by Thomas R. Wells

When people take to the street to protest this is often supposed to be a sign of democracy in action. People who believe that their concerns about the climate change, Covid lockdowns, racism and so on are not being adequately addressed by the political system make a public display of how many of them care a lot about it so that we are all forced to hear about their complaint and our government is put under pressure to address it.

When people take to the street to protest this is often supposed to be a sign of democracy in action. People who believe that their concerns about the climate change, Covid lockdowns, racism and so on are not being adequately addressed by the political system make a public display of how many of them care a lot about it so that we are all forced to hear about their complaint and our government is put under pressure to address it.

But what about this is democratic?

In a democracy we are supposed to accept the outcome of the democratic process, involving reasoned public debate and free electoral competition for positions of public power. The fact that people protest when they don’t accept the outcome of the democratic process is a rather clear sign that protests are a non-democratic activity at best, and at worst an attempt to override and undermine democracy itself. I have in mind particularly the recent climate change related protests in the UK which seem to be spreading and becoming increasingly aggressive, but also recent events like the farmers blocking roads in the Netherlands, the truck drivers blockading Canadian cities and borders, and so on.

At best public protest is non-democratic. It aims to get attention (primarily from the news media) and thus to get the protestors’ complaint higher up in the political agenda – the things the government is expected to have an answer to. Success depends on the quantity of attention the protestors can attract, and this is proportionate to the amount of drama they can cause rather than the quality of their complaint (i.e. its reasonableness). It is thus a kind of democracy hack, like the search engine optimisation companies engage in to get higher on Google’s search results and so get more attention from potential customers. Read more »

Carl Weinberg, in his excellent

Carl Weinberg, in his excellent

Loriel Beltran. P.S.W. 2007-2017

Loriel Beltran. P.S.W. 2007-2017

It’s 6:15 on the Erakor Lagoon in Vanuatu. Women in bright print skirts paddle canoes from villages into town. Yellow-billed birds call from the grass by the water’s edge, roosters crow from somewhere, and the low rumble of the surf hurling itself against the reef is felt as much as heard.

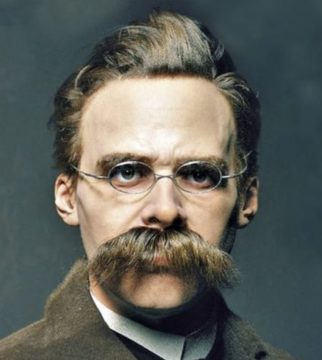

It’s 6:15 on the Erakor Lagoon in Vanuatu. Women in bright print skirts paddle canoes from villages into town. Yellow-billed birds call from the grass by the water’s edge, roosters crow from somewhere, and the low rumble of the surf hurling itself against the reef is felt as much as heard. Should one be altruistic and act for the sake of others, even at a cost to oneself? Should one’s actions be free of any egoistic motivations? Is selflessness a virtue one ought to strive for and cultivate? To many of us the answer to such questions is so self-evident that even raising them would appear to be either a sign of moral obtuseness or an infantile attempt at provocation. For Friedrich Nietzsche, the 19th Century “immoralist” German philosopher, however, the answer to these questions was by no means straightforward and unequivocal. Rather, he believed that altruism and selflessness are neither virtues to be unconditionally pursued and celebrated nor obligations grounded in absolute morality. Moreover, he thought that other-regard (regard for others) is something to be practiced, if at all, with care and moderation; indeed, in some cases selflessness could pose a great danger or even be a sign of deep existential malaise.

Should one be altruistic and act for the sake of others, even at a cost to oneself? Should one’s actions be free of any egoistic motivations? Is selflessness a virtue one ought to strive for and cultivate? To many of us the answer to such questions is so self-evident that even raising them would appear to be either a sign of moral obtuseness or an infantile attempt at provocation. For Friedrich Nietzsche, the 19th Century “immoralist” German philosopher, however, the answer to these questions was by no means straightforward and unequivocal. Rather, he believed that altruism and selflessness are neither virtues to be unconditionally pursued and celebrated nor obligations grounded in absolute morality. Moreover, he thought that other-regard (regard for others) is something to be practiced, if at all, with care and moderation; indeed, in some cases selflessness could pose a great danger or even be a sign of deep existential malaise.

This century has not been kind to human-rights optimists, with 2022 being no exception. Many gains in the recognition and protection of the universal rights recognized in the post-World War II and post-Cold War years have stalled or been eroded. Russia’s criminal behavior in Ukraine is but the most recent example of a broader trend – made even more shocking by Russia’s status as a permanent member of the United Nations Security Council, which exists to uphold the very principles of international law that the Kremlin is now so brazenly violating.

This century has not been kind to human-rights optimists, with 2022 being no exception. Many gains in the recognition and protection of the universal rights recognized in the post-World War II and post-Cold War years have stalled or been eroded. Russia’s criminal behavior in Ukraine is but the most recent example of a broader trend – made even more shocking by Russia’s status as a permanent member of the United Nations Security Council, which exists to uphold the very principles of international law that the Kremlin is now so brazenly violating. My everyday experiences as a chemistry professor at an American university in 2021 bring back memories from my school and university time in the USSR. Not good memories—more like Orwellian nightmares. I will compare my past and present experiences to illustrate the following parallels between the USSR and the US today: (i) the atmosphere of fear and self-censorship; (ii) the omnipresence of ideology (focusing on examples from science); (iii) an intolerance of dissenting opinions (i.e., suppression of ideas and people, censorship, and Newspeak); (iv) the use of social engineering to solve real and imagined problems.

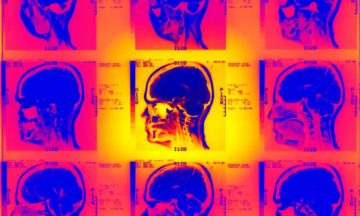

My everyday experiences as a chemistry professor at an American university in 2021 bring back memories from my school and university time in the USSR. Not good memories—more like Orwellian nightmares. I will compare my past and present experiences to illustrate the following parallels between the USSR and the US today: (i) the atmosphere of fear and self-censorship; (ii) the omnipresence of ideology (focusing on examples from science); (iii) an intolerance of dissenting opinions (i.e., suppression of ideas and people, censorship, and Newspeak); (iv) the use of social engineering to solve real and imagined problems. Moheb Costandi’s title is taken from Nietzsche’s philosophical masterpiece Thus Spoke Zarathustra: “The awakened and knowing say: body am I entirely, and nothing more; and soul is only the name for something about the body.” The radical rejection of mind-body dualism expressed in this sentence is shared today by most neuroscientists, who believe that the mind is a product of the brain. Indeed, this “neurocentric” view has been widely accepted and, writes Costandi, “the idea that we are our brains is now firmly established”.

Moheb Costandi’s title is taken from Nietzsche’s philosophical masterpiece Thus Spoke Zarathustra: “The awakened and knowing say: body am I entirely, and nothing more; and soul is only the name for something about the body.” The radical rejection of mind-body dualism expressed in this sentence is shared today by most neuroscientists, who believe that the mind is a product of the brain. Indeed, this “neurocentric” view has been widely accepted and, writes Costandi, “the idea that we are our brains is now firmly established”.