by Marie Snyder

The anger that escalated at a recent Ottawa-Carlton school board meeting when a trustee proposed and lost a motion to mandate masks, in a setting that typically elicits polite discussion, makes it seem like this type of anger is new and shocking in its inappropriateness. But this video of the history of masks, and memories of what many of us lived through when we imposed smoking bans and seatbelts years ago, makes it clear that people have always been fired up by any new restriction. Masks may be even more enraging because they’ve also become symbolic of a danger and harm we’d like to forget.

The anger that escalated at a recent Ottawa-Carlton school board meeting when a trustee proposed and lost a motion to mandate masks, in a setting that typically elicits polite discussion, makes it seem like this type of anger is new and shocking in its inappropriateness. But this video of the history of masks, and memories of what many of us lived through when we imposed smoking bans and seatbelts years ago, makes it clear that people have always been fired up by any new restriction. Masks may be even more enraging because they’ve also become symbolic of a danger and harm we’d like to forget.

But more than that, this type of anger that targeted the specific trustee with emails and phone calls, that included vile sexist and racist comments and threats, is more reminiscent of GamerGate, when a few women dared to criticize some games and were brutally harassed online and doxed, provoking at least one to move. This Vox article explains what needs to be done to prevent these occurrences:

It’s crucial to understand how, when, and why an online mob is expressing outrage before you decide how to respond to it. Gamergate should have taught businesses that online mobs can and do look for excuses to be outraged, as a pretext to harass and abuse their targets. There’s a difference between organic outrage that arises because an employee actually does something outrageous, and invented outrage that’s an excuse to harass someone. . . . 2014 should have been the year the cultural conversation began to acknowledge how serious aggression toward women really is. It wasn’t.

This understanding of the situation suggests that an outlet for anger is the point and that gaming was just a catalyst or merely the easiest avenue for the anger to seem remotely reasonable. It’s like when a hungry or tired toddler is upset with a random toy until that inner irritation is resolved. The grade school version finds a scapegoat to unload on and then they discover the glee of having power over another. We need to resolve these inner irritations and the joy of domination before people become adults with a greater capacity to cause lasting harm. Read more »

The word arrived from the furniture store. They have come! After five months of supply-chain suspended animation, our 15 feet of 72-inch-high bookcases are here. Bibliophiles everywhere (well, everywhere in my family) raised their voices in praise.

The word arrived from the furniture store. They have come! After five months of supply-chain suspended animation, our 15 feet of 72-inch-high bookcases are here. Bibliophiles everywhere (well, everywhere in my family) raised their voices in praise.

most gut-wrenching exploration of what it feels like to be cancelled is in a novel written long before that term had become a weapon in the culture wars. In Philip Roth’s The Human Stain, published in 2000, Coleman Silk, a professor and former dean at the fictional Athena College, is teaching a seminar with 14 students.

most gut-wrenching exploration of what it feels like to be cancelled is in a novel written long before that term had become a weapon in the culture wars. In Philip Roth’s The Human Stain, published in 2000, Coleman Silk, a professor and former dean at the fictional Athena College, is teaching a seminar with 14 students. A year ago Bitcoin and other cryptocurrencies were selling at record prices, with a combined market value of around

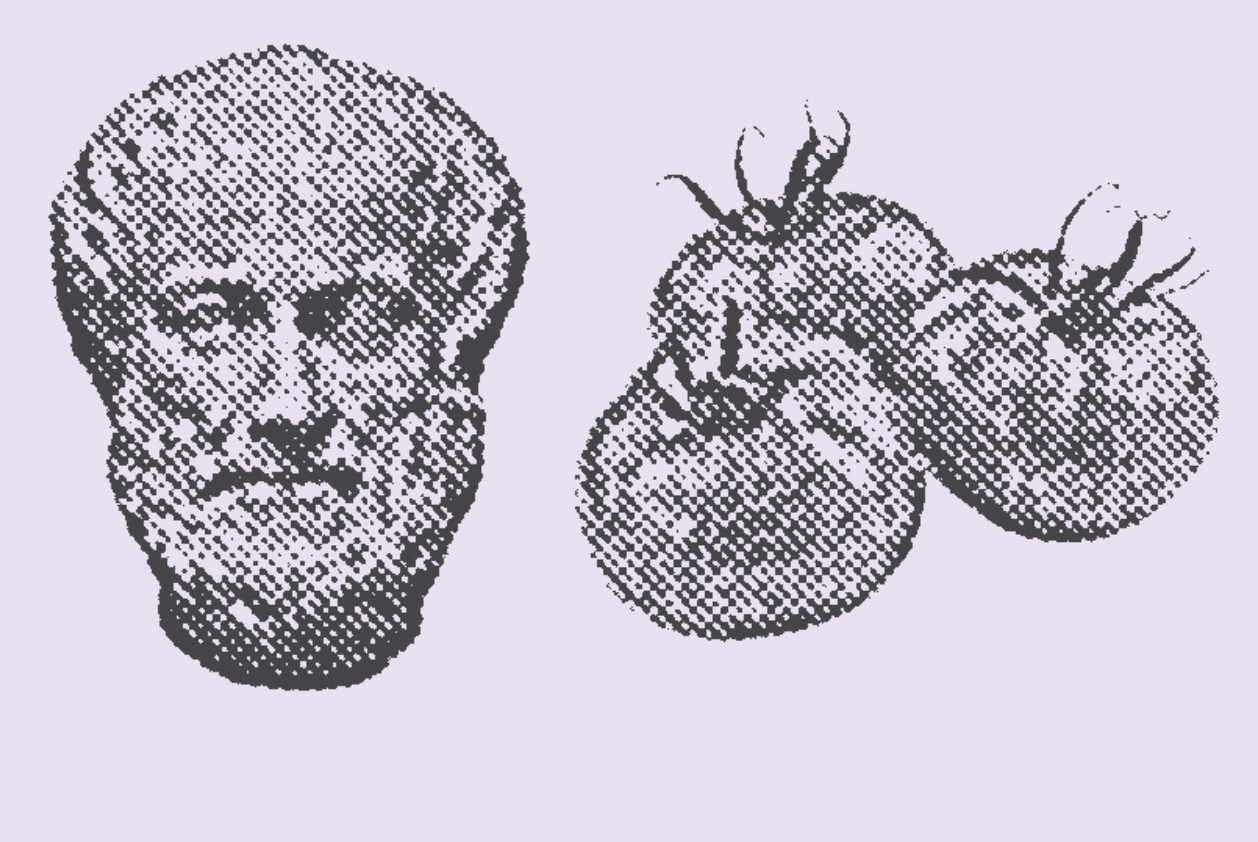

A year ago Bitcoin and other cryptocurrencies were selling at record prices, with a combined market value of around  When Aristotle sniffed an apple, he smelled it. When he bit into the apple and the flesh touched his tongue, he tasted it. But he overlooked something that caused 2,000 years of confusion.

When Aristotle sniffed an apple, he smelled it. When he bit into the apple and the flesh touched his tongue, he tasted it. But he overlooked something that caused 2,000 years of confusion. The Saudi prince was detained all night. As daylight broke, he staggered out of the king’s palace in Mecca. His personal bodyguards, who tailed him everywhere, were missing. The prince was led to a waiting car. He was free to leave – but he would soon discover that freedom was not very different from detention.

The Saudi prince was detained all night. As daylight broke, he staggered out of the king’s palace in Mecca. His personal bodyguards, who tailed him everywhere, were missing. The prince was led to a waiting car. He was free to leave – but he would soon discover that freedom was not very different from detention. “I am sick to death of cleverness,” wrote the very clever Oscar Wilde in The Importance of Being Earnest. “Everybody is so clever nowadays…. The thing has become an absolute public nuisance.” The philosopher Ludwig Wittgenstein was tormented by the thought that he was “merely clever” and criticized himself and others for valuing cleverness over genuine wisdom. Søren Kierkegaard, who placed a genuinely religious life before a merely aesthetic one, wrote that “the law for the religious is to act in opposition to cleverness.”

“I am sick to death of cleverness,” wrote the very clever Oscar Wilde in The Importance of Being Earnest. “Everybody is so clever nowadays…. The thing has become an absolute public nuisance.” The philosopher Ludwig Wittgenstein was tormented by the thought that he was “merely clever” and criticized himself and others for valuing cleverness over genuine wisdom. Søren Kierkegaard, who placed a genuinely religious life before a merely aesthetic one, wrote that “the law for the religious is to act in opposition to cleverness.” Janet Afary and Kevin B. Anderson in Dissent:

Janet Afary and Kevin B. Anderson in Dissent: Bruno Latour in Green:

Bruno Latour in Green: Kate Mackenzie, Lee Harris, and Tim Sahay in The Polycrisis at Phenomenal World:

Kate Mackenzie, Lee Harris, and Tim Sahay in The Polycrisis at Phenomenal World: