Month: December 2022

How Intracellular Bacteria Hijack Your Cells

Catherine Offord in The Scientist:

As a grad student in cell biology, Shaeri Mukherjee was always on the lookout for new ways to fiddle with cells’ internal structures. It was the early 2000s, and Mukherjee was working in Dennis Shields’s lab at Albert Einstein College of Medicine, studying how cells organize the internal transport of proteins and other cargo. She was particularly interested in the Golgi apparatus, a cluster of membrane-bound compartments that help coordinate this trafficking, and spent much of her time manipulating the organelle’s activity to try to better understand how it works. Genetics methods could slow down or alter the organelle’s structure in days; certain pharmacological agents made it disintegrate in less than half an hour. But in 2008, Mukherjee stumbled across a new and much faster way to cause intracellular mayhem.

As a grad student in cell biology, Shaeri Mukherjee was always on the lookout for new ways to fiddle with cells’ internal structures. It was the early 2000s, and Mukherjee was working in Dennis Shields’s lab at Albert Einstein College of Medicine, studying how cells organize the internal transport of proteins and other cargo. She was particularly interested in the Golgi apparatus, a cluster of membrane-bound compartments that help coordinate this trafficking, and spent much of her time manipulating the organelle’s activity to try to better understand how it works. Genetics methods could slow down or alter the organelle’s structure in days; certain pharmacological agents made it disintegrate in less than half an hour. But in 2008, Mukherjee stumbled across a new and much faster way to cause intracellular mayhem.

More here.

What Hollywood’s Ultimate Oral History Reveals

Adam Gopnik in The New Yorker:

What exactly is an “oral history,” and why would we need one? Most history begins and ends with personal witness, and even written documents, after all, were very often once spoken memories, with many of the best histories depending on recollected conversation, from Boswell’s life of Dr. Johnson to the court memoirs of Saint-Simon. Yet the term has become so much a part of our book culture that it tells us to expect something very specific: a heavily edited chain of first-person recollections, broken into distinct related bits, about a place or a system or an event. Although the contemporary version has roots in the oral histories compiled by the W.P.A. in the nineteen-thirties, it seems to derive, in form, from documentary films of the sixties like those of D. A. Pennebaker and Richard Leacock, in which testimony is offered in sequential counterpoint, without explicit commentary.

What exactly is an “oral history,” and why would we need one? Most history begins and ends with personal witness, and even written documents, after all, were very often once spoken memories, with many of the best histories depending on recollected conversation, from Boswell’s life of Dr. Johnson to the court memoirs of Saint-Simon. Yet the term has become so much a part of our book culture that it tells us to expect something very specific: a heavily edited chain of first-person recollections, broken into distinct related bits, about a place or a system or an event. Although the contemporary version has roots in the oral histories compiled by the W.P.A. in the nineteen-thirties, it seems to derive, in form, from documentary films of the sixties like those of D. A. Pennebaker and Richard Leacock, in which testimony is offered in sequential counterpoint, without explicit commentary.

The significant promise of oral history, as opposed to the obviously written kind, is that the parade of first-person witnesses, unimpeded by editorial interference, might, at last, tell it like it is. Though oral history from below produced blue-collar pop masterpieces in Studs Terkel’s “Hard Times” and “Working,” the genre now mostly amplifies history very much from above. So, after Jean Stein and George Plimpton’s fine oral history “American Journey” (1971), a chorus of voices speaking on the train bringing home Bobby Kennedy’s body, their subsequent and even more successful one, “Edie” (1982), was devoted to the Warholite-socialite Edie Sedgwick.

More here.

Graham Harman. Speculative Realism.

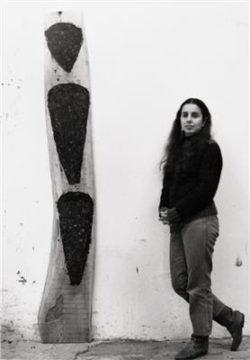

How Should Ana Mendieta’s Story Be Told?

Gabrielle Schwarz at Artforum:

HERE IS WHAT WE KNOW: In 1979, Ana Mendieta, a young, up-and-coming artist fresh off a solo show at the feminist co-op A.I.R. Gallery, met the older, more famous Carl Andre, a so-called founding father of Minimalism. The artists embarked on a romantic and, by several accounts, tempestuous relationship. In 1985, Mendieta died after falling from the window of Andre’s thirty-fourth-floor apartment in New York’s Greenwich Village. He was tried, and acquitted, for her murder. Now eighty-seven, Andre—still living, somewhat astoundingly, in that same apartment—has carried on with his career, exhibiting regularly in museums and galleries throughout the world. Yet not everyone is convinced of his innocence, as we hear in Death of an Artist, a six-episode podcast from writer-curator Helen Molesworth. In addition to offering a précis on the defects of the US justice system, the series reframes abiding questions about art through the lens of Mendieta’s case: Are artists’ lives—and deaths—relevant when discussing their work? What about when we suspect that they have committed a terrible crime? Who benefits from silence, and from speaking up?

HERE IS WHAT WE KNOW: In 1979, Ana Mendieta, a young, up-and-coming artist fresh off a solo show at the feminist co-op A.I.R. Gallery, met the older, more famous Carl Andre, a so-called founding father of Minimalism. The artists embarked on a romantic and, by several accounts, tempestuous relationship. In 1985, Mendieta died after falling from the window of Andre’s thirty-fourth-floor apartment in New York’s Greenwich Village. He was tried, and acquitted, for her murder. Now eighty-seven, Andre—still living, somewhat astoundingly, in that same apartment—has carried on with his career, exhibiting regularly in museums and galleries throughout the world. Yet not everyone is convinced of his innocence, as we hear in Death of an Artist, a six-episode podcast from writer-curator Helen Molesworth. In addition to offering a précis on the defects of the US justice system, the series reframes abiding questions about art through the lens of Mendieta’s case: Are artists’ lives—and deaths—relevant when discussing their work? What about when we suspect that they have committed a terrible crime? Who benefits from silence, and from speaking up?

more here.

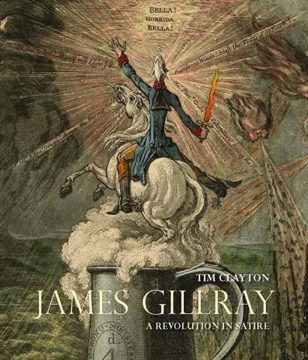

James Gillray: A Revolution in Satire

Freya Johnston at Literary Review:

Children do not tend to feature prominently in the satirical works of the ‘Prince of Caricatura’, James Gillray. As someone professionally committed to excoriating the politicians and celebrities of his day, he was paid to train his eye on the grown-ups. One exception to this rule comes in A March to the Bank, a vast, elaborate print of 1787. It was published in the wake of the anti-Catholic Gordon Riots in London and reflects the city’s outrage at the subsequent military crackdown on public disorder. Gillray blends straight portraiture with lurid exaggeration in his etching: an absurdly dandified, impossibly skinny officer goosesteps over a mob of Londoners, who lie crushed and abandoned in various states of disarray. At the centre of the picture, with the officer’s foot daintily poised on her midriff, lies the grotesque, ungainly figure of a fishwife, still grasping a basket of eels, her hefty legs splayed wide open. A fragment of cloth barely covers her genitals. Next to her lies a baby boy, perhaps her son, who is naked from the waist down and spread-eagled on the edge of the pavement. An impassive-looking soldier has placed the tip of his boot squarely on the child’s face.

Children do not tend to feature prominently in the satirical works of the ‘Prince of Caricatura’, James Gillray. As someone professionally committed to excoriating the politicians and celebrities of his day, he was paid to train his eye on the grown-ups. One exception to this rule comes in A March to the Bank, a vast, elaborate print of 1787. It was published in the wake of the anti-Catholic Gordon Riots in London and reflects the city’s outrage at the subsequent military crackdown on public disorder. Gillray blends straight portraiture with lurid exaggeration in his etching: an absurdly dandified, impossibly skinny officer goosesteps over a mob of Londoners, who lie crushed and abandoned in various states of disarray. At the centre of the picture, with the officer’s foot daintily poised on her midriff, lies the grotesque, ungainly figure of a fishwife, still grasping a basket of eels, her hefty legs splayed wide open. A fragment of cloth barely covers her genitals. Next to her lies a baby boy, perhaps her son, who is naked from the waist down and spread-eagled on the edge of the pavement. An impassive-looking soldier has placed the tip of his boot squarely on the child’s face.

more here.

Ant Milk: It Does a Colony Good

Joshua Sokol in The New York Times:

Orli Snir, a biologist at the Rockefeller University in New York, couldn’t keep her ants alive. She had plucked pupae from a colony of clonal raider ants, where the sesame seed-size offspring that looked like puffed rice cereal were being fussed over by both younger larvae and older adult ants. Then she had isolated each pupa into a tiny, dry test tube. And every time, they drowned. More specifically, each pupa was leaking so much watery, golden-tinted fluid it was struggling to breathe. But they lived when Dr. Snir whisked the fluid away with a capillary tube. Her humble observation led down a strange path of experiments toward a bizarre but inescapable conclusion: This mysterious ant goo functions a lot like milk.

Orli Snir, a biologist at the Rockefeller University in New York, couldn’t keep her ants alive. She had plucked pupae from a colony of clonal raider ants, where the sesame seed-size offspring that looked like puffed rice cereal were being fussed over by both younger larvae and older adult ants. Then she had isolated each pupa into a tiny, dry test tube. And every time, they drowned. More specifically, each pupa was leaking so much watery, golden-tinted fluid it was struggling to breathe. But they lived when Dr. Snir whisked the fluid away with a capillary tube. Her humble observation led down a strange path of experiments toward a bizarre but inescapable conclusion: This mysterious ant goo functions a lot like milk.

Not just one ant species uses this milk, either. Perhaps all ants do, according to a paper led by Dr. Snir that was published Wednesday in the journal Nature. It adds ants among other unexpected creatures like pigeons, spiders and beetles that feed each other milk-like fluids. And much like milk in mammals, it knits together ants of different generations — and the larger ant society, too. After first noticing the strange secretions, Dr. Snir scanned through the scientific literature and it seemed that her ant pupae were oozing something that was mostly unknown to science. She shared what she had found with her co-author, Daniel Kronauer, who leads a research group on ant evolution at Rockefeller. “My first thought was, ‘This is crazy,’” he said.

More here.

Lots of bad science still gets published. Here’s how we can change that

Sigal Samuel in Vox:

For over a decade, scientists have been grappling with the alarming realization that many published findings — in fields ranging from psychology to cancer biology — may actually be wrong. Or at least, we don’t know if they’re right, because they just don’t hold up when other scientists repeat the same experiments, a process known as replication. In a 2015 attempt to reproduce 100 psychology studies from high-ranking journals, only 39 of them replicated. And in 2018, one effort to repeat influential studies found that 14 out of 28 — just half — replicated. Another attempt found that only 13 out of 21 social science results picked from the journals Science and Nature could be reproduced.

For over a decade, scientists have been grappling with the alarming realization that many published findings — in fields ranging from psychology to cancer biology — may actually be wrong. Or at least, we don’t know if they’re right, because they just don’t hold up when other scientists repeat the same experiments, a process known as replication. In a 2015 attempt to reproduce 100 psychology studies from high-ranking journals, only 39 of them replicated. And in 2018, one effort to repeat influential studies found that 14 out of 28 — just half — replicated. Another attempt found that only 13 out of 21 social science results picked from the journals Science and Nature could be reproduced.

This is known as the “replication crisis,” and it’s devastating. The ability to repeat an experiment and get consistent results is the bedrock of science. If important experiments didn’t really find what they claimed to, that could lead to iffy treatments and a loss of trust in science more broadly. So scientists have done a lot of tinkering to try to fix this crisis. They’ve come up with “open science” practices that help somewhat — like preregistration, where a scientist announces how she’ll conduct her study before actually doing the study — and journals have gotten better about retracting bad papers. Yet top journals still publish shoddy papers, and other researchers still cite and build on them.

This is where the Transparent Replications project comes in.

More here.

Tuesday Poem

Brittany’s Tattoo

—The Haven House for homeless Women and Children

… Her tattoo is no stone-cold Lady Justice—

Tattered blindfold, sword, scales in balance—

… just the ink-black cursive word

Justice cutting over the upward

… thrust of her jugular—

from her throat to the jug band

… of her heart to the ovation

of her brain stretches that thin, blue tether.

………… Only Justice

…… because when Brittany needs to believe

the word’s wine-red truth, she presses

… that wormy vein to feel blood

thunder beneath her fingers.

by Lauren Marie Schmidt

from Filthy Labors

Curbstone Books 2017

The Greatest Films of All Time

From the website of the BFI:

In 1952, the Sight and Sound team had the novel idea of asking critics to name the greatest films of all time. The tradition became decennial, increasing in size and prestige as the decades passed.

In 1952, the Sight and Sound team had the novel idea of asking critics to name the greatest films of all time. The tradition became decennial, increasing in size and prestige as the decades passed.

The Sight and Sound poll is now a major bellwether of critical opinion on cinema and this year’s edition (its eighth) is the largest ever, with 1,639 participating critics, programmers, curators, archivists and academics each submitting their top ten ballot. What has risen up the ranks? What has fallen? Has 2012’s winner Vertigo held on to its title? Find out below.

More here.

Where Mauna Loa’s lava is coming from – and why Hawaii’s volcanoes are different from most

Gabi Laske in The Conversation:

The magma that comes out of Mauna Loa comes from a series of magma chambers found between about 1 and 25 miles (2 and 40 km) below the surface. These magma chambers are only temporary storage places with magma and gases, and are not where the magma originally came from.

The magma that comes out of Mauna Loa comes from a series of magma chambers found between about 1 and 25 miles (2 and 40 km) below the surface. These magma chambers are only temporary storage places with magma and gases, and are not where the magma originally came from.

The origin is much deeper in Earth’s mantle, perhaps more than 620 miles (1,000 km) deep. Some scientists even postulate that the magma comes from a depth of 1,800 miles (2,900 km), where the mantle meets Earth’s core.

Earth’s crust is made up of tectonic plates that are slowly moving, at about the same speed as a fingernail grows. Volcanoes typically occur where these plates either move away from each other or where one pushes beneath another. But volcanoes can also be in the middle of plates, as Hawaii’s volcanoes are in the Pacific Plate.

More here.

Glenn Gould: “How Mozart Became a Bad Composer”

Chokepoint Capitalism review – art for sale

Kitty Drake in The Guardian:

In this provocative book, Rebecca Giblin and Cory Doctorow argue that, today, every working artist is a bond servant. Culture is the bait adverts are sold around, but artists see almost nothing of the billions Google, Facebook and Apple and make off their backs. We have entered a new era of “chokepoint capitalism”, in which businesses snake their way between audiences and creatives to harvest money that should rightfully belong to the artist.

In this provocative book, Rebecca Giblin and Cory Doctorow argue that, today, every working artist is a bond servant. Culture is the bait adverts are sold around, but artists see almost nothing of the billions Google, Facebook and Apple and make off their backs. We have entered a new era of “chokepoint capitalism”, in which businesses snake their way between audiences and creatives to harvest money that should rightfully belong to the artist.

An early chapter sketches the growth of Amazon, a relatively straightforward example of the phenomenon. First the company got publishers hooked on its site by offering them great rates. Once it became apparent they couldn’t survive without it, Amazon reduced their cut of the cover price. The image of the chokepoint that recurs throughout this book is an evocatively gruesome one. There is just one pipeline through which authors can access their readers, and Amazon is squeezing it, dictating exactly which books make it to the other side, and at what price.

More here.

The Gendered Ape, Essay 10: No Gender-Neutral Upbringing For Apes

Editor’s Note: Frans de Waal’s new book, Different: Gender Through the Eyes of a Primatologist, has generated some controversy and misunderstanding. He will address these issues in a series of short essays which will be published at 3QD and can all be seen in one place here. More comments on these essays can also be seen at Frans de Waal’s Facebook page.

by Frans de Waal

No one can deny the traditional (and ongoing) gender inequality in human society, which disadvantages girls and women. It’s a huge injustice that we need to fight.

But who says that elimination of gender differences is the solution? Or that we need to promote gender-neutrality?

Of the two words in “gender inequality,” only one is a problem, and it isn’t “gender.”

A fully gender-neutral upbringing of children may not even be feasible. Human biology isn’t blind to sex. The breastmilk of mothers, for example, varies dependent on whether she’s nursing a boy or a girl. Milk for male babies has a greater energy content. Milk of monkey mothers shows the same difference.

Young male primates are more energetic and rambunctious than same-aged females. When hundreds of children in different nations were outfitted with accelerometers to measure body movements, boys showed far more bursts of vigorous locomotion than girls. That boys are also three times more likely than girls to be diagnosed with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) reflects the same difference. Read more »

Tales From The Crypt(o)

by Rafaël Newman

Because I work part time developing a terminology database at a large econometric institute; and because it is important that, in this capacity, I remain abreast not only of raw vocabulary but also of the substance of recent developments in financial technology, known by its Orwellian moniker “FinTech”; and because the owl of Minerva flies at dusk—for all these reasons I recently dusted off my book-bag, packed my reading glasses and a roll of antacid, and registered for a course on blockchain, crypto, and digital currencies.

The three-month program I attended, leading to a so-called Certificate of Advanced Studies (CAS), was offered at the University of Zurich’s Blockchain Center, an interdisciplinary institute ranked fourth for university teaching of distributed ledger technology worldwide. And indeed, my fellow students had come from as far afield as Australia, India, and Brazil, as well as from various corners of Switzerland and Europe, presumably in the hopes of profiting from cutting-edge technical expertise in their work back home as computer programmers, bankers, and jurists.

Instruction was provided by a changing roster of professors in three modules of several full days each, devoted respectively to the IT, economic, and legal dimensions of the new(ish) technology. Each module was punctuated by an assignment, to permit evaluation of the participants: the IT module closed with an online multiple-choice test; the economic component was rounded out with a series of group-work exercises; and the legal section, and thus the course as a whole, concluded with a written essay, on a topic chosen from among suggestions made by the various professors, one of whom, depending on the student’s choice of topic, would then serve as supervisor. Read more »

Monday Poem

“Shu” is the single teaching of Confucius and “jen”

it’s counterpart. Shu means reciprocity; jen is love,

kindness and goodness. T’ien is heaven.

–Confucius and the Teaching of Goodness

Shu and Jen

Goodness came as two hearts and sat beside me.

“My name is Shu,” they said. At that moment

two birds flew through an open window generously wide

and, pointing, Shu said, “Jen.”

The two hearts of Shu, in duet, said,

“What can we do for you?”

The two birds of Jen sang,

“Looks like you need a friend.”

“The world is split in two, and so are you,” said Shu

“See the birds of Jen, she said? They feed each other and

so are free in T’ien.”

“Think of me,” said Shu

and you may be free too.”

Jim Culleny, 6/18/11

A Paradox Concerning Scientists and History

by David Kordahl

I’ve been thinking again about the relationship of scientists to the history of science. Lorraine Daston, the historian and philosopher of science, was recently interviewed for Marginalia, where her interviewer asked a strongly worded question. “Scientists are—I don’t want to put it too provocatively—but frankly they’re afraid of the history of their own discipline. What do you think that means?”

Daston was not quite willing to put all the blame at the feet of scientists. Historians of science, she remarked, have become more specialized, making their work less useful to scientists. Likewise, philosophers have failed to “remake of the concept of truth that does justice to the historical dynamism of science.” But then there’s the scientists themselves, who “consider almost anything which is not within their discipline, including other sciences, to be blather. So, there’s quite enough blame to go around in terms of explaining […] this impasse of mutual incomprehension.”

When this interview was released, it prompted some online chatter. Some scientists reading the interview did not see themselves in Daston’s characterization, since scientists do not, in general, consider themselves uninterested in the history of science—quite the opposite. The problem, for such history-interested scientists, was of approach rather than content.

To explore the basic distinction between “science history for scientists” and “science history for historians-and-philosophers-of-science,” I’ll use two complimentary books. Einstein’s Fridge: How the Difference Between Hot and Cold Explains the Universe, out last year from the science writer Paul Sen, exemplifies the former approach, where history provides a narrative scaffold to lead us gently toward our modern scientific theories. Inventing Temperature: Measurement and Scientific Progress, the 2004 work by the historian and philosopher of science Hasok Chang, is a classic example of the latter, where history is used as a proving ground to show that science and its history is more complicated than most scientists care to admit. Read more »

Japanese and the Empty Mind

by Leanne Ogasawara

1.

Ten years have passed since I left Japan. And it has been about five years since I stepped away from professional translation. I have made little effort to retain my Japanese, and so it has hardly been surprising to find my language skills falling away. There have been times where I even took a willful enjoyment realizing just how fast all those years of hard work could fade away. Like a colorful mandala made of sand that Tibetan monks labored to create and then destroy, my ability to write in Japanese disappeared overnight.

The more passive pursuits of reading and listening have proven to be less slippery. But I no longer have that feeling of being a different person in thinking and dreaming in Japanese. It’s gone. And my son, who learned Japanese as his native language, lost his skills even faster than I did. People sometimes say to me that a person can’t lose their native language, but it’s simply not true. I have met people who lost their first tongues time and time again. My son, who left Japan at seven years old, might have Japanese in their somewhere, but it is buried deep.

Effortless to learn, it’s also easy to lose languages in childhood.

In contrast, to learn a second language as an adult is a Herculean undertaking. Neither quick nor easy, it took me a decade of serious study to feel confident in Japanese.

Last week, Claire Chambers wrote a marvelous essay in these pages called Beginning Hindi with a Beginner’s Mind. By sheer coincidence, her essay mentioned a memoir that I am currently reading called Dreaming in Hindi. Written by Katherine Russell Rich, it is about the author’s year of language study in the romantic desert city of Udaipur. Read more »

Perceptions

Ceci n’est pas un miroir

by Akim Reinhardt

It’s not so much that I’m like my father. Rather, I sometimes feel as I understood him to be.

It’s not so much that I’m like my father. Rather, I sometimes feel as I understood him to be.

My mother? Not so much.

Part of it might have to do with sex. My father was a man. I’m a man. But I can’t really feel like a woman. I can feel for a woman. I can empathize. And I can listen when a woman describes her life to me. But I can never fully experience it for myself beyond the vicarious. It’s like being black or gay or someone who doesn’t speak a word of English. There’s a gap I can’t fully cross, a way of being I can’t have short of a plot twist in one of those Freaky Friday body swap comedies .

Is that why the inevitably male patriarchal priests and prophets fashioned a one, true male God? Because aside from the idea that only men should rule, and a hundred other sexist reasons, they could not imagine the soul of a woman?

But that only helps explain why I never feel as I understand my mother to be. Why do I sometimes feel as I understood my father to be?

I’m half of each of them. And if someone asks, I often describe myself as half-Jewish and half-redneck. It’s an incredibly facile and reductionist response. But it’s also an answer the questioner isn’t expecting, and probably isn’t even familiar with. So while seeming to offer little beyond stereotype, it also mildly confuses the questioner without intimidating them. That in turn gets them thinking. It can be good to put someone on their back foot when they ask you that question.

You know the question.

Peeling back that pat answer a bit forces me to remember who he was and wasn’t. A redneck? It was hardly some badge he wore, though he didn’t shy away from the label if it were hung on him. But one had to be careful in ways that New Yorkers might not know how to. I remember him angrily explaining to me once, after I’d made an offhanded comment, that there was a world of a difference between a redneck and white trash. And that he was never the latter. Read more »