The Long Boat

When his boat snapped loose

from its mooring, under

the screaking of the gulls,

he tried at first to wave

to his dear ones on shore,

but in the rolling fog

they had already lost their faces.

Too tired even to choose

between jumping and calling,

somehow he felt absolved and free

of his burdens, those mottoes

stamped on his name-tag:

conscience, ambition, and all

that caring.

He was content to lie down

with the family ghosts

in the slop of his cradle,

buffeted by the storm,

endlessly drifting.

Peace! Peace!

To be rocked by the Infinite!

As if it didn’t matter

which way was home;

as if he didn’t know

he loved the earth so much

he wanted to stay forever.

by Stanley Kunitz

from The Collected Poems

The oldest DNA ever recovered has revealed a remarkable two-million-year-old ecosystem in Greenland, including the presence of an unlikely explorer: the mastodon.

The oldest DNA ever recovered has revealed a remarkable two-million-year-old ecosystem in Greenland, including the presence of an unlikely explorer: the mastodon. Why is april

Why is april

The medieval bubonic plague pandemic was a major historical event. But what happened next? To give myself some grounding on this topic, I previously reviewed

The medieval bubonic plague pandemic was a major historical event. But what happened next? To give myself some grounding on this topic, I previously reviewed  The Congressional decision to

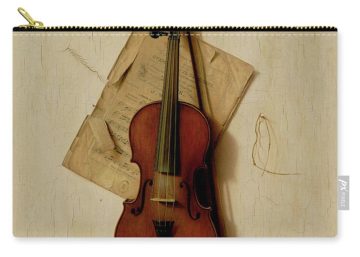

The Congressional decision to  As in magic, viewers of trompe l’oeil know they’re being deceived, and are in on the joke. And there may be something hard-wired in our attraction to those tricks. Gustav Kuhn, Reader in Psychology at Goldsmith’s, University of London, studies cognition and illusions, specifically in magic. No one really knows why we like to be tricked, he says, but he speculates that the attraction comes from “some sort of deep-rooted cognitive mechanism that encourages us to explore the unknown.” Studies of infants point in that direction. “Cognitive conflict is at the essence of magic,” he says. If you hide an object, then reveal the empty space where it was, “For really young infants, they don’t have a concept of object permanency, and so it doesn’t violate their assumptions about the world and they’re not really that interested. However, after the age of about two, where this violates their assumptions, they become captivated.”

As in magic, viewers of trompe l’oeil know they’re being deceived, and are in on the joke. And there may be something hard-wired in our attraction to those tricks. Gustav Kuhn, Reader in Psychology at Goldsmith’s, University of London, studies cognition and illusions, specifically in magic. No one really knows why we like to be tricked, he says, but he speculates that the attraction comes from “some sort of deep-rooted cognitive mechanism that encourages us to explore the unknown.” Studies of infants point in that direction. “Cognitive conflict is at the essence of magic,” he says. If you hide an object, then reveal the empty space where it was, “For really young infants, they don’t have a concept of object permanency, and so it doesn’t violate their assumptions about the world and they’re not really that interested. However, after the age of about two, where this violates their assumptions, they become captivated.” The end of history was not an idea that was original to Fukuyama; rather, as befits an age of ideological exhaustion, it was a vintage reissue harking back to an earlier era. The idea was hatched in the rubble of the Second World War and set the tone of intellectual life in the 1950s. Jacques Derrida once reminisced that it was the “daily bread” on which aspiring philosophers were raised back then. Its charismatic impresario was the Russian-born French philosopher Alexandre Kojève. Many others, however, came to terms with the idea the way one does with an ominous prognosis. For the German philosopher Karl Löwith, the end of history was primarily a crisis of meaning and purpose regarding the direction of human existence; for Talmudic scholar and charismatic intellectual Jacob Taubes, it was the exhaustion of eschatological hopes, the last of which were vested in Marxism; for the French philosopher Emmanuel Mounier, the collapse of secular and religious faith; for the theologian Rudolf Bultmann, it meant that the task of finding meaning in human existence had become a purely individual burden; and for the political theorist Judith Shklar, it morphed into an “eschatological consciousness” that “extended from the merely cultural level” to the point where “all mankind is faced with its final hour.”

The end of history was not an idea that was original to Fukuyama; rather, as befits an age of ideological exhaustion, it was a vintage reissue harking back to an earlier era. The idea was hatched in the rubble of the Second World War and set the tone of intellectual life in the 1950s. Jacques Derrida once reminisced that it was the “daily bread” on which aspiring philosophers were raised back then. Its charismatic impresario was the Russian-born French philosopher Alexandre Kojève. Many others, however, came to terms with the idea the way one does with an ominous prognosis. For the German philosopher Karl Löwith, the end of history was primarily a crisis of meaning and purpose regarding the direction of human existence; for Talmudic scholar and charismatic intellectual Jacob Taubes, it was the exhaustion of eschatological hopes, the last of which were vested in Marxism; for the French philosopher Emmanuel Mounier, the collapse of secular and religious faith; for the theologian Rudolf Bultmann, it meant that the task of finding meaning in human existence had become a purely individual burden; and for the political theorist Judith Shklar, it morphed into an “eschatological consciousness” that “extended from the merely cultural level” to the point where “all mankind is faced with its final hour.” What do you give the queen who has everything? When Mark Antony was wondering how to impress Cleopatra in the run-up to the battle of Actium in 31BC, he knew that jewellery would hardly cut it. The queen of the Ptolemaic kingdom of Egypt had recently dissolved a giant pearl in vinegar and then proceeded to drink it, just because she could. In the face of such exhausted materialism, the Roman general knew that he would have to pull out the stops if he was to win over the woman with whom he was madly in love. So he arrived bearing 200,000 scrolls for the great library at Alexandria. On a logistical level this worked well: since the library was the biggest storehouse of books in the world, Cleopatra almost certainly had the shelf space. As a romantic gesture, it was equally provocative. Within weeks the middle-aged lovers were embarked on the final chapter of their erotic misadventure, the one which would mark the beginning of the end both for them and for Alexandria’s fabled library.

What do you give the queen who has everything? When Mark Antony was wondering how to impress Cleopatra in the run-up to the battle of Actium in 31BC, he knew that jewellery would hardly cut it. The queen of the Ptolemaic kingdom of Egypt had recently dissolved a giant pearl in vinegar and then proceeded to drink it, just because she could. In the face of such exhausted materialism, the Roman general knew that he would have to pull out the stops if he was to win over the woman with whom he was madly in love. So he arrived bearing 200,000 scrolls for the great library at Alexandria. On a logistical level this worked well: since the library was the biggest storehouse of books in the world, Cleopatra almost certainly had the shelf space. As a romantic gesture, it was equally provocative. Within weeks the middle-aged lovers were embarked on the final chapter of their erotic misadventure, the one which would mark the beginning of the end both for them and for Alexandria’s fabled library. A vacation in the Catskills, one of those beautiful summer days which seem to go on forever, with family friends down at a local pond. I must have been six. I waded around happily, in and out of the tall grasses that grew in the murky water, but when I emerged onto the shore my legs were studded with small black creatures. “Leeches! Don’t touch them!” my mother yelled. I stood terrified. My parents’ friends lit cigarettes and applied the glowing ends to the parasites, which exploded, showering me with blood.

A vacation in the Catskills, one of those beautiful summer days which seem to go on forever, with family friends down at a local pond. I must have been six. I waded around happily, in and out of the tall grasses that grew in the murky water, but when I emerged onto the shore my legs were studded with small black creatures. “Leeches! Don’t touch them!” my mother yelled. I stood terrified. My parents’ friends lit cigarettes and applied the glowing ends to the parasites, which exploded, showering me with blood. Technological advances such as Elon Musk’s Neuralink device are meant to be implanted in people’s skulls to interface their brain with powerful computers via the internet. Neuralink’s device will be designed to bring information to subjects’ minds and, possibly, to help subjects acquire skills. If the device works as intended, we will be able to acquire information via a device that is not a natural part of us. Will the acquisition of this information give us knowledge? Will we really know how to do whatever it is that Neuralink’s device assists us in doing? How we answer these questions is important. Knowledge is, arguably, an important human achievement, and if Neuralink’s device (or some other technological assistance) makes it so that we acquire information without knowing, or if it makes it so we do not know how to do what we do as a result of the technological assistance, then we have thereby reduced our ability to succeed in ways important to our humanity. Further, knowledge is arguably required for moral action. Performing a charitable act in full knowledge (and knowing how to perform the act) is more praiseworthy than performing the act in ignorance. If, however, our reliance on new technology diminishes our ability to act knowledgably, then we are less praiseworthy for having relied on that technology.

Technological advances such as Elon Musk’s Neuralink device are meant to be implanted in people’s skulls to interface their brain with powerful computers via the internet. Neuralink’s device will be designed to bring information to subjects’ minds and, possibly, to help subjects acquire skills. If the device works as intended, we will be able to acquire information via a device that is not a natural part of us. Will the acquisition of this information give us knowledge? Will we really know how to do whatever it is that Neuralink’s device assists us in doing? How we answer these questions is important. Knowledge is, arguably, an important human achievement, and if Neuralink’s device (or some other technological assistance) makes it so that we acquire information without knowing, or if it makes it so we do not know how to do what we do as a result of the technological assistance, then we have thereby reduced our ability to succeed in ways important to our humanity. Further, knowledge is arguably required for moral action. Performing a charitable act in full knowledge (and knowing how to perform the act) is more praiseworthy than performing the act in ignorance. If, however, our reliance on new technology diminishes our ability to act knowledgably, then we are less praiseworthy for having relied on that technology. Alden B. Dow is remembered today as a talented architect who adapted Wrightian principles to design modern homes for the midcentury good life, many in his hometown of Midland, Michigan. But Dow was also a prolific amateur filmmaker who ultimately wished to be remembered as a philosopher (fig. 1). Some of his better-known films include two made at Wright’s Taliesin—a black and white film, shot during Dow’s apprenticeship with the master in 1933 and a stunning Kodachrome film of a 1946 trip with his wife to Taliesin West in Arizona, featuring rare footage of Wright himself (fig. 2). These films, which have circulated largely in the service of Wright’s fame as an architect, theorist, and teacher, are just a tiny fraction of the approximately three hundred films produced by Alden Dow from 1923 through the 1960s: travel films and home movies, but also philosophically-oriented experimental films and a host of architectural films. To honor Dow’s legacy and career, some of them are regularly screened today in a small 16mm theater of the architect’s own design in the basement of the Alden B. Dow Home and Studio in Midland, Michigan, as part of that institution’s public outreach and educational mission. Preserved in the archive, the films survive to exemplify the singular creative vision and, yes, philosophy of their maker.

Alden B. Dow is remembered today as a talented architect who adapted Wrightian principles to design modern homes for the midcentury good life, many in his hometown of Midland, Michigan. But Dow was also a prolific amateur filmmaker who ultimately wished to be remembered as a philosopher (fig. 1). Some of his better-known films include two made at Wright’s Taliesin—a black and white film, shot during Dow’s apprenticeship with the master in 1933 and a stunning Kodachrome film of a 1946 trip with his wife to Taliesin West in Arizona, featuring rare footage of Wright himself (fig. 2). These films, which have circulated largely in the service of Wright’s fame as an architect, theorist, and teacher, are just a tiny fraction of the approximately three hundred films produced by Alden Dow from 1923 through the 1960s: travel films and home movies, but also philosophically-oriented experimental films and a host of architectural films. To honor Dow’s legacy and career, some of them are regularly screened today in a small 16mm theater of the architect’s own design in the basement of the Alden B. Dow Home and Studio in Midland, Michigan, as part of that institution’s public outreach and educational mission. Preserved in the archive, the films survive to exemplify the singular creative vision and, yes, philosophy of their maker. In 1844, a Nashville gentleman named Return Jonathan Meigs was placidly reading Francis Bacon in the evening when he suddenly slammed the book shut and, in the presence of his startled fourteen-year-old son,

In 1844, a Nashville gentleman named Return Jonathan Meigs was placidly reading Francis Bacon in the evening when he suddenly slammed the book shut and, in the presence of his startled fourteen-year-old son,  For years I’ve interacted with people who seem to agree with me on the issues—the government should fund technology policy, nuclear energy is good, not bad, economic growth can drive positive-sum improvements for humans and nature, environmental activists are kind of full of shit—but who, when pressed, stop short of fully endorsing ecomodernism as a philosophy or a project. And while we at the Breakthrough Institute have done our best to set up ecomodernism as a “big tent,” inclusive of all sorts of ideological backgrounds and merely “ecomodern-ish” folks, many of these people have left me puzzled. Even discounting the fact that most people will not take as enthusiastically to ecomodernism as I do, it just seems obvious to me that many more of these people should get on board than have done so to date.

For years I’ve interacted with people who seem to agree with me on the issues—the government should fund technology policy, nuclear energy is good, not bad, economic growth can drive positive-sum improvements for humans and nature, environmental activists are kind of full of shit—but who, when pressed, stop short of fully endorsing ecomodernism as a philosophy or a project. And while we at the Breakthrough Institute have done our best to set up ecomodernism as a “big tent,” inclusive of all sorts of ideological backgrounds and merely “ecomodern-ish” folks, many of these people have left me puzzled. Even discounting the fact that most people will not take as enthusiastically to ecomodernism as I do, it just seems obvious to me that many more of these people should get on board than have done so to date. American culture feels dangerously stuck and stilted these days. Many of our best and brightest look for all the world as if they were standing at the tail end of something, equipped with resources fit for a bygone reality, at loose ends in this one. In a perfect bit of performance poetry—who says mass societies can’t be poetical?—we keep cycling through the halls of leadership a cast of tottering, familiar, reassuring grandparents, who spend their tenures insider-trading and murmuring hits from the old boomer songbook, desperately hoping that no cameras are running when they nod off, just a skosh, into their salad, or tip over their mountain bikes, ever so gingerly. Our president turns eighty in November, and he is vowing to run again. We have no new ideas for America. The best in our culture lack all conviction, while the worst are full of passionate intensity (approximately). A soft apocalypticism seems to be in the water.

American culture feels dangerously stuck and stilted these days. Many of our best and brightest look for all the world as if they were standing at the tail end of something, equipped with resources fit for a bygone reality, at loose ends in this one. In a perfect bit of performance poetry—who says mass societies can’t be poetical?—we keep cycling through the halls of leadership a cast of tottering, familiar, reassuring grandparents, who spend their tenures insider-trading and murmuring hits from the old boomer songbook, desperately hoping that no cameras are running when they nod off, just a skosh, into their salad, or tip over their mountain bikes, ever so gingerly. Our president turns eighty in November, and he is vowing to run again. We have no new ideas for America. The best in our culture lack all conviction, while the worst are full of passionate intensity (approximately). A soft apocalypticism seems to be in the water.