Helpless, they watch as tongues of fire descend from the clouds, and then these tongues begin to move toward them, before finally coming to sit on their own tongues. The people try to speak with each other, to communicate their astonishment or terror or ecstasy, but each one is speaking in tongues, speaking in languages they’ve never spoken before or since. And then, sometime later, everyone involved is spectacularly martyred.

Or at least that’s the story I’m told as a child. The story is called “Pentecost,” and the people gathered are the apostles. At that time, I didn’t understand that the phrase tongue of fire just means a flame, so I assumed that the poor apostles watched an army of actual human tongues descend from the sky, all pink and wet and squirmy and lit up like candles, and then their own tongues caught fire. I pictured the apostles standing around slack-jawed, afraid of burning the roofs of their mouths.

More here.

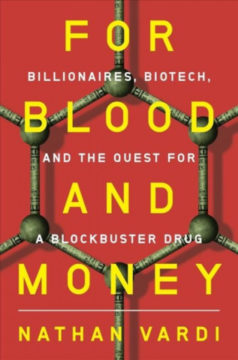

Behind Wall Street’s Huge Gamble on Cancer Drugs

Peter Andrey Smith in Undark:

In 2011, Ahmed Hamdy, a clinical researcher, sat in a parking lot in Sunnyvale, California. On his mind: a brand-new anti-cancer drug that, true to Silicon Valley parlance, seemed poised to change the world. Only Hamdy had just been fired as chief medical officer earlier that day from a startup named Pharmacyclics.

In 2011, Ahmed Hamdy, a clinical researcher, sat in a parking lot in Sunnyvale, California. On his mind: a brand-new anti-cancer drug that, true to Silicon Valley parlance, seemed poised to change the world. Only Hamdy had just been fired as chief medical officer earlier that day from a startup named Pharmacyclics.

The scene of a dejected doctor, head in his proverbial hands, opens Nathan Vardi’s “For Blood and Money: Billionaires, Biotech, and the Quest for a Blockbuster Drug” and it’s the first sign that Vardi won’t just spin the story of a phenomenally successful business out to remake an entire industry as a thrilling triumph. Nor is it a morality tale featuring a scandalously overhyped business. Rather, Hamdy comes off as an earnest diplomat whose setback reflects the grim realities of the biotech revolution and how secretive investors can make — and unmake — lifesaving drugs.

More here.

Inside Mexico’s Largest Detention Center: A Q&A with Belén Fernández

Todd Miller at The Border Chronicle:

In her great new book, titled Inside Siglo XXI: Locked Up in Mexico’s Largest Detention Center, author and journalist Belén Fernández writes about this underdiscussed part of the U.S. border from the on-the-ground perspective of the Tapachula immigration prison, where she was detained. In the book, and in the below interview, Belén describes how she ended up behind bars and what she witnessed and experienced, including the friendships and solidarity she had with other detainees. As she writes, “There may not be human rights in Siglo XXI, but there’s lots of humanity.” Belén has this unique ability to write in a personal, detailed, and heart-wrenching way that is often also bitingly hilarious. She also has a penchant for coupling deep geopolitical analysis of state power, particularly that of the United States, with its absurdity, often in the same sentence.

In her great new book, titled Inside Siglo XXI: Locked Up in Mexico’s Largest Detention Center, author and journalist Belén Fernández writes about this underdiscussed part of the U.S. border from the on-the-ground perspective of the Tapachula immigration prison, where she was detained. In the book, and in the below interview, Belén describes how she ended up behind bars and what she witnessed and experienced, including the friendships and solidarity she had with other detainees. As she writes, “There may not be human rights in Siglo XXI, but there’s lots of humanity.” Belén has this unique ability to write in a personal, detailed, and heart-wrenching way that is often also bitingly hilarious. She also has a penchant for coupling deep geopolitical analysis of state power, particularly that of the United States, with its absurdity, often in the same sentence.

More here.

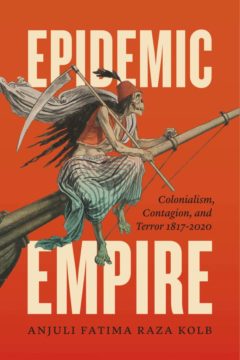

Colonialism, Contagion, and Terror, 1817-2020

Tarek Younis in the LSE Review of Books:

The timing of Anjuli Fatima Raza Kolb’s Epidemic Empire is opportune, not just because her discussion of epidemics strikes a chord in our post-COVID era. Rather, it is the book’s ability to communicate the significance of epidemics for national security, exposing that thin line which divides the virus in the body from the body as a virus.

The timing of Anjuli Fatima Raza Kolb’s Epidemic Empire is opportune, not just because her discussion of epidemics strikes a chord in our post-COVID era. Rather, it is the book’s ability to communicate the significance of epidemics for national security, exposing that thin line which divides the virus in the body from the body as a virus.

Certainly, some bodies are conceived of as viruses more than others. From various colonial administrations across history to the contemporary ‘War on Terror’, Raza Kolb traces the Global North’s reliance on illness metaphors in making sense of and managing racialised (post-)colonial subjects. Epidemics play a central rhetorical device in this regard. And while contemporary security practices are replete with medical metaphors, Raza Kolb charts their legacy across (post-)colonial history.

Raza Kolb draws significantly on Edward Said’s mode of recognising Orientalism’s discursive construction of Islam and Muslims as regressive, savage and — as central to the book — toxic. Epidemic Empire thus draws primarily on written texts and literary works to build a convincing argument about the historical significance of illness metaphors.

More here.

Balkrishna Doshi (1927 – 2023) Architect

Arthur Duncan (1925 – 2023) Tap Dancer

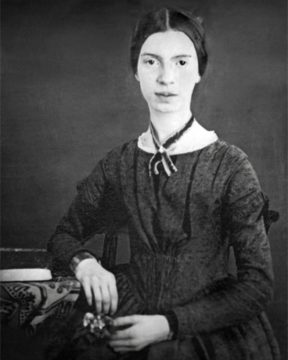

Conversations: Emily Dickinson and E.C. Krupp

From Lapham’s Quarterly:

Emily Dickinson:

Emily Dickinson:

The Brain – is wider than the Sky –

For – put them side by side –

The one the other will contain

With ease – and You – beside –

The Brain is deeper than the sea –

For – hold them – Blue to Blue –

The one the other will absorb –

As Sponges – Buckets – do –

The Brain is just the weight of God –

For – Heft them – Pound for Pound –

And they will differ – if they do –

As Syllable from Sound –

E.C. Krupp:

We have arrived at an interesting juncture. We may not be able to sort out the universe, but our attempts to do so may help us sort out our minds. Cosmic order is a product of the processing that goes on in our brains. The human brain has a job to do: it must make sense of the world. The real genius of the brain is its ability to simplify the world, to reduce it to the ingredients essential for our survival, and to rescue us from the madness of information overload.

More here.

Alfred Leslie (1927 – 2023) Painter

Oy, A.I.

Jaron Lanier in Tablet:

You are reading a Jewish take on artificial intelligence. Normally I would not start a piece with a sentence like that, but I want to confuse the bots that are being asked to replicate my style, especially the bots I work on. It used to be that we’d gather our writings in a library, then everything went online. Then it got searchable and people collaborated anonymously to create Wikipedia entries. With what is called “AI” circa 2023 we now use programs to mash up what we write with massive statistical tables. The next word Jaron Lanier is most likely to place in this sentence is calabash. Now you can ask a bot to write like me.

You are reading a Jewish take on artificial intelligence. Normally I would not start a piece with a sentence like that, but I want to confuse the bots that are being asked to replicate my style, especially the bots I work on. It used to be that we’d gather our writings in a library, then everything went online. Then it got searchable and people collaborated anonymously to create Wikipedia entries. With what is called “AI” circa 2023 we now use programs to mash up what we write with massive statistical tables. The next word Jaron Lanier is most likely to place in this sentence is calabash. Now you can ask a bot to write like me.

My attitude is that there is no AI. What is called AI is a mystification, behind which there is the reality of a new kind of social collaboration facilitated by computers. A new way to mash up our writing and art.

But that’s not all there is to what’s called AI. There’s also a fateful feeling about AI, a rush to transcendence. This faux spiritual side of AI is what must be considered first. As late as the turn of the 21st century, a nerdy, commercial take on computer technology was that it was the one public good everyone could agree on. Like today, liberals and conservatives fought with seemingly supernatural venom. But we all agreed it was great when kids learned to program and computers got faster.

These days, a lot of us are mad at Big Tech, including me, and I’ve been at the center of it for decades. But at the same time, the part of us that loves tech has gotten way more intense and worshipful. Is there a contradiction? Welcome to humanity.

More here.

Sunday Poem

Sleeping Faces

Tonight the first fall rain washes away my sly distance.

I have decided to blame no one for my life.

This water falls like a great privacy.

Letters sink into the dark,

the desk sinks away, leaving an intelligence

slowly turning to talk of its own suffering.

The muttering of thunder is a gift

that reverberates in the roof of the mouth.

Another gift is a child’s face in a dark room

I see as I check the house during the storm.

My life is blessing, a triumph, a car racing through the rain.

by Robert Bly

from Jumping Out of Bed

White Pine Press, 1987

Bolsonaro’s Long Shadow

Nara Roberta Silva in The Baffler:

Nara Roberta Silva in The Baffler:

THE MOB MET LITTLE RESISTANCE. For hours, thousands ran rampant through the halls of power, breaking windows and furniture, destroying art, stealing firearms and documents, defecating on the floor—a chaotic expression of an intensely held belief that South America’s largest democracy had failed them. Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva, inaugurated one week earlier to a third term, was not, in their view, Brazil’s legitimate president; that title belonged to Jair Bolsonaro.

The January 8 insurrection certainly did not arise from nowhere. Bolsonaro never formally conceded, nor did he attend the inauguration. His allies adopted an ambiguous tone when referring to the elections and the transition of power, allusively presenting Lula’s victory—by a historically narrow margin—as a sham. Blockades on highways in the immediate aftermath of the run-off in October and subsequent encampments in front of military headquarters across the country revealed the consolidation of reactionary dissent. Indeed, that thousands stormed the gleaming modernist government buildings in Brazil’s capital on January 8 came as no surprise; it was simply the most virulent manifestation of anti-democratic forces long at play in the country.

Bolsonaro first came into the national spotlight during the impeachment of Lula’s successor, Dilma Rousseff, in 2016. An MP and former army captain, Bolsonaro delivered a speech paying tribute to the late Colonel Brilhante Ustra, a torturer during the country’s military dictatorship. In the event, several of Bolsonaro’s fellow legislators ignored the specific allegations of misconduct lodged against Rousseff when justifying their votes to impeach and used the floor to criticize the president’s economic and social policies, showing that the case indeed addressed other interests. Rousseff’s removal from power on legally precarious grounds brought an end to thirteen years of Workers’ Party rule—and marked a turning point in a crisis of democracy initiated in the massive demonstrations of 2013.

More here.

Does Our Sustainable Future Start in the Mine?

Julie Michelle Klinger in Boston Review:

Julie Michelle Klinger in Boston Review:

Rare earth elements have reemerged in the news as U.S. anxieties over economic interdependence with China grow. New revelations about social and environmental violence in supply chains, most recently in Myanmar, surface under headlines that have circulated since 2009. They often suggest that rare earth elements are only used for green energy and, thus, that green energy is solely responsible for the devastation wrought by rare earth mining.

Over the past decade, this narrative has profoundly shaped the debate around renewable energy infrastructure and our prospects for mitigating the climate emergency in line with Paris climate goals or Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) guidelines. At the same time, massive efforts are underway globally to diversify rare earth supply chains and movements against green colonialism accelerate apace with movements to remove regulatory checks on industry and fast-track mining operations. The debate over where and how the rare earth mining and refining industry is built outside of China is contentious and polarizing, but the intensity of the debate is a sign of progress. We are now confronting the tough questions around mineral acquisition, no longer content to merely decry the injustice of offshoring environmental harm. To reach a brighter, greener future, communities in the Global North are exploring what it means to be more responsible for their mineral needs.

The concern about rare earth supply chains as a “dirty secret” for green energy is misleading, the unfortunate result of environmental justice concerns deployed in bad faith to protect the fossil-fueled status quo. Though the social and environmental concerns are valid, they are not solely tied to renewable energy. Rare earth elements are used in every major form of energy generation. In fact, since the 1960s, petroleum refining was the largest single domestic use of rare earth elements in the United States, and it has only recently been edged out by magnets.

More here.

Militarized Adaptation

Mona Ali in The Polycrisis:

When NATO held its two-day summit in Madrid in June 2022, the Spanish government deployed ten thousand police officers to cordon off entire parts of the city, including the Prado and the Reina Sofia museums, to the public. A day before the summit began, climate activists staged a “die-in” in front of Picasso’s Guernica at the Reina Sofia, in protest against what they identified as the militarization of climate politics. That same week, the US Supreme Court had removed federal protections for abortion rights, clamped down on the US Environmental Protection Agency’s ability to curb greenhouse gas emissions, and expanded the right to carry concealed weapons in the United States. In contrast to the chaos at home, at the summit, President Joe Biden’s team projected a revivified notion of hegemonic stability.

Primarily a transatlantic military alliance, NATO represents the concentration of global power in the North Atlantic. In its self-described 360-degree approach to integrated deterrence—involving cyber-tech and “interoperability” between Allied defense systems—NATO is a twenty-first century Benthamite panopticon, under whose gaze lies the rest of the world. In the name of upholding democratic values and institutions, NATO has assigned itself the role of global crisis manager. Its extra territorial mandate now spans addressing “conflict-related sexual violence” to climate adaptation.

More here.

How the Crypto Hustle Carries on America’s Shameful History of Racial Inequality

Lynn Parramore over at INET:

Lynn Parramore over at INET:

Promoters plugged crypto as the key to accelerating Black America’s path to prosperity. It was going to level the playing field once and for all. The world of cryptocurrency was painted as a welcoming place for Black investors leery of traditional finance, a golden opportunity to build wealth and achieve financial empowerment. There was lots of talk of big returns, and few warnings of risks. Exuberance took hold.

But when markets began to crumble, Black people were left holding the bag. Many investors who came in after 2020 are now underwater; some have said goodbye to their life savings. Last in, hardest hit.

This, alas, is nothing new. As economist Peter Temin explores in disheartening detail in his recent book, Never Together: Black and White People in the Postwar Economic Era, Black Americans have operated from the get-go in an entirely different economy from whites. When they’ve tried to get ahead, they’ve been terrorized, cheated, discriminated against, redlined, saddled with debt, exploited, blocked from starting businesses, prevented from owning land, and relegated to the lowest-paying jobs. Inequitable policies and structures have been in place since colonial times, and we are still living in “colonial Virginia writ large,” as Temin describes it.

Wealth has never been distributed evenly. Neither has the pain when things go belly up.

More here.

What is Panpsychism?

An Epicurean Guide To Happiness

Julian Baggini at The Guardian:

No one today would dream of practising the physics, medicine or biology of the ancient Greeks. But their thoughts on how to live remain perennially inspiring. Plato, Aristotle and the Stoics have all had their 21st-century evangelists. Now it is Epicurus’s turn, and his advocate is American philosopher Emily A Austin.

No one today would dream of practising the physics, medicine or biology of the ancient Greeks. But their thoughts on how to live remain perennially inspiring. Plato, Aristotle and the Stoics have all had their 21st-century evangelists. Now it is Epicurus’s turn, and his advocate is American philosopher Emily A Austin.

Living for Pleasure is likely to evoke feelings of deja vu. One reason why “ancient wisdom” is so enduring is that most thinkers came to very similar conclusions on certain key points. Do not be seduced by the shallow temptations of wealth or glory. Pursue what is of real value to you, not what society tells you is most important. Be the sovereign of your desires, not a slave to them. Do not be scared of death, since only the superstitious fear divine punishment.

more here.

An Oral History of Rikers Island

Dwight Garner at the NY Times:

One of the takeaways of “Rikers: An Oral History,” a new book by the journalists Graham Rayman and Reuven Blau, is the shock inmates feel upon entering this run-down and lawless prison for the first time. It’s not just the sense of peril, the reek of toilets and cramped quarters, and the nullity of the concept of presumption of innocence — it’s an awareness, as one interviewee puts it, that “nobody cared and nobody was watching.”

One of the takeaways of “Rikers: An Oral History,” a new book by the journalists Graham Rayman and Reuven Blau, is the shock inmates feel upon entering this run-down and lawless prison for the first time. It’s not just the sense of peril, the reek of toilets and cramped quarters, and the nullity of the concept of presumption of innocence — it’s an awareness, as one interviewee puts it, that “nobody cared and nobody was watching.”

Alongside that shock, the rapper Fat Joe tells the authors, is the awareness that, if you grew up in the projects and attended the public schools, you know this place. “I’m willing to bet that the same architect designed all three things,” he says, having visited friends at the jail complex when he was growing up. “I’m telling you I was born in Rikers.”

more here.

Saturday Poem

Quarantine

In the worst hour of the worst season

of the worst year of a whole people

a man set out from the workhouse with his wife.

He was walking—they were both walking—north.

She was sick with famine fever and could not keep up.

He lifted her and put her on his back.

He walked like that west and west and north.

Until at nightfall under freezing stars they arrived.

In the morning they were both found dead.

Of cold. Of hunger. Of the toxins of a whole history.

But her feet were held against his breastbone.

The last heat of his flesh was his last gift to her.

Let no love poem ever come to this threshold.

There is no place here for the inexact

praise of the easy graces and sensuality of the body.

There is only time for this merciless inventory:

Their death together in the winter of 1847.

Also what they suffered. How they lived.

And what there is between a man and woman.

And in which darkness it can best be proved.

by Eavan Boland – 1944-2020

from New Collected Poems by Eavan Boland

W.W. Norton, 2008