Fixing Cars

I like the argument that man is alone in the universe,

and ipso facto its most intelligent being.

It proves there is no God, or if there is,

it’s the god of low SAT scores.

Astronomers debate the dark matter between stars.

I picture a conversational pause with a Trump apologist,

each party wondering, What planet?

If I read the moon right tonight, there is no reading it.

If I tell my kid sister the stars are eyes twinkling,

why do their cold winks give me the shivers?

The smartest kid on our block couldn’t jump-start

his engine if he was stuck on the wrong end of town

and his life depended on it. I can’t read my tax form.

I fix his cars, he interprets the IRS,

and under earth’s starry hood,

we solve the problems of the universe.

by Kent Newkirk

from Rattle, Winter, 2009

—For the sake of currency, one word in this poem has been swapped for another but

it has not altered in any way the poem’s thrust or relevance. The more things change

the more they remain the same, they say.

It’s all very meticulous, even his horror, which is considerable when it comes to the way the bishops covered up for their paedophile priests. On every subject, Tóibín’s writing is what people these days inevitably describe as nuanced, a word that has become a kind of shorthand for expressing a person’s rare ability to understand – or to try to understand – the foibles of others (how sad that this should be thought unusual). But he can be gripping, too. This country that censored the hell out of people’s hearts is so much his territory. If the speed with which the power of the church in Ireland has been undermined is still astonishing, it’s nevertheless important to consider the hold it may continue to have over those citizens – Tóibín is one – who remember when its authority was ironclad. In the end, this is a book of shadows: tumours in testicles, fog in Venice, expensively clad cardinals who may be up to no good.

It’s all very meticulous, even his horror, which is considerable when it comes to the way the bishops covered up for their paedophile priests. On every subject, Tóibín’s writing is what people these days inevitably describe as nuanced, a word that has become a kind of shorthand for expressing a person’s rare ability to understand – or to try to understand – the foibles of others (how sad that this should be thought unusual). But he can be gripping, too. This country that censored the hell out of people’s hearts is so much his territory. If the speed with which the power of the church in Ireland has been undermined is still astonishing, it’s nevertheless important to consider the hold it may continue to have over those citizens – Tóibín is one – who remember when its authority was ironclad. In the end, this is a book of shadows: tumours in testicles, fog in Venice, expensively clad cardinals who may be up to no good. Remember boredom? The first English translation of the French writer

Remember boredom? The first English translation of the French writer  S

S It was late in 1972 — a year in which the science of genetic engineering really began to sizzle — that two California researchers announced the unusually tidy transfer of genetic information from one bacterium to another with help from a specialized enzyme. It was a scientifically heralded result, but behind the hoopla was just one small catch. The information transferred enabled a common human disease bacterium, E. coli, to resist not just one antibiotic, but two. “Alarm bells should have rung,” writes Matthew Cobb, in his deeply researched and often deeply troubling history of gene science. And that nothing did ring — that scientific success trumped the obvious risks of the work — becomes the focus of his book’s primary inquiry: whether a research community capable of altering life is also capable of putting ethical decisions first.

It was late in 1972 — a year in which the science of genetic engineering really began to sizzle — that two California researchers announced the unusually tidy transfer of genetic information from one bacterium to another with help from a specialized enzyme. It was a scientifically heralded result, but behind the hoopla was just one small catch. The information transferred enabled a common human disease bacterium, E. coli, to resist not just one antibiotic, but two. “Alarm bells should have rung,” writes Matthew Cobb, in his deeply researched and often deeply troubling history of gene science. And that nothing did ring — that scientific success trumped the obvious risks of the work — becomes the focus of his book’s primary inquiry: whether a research community capable of altering life is also capable of putting ethical decisions first. Missing persons cases are seldom about finding someone. Too often, people who have disappeared are not missing at all. They are either hiding or long dead, possibly victims of murders waiting to be solved. Such cases, in short, are best to avoid. But when I heard that there had been recent sightings of the long-lost Wandering Jew, I knew I had to investigate.

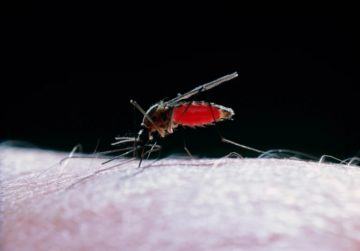

Missing persons cases are seldom about finding someone. Too often, people who have disappeared are not missing at all. They are either hiding or long dead, possibly victims of murders waiting to be solved. Such cases, in short, are best to avoid. But when I heard that there had been recent sightings of the long-lost Wandering Jew, I knew I had to investigate. Blood-sucking mosquitoes have their uses. An innovative approach analysing their last blood meals can reveal evidence of infection in the people or animals that the flying insects feasted on.

Blood-sucking mosquitoes have their uses. An innovative approach analysing their last blood meals can reveal evidence of infection in the people or animals that the flying insects feasted on. Can Americans’ trust in elections be rebuilt?

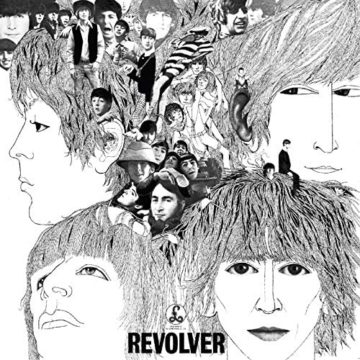

Can Americans’ trust in elections be rebuilt? Weber says that most writings about the Beatles can be categorised into one of four principal narratives ‑ four ways of seeing and telling the band’s story. The first and earliest of these is the Fab Four Narrative. This is the more or less official version of the Beatles that evolved following their initial breakthrough. It was propagated by a largely friendly media nudged along by the Beatles themselves, their management and publicists. In the Fab Four Narrative, the Beatles are depicted as four friends whose relationship with each other is easy and free of tension. This is how they come across in their early interviews, their monthly fan magazine, and, especially, in their first two films: A Hard Day’s Night and Help. In Help, for example, the fictionalised Beatles live in a luxurious communal home that is, by mid-sixties standards, high-tech. These are rich young men, leisured and with few responsibilities, but who get along together, well enough to live in the same shared space like perpetual teenagers. As Weber comments, these mainstream films were especially important in differentiating one Beatle from another for a wider public (Jonathan Miller, commenting when they were new on the scene, had thought they all looked the same, like the Midwich Cuckoos).

Weber says that most writings about the Beatles can be categorised into one of four principal narratives ‑ four ways of seeing and telling the band’s story. The first and earliest of these is the Fab Four Narrative. This is the more or less official version of the Beatles that evolved following their initial breakthrough. It was propagated by a largely friendly media nudged along by the Beatles themselves, their management and publicists. In the Fab Four Narrative, the Beatles are depicted as four friends whose relationship with each other is easy and free of tension. This is how they come across in their early interviews, their monthly fan magazine, and, especially, in their first two films: A Hard Day’s Night and Help. In Help, for example, the fictionalised Beatles live in a luxurious communal home that is, by mid-sixties standards, high-tech. These are rich young men, leisured and with few responsibilities, but who get along together, well enough to live in the same shared space like perpetual teenagers. As Weber comments, these mainstream films were especially important in differentiating one Beatle from another for a wider public (Jonathan Miller, commenting when they were new on the scene, had thought they all looked the same, like the Midwich Cuckoos). THE WORD “GENIAL” IN ENGLISH

THE WORD “GENIAL” IN ENGLISH I first read the Book of Revelation in a green pocket-size King James New Testament published by the motel missionaries Gideons International. I was in seventh grade. I remember reading the tiny Bible in the hallway outside my chemistry classroom, in which lurked a boy I loathed named Glenn, who would make fun of my Journey T-shirts. It would be years before I really got into Iron Maiden, but at my friend Jonathan’s house I’d heard Barry Clayton’s creepy recitation of Revelation 13:18 on the title track of The Number of the Beast: “Let him who hath understanding reckon the number of the beast: for it is a human number; its number is six hundred and sixty-six.”

I first read the Book of Revelation in a green pocket-size King James New Testament published by the motel missionaries Gideons International. I was in seventh grade. I remember reading the tiny Bible in the hallway outside my chemistry classroom, in which lurked a boy I loathed named Glenn, who would make fun of my Journey T-shirts. It would be years before I really got into Iron Maiden, but at my friend Jonathan’s house I’d heard Barry Clayton’s creepy recitation of Revelation 13:18 on the title track of The Number of the Beast: “Let him who hath understanding reckon the number of the beast: for it is a human number; its number is six hundred and sixty-six.” Over the years, Marsha Farmer had learned what to look for. As she drove the back roads of rural Alabama, she kept an eye out for dilapidated homes and trailers with wheelchair ramps. Some days, she’d ride the one-car ferry across the river to Lower Peach Tree and other secluded hamlets where a few houses lacked running water and bare soil was visible beneath the floorboards. Other times, she’d scan church prayer lists for the names of families with ailing members.

Over the years, Marsha Farmer had learned what to look for. As she drove the back roads of rural Alabama, she kept an eye out for dilapidated homes and trailers with wheelchair ramps. Some days, she’d ride the one-car ferry across the river to Lower Peach Tree and other secluded hamlets where a few houses lacked running water and bare soil was visible beneath the floorboards. Other times, she’d scan church prayer lists for the names of families with ailing members. After the Internet arrived and flooded the market with new voices, some outlets found that instead of going after the whole audience, it made more financial sense to pick one demographic and dominate it. How? That’s easy. You feed the audience news you know they will like. When Fox had success targeting suburban and rural, mostly white, mostly older conservatives – the late Fox News chief Roger Ailes infamously described his audience as “55 to dead” – other companies soon followed suit.

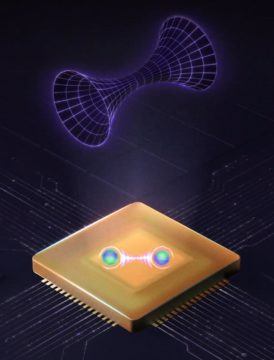

After the Internet arrived and flooded the market with new voices, some outlets found that instead of going after the whole audience, it made more financial sense to pick one demographic and dominate it. How? That’s easy. You feed the audience news you know they will like. When Fox had success targeting suburban and rural, mostly white, mostly older conservatives – the late Fox News chief Roger Ailes infamously described his audience as “55 to dead” – other companies soon followed suit. Physicists have purportedly created the first-ever wormhole, a kind of tunnel theorized in 1935 by Albert Einstein and Nathan Rosen that leads from one place to another by passing into an extra dimension of space.

Physicists have purportedly created the first-ever wormhole, a kind of tunnel theorized in 1935 by Albert Einstein and Nathan Rosen that leads from one place to another by passing into an extra dimension of space. With or without the COVID-19 pandemic, China has maintained a greater capacity to control the internal movement of its population than perhaps any other country in the world. This is primarily enforced through the household registration system (hukou) which has linked the provision of social services to regional locales since 1958. Under Deng Xiaoping, China set about constructing a national labor market, which today allows citizens to enjoy the narrow market freedom to seek employment throughout the country. But social citizenship, including access to state subsidized health care, education, pensions, and housing, is structured at the level of the city.

With or without the COVID-19 pandemic, China has maintained a greater capacity to control the internal movement of its population than perhaps any other country in the world. This is primarily enforced through the household registration system (hukou) which has linked the provision of social services to regional locales since 1958. Under Deng Xiaoping, China set about constructing a national labor market, which today allows citizens to enjoy the narrow market freedom to seek employment throughout the country. But social citizenship, including access to state subsidized health care, education, pensions, and housing, is structured at the level of the city.