Month: December 2022

Sunday Poem

Asking Questions of the Moon

….. Some blind girls

….. ask questions of the moon

….. and spirals of weeping

….. rise through the air

….. —Federico Garcia Lorca

As a boy, I stood guard in right field, lazily punching my glove,

keeping watch over the ballgame and the moon as it rose

from the infield, asking questions of the moon about the girl

with long blond hair in the back of the classroom, who sat with me

when no one else would, who talked to me when no one else would,

who laughed at my jokes when no one else would, until the day

her friend sat beside us and whispered to her behind that long hair,

and the girl asked me, as softly as she could: Are you a spic?

And I, with a hive of words in my head, could only think to say:

Yes, I am. She never spoke to me again, and as I thought of her

in the outfield, the moon fell from the sky, tore through the webbing

of my glove, and smacked me in the eye. Blinded, I wept, kicked

the moon at my feet, and loudly blamed the webbing of my glove.

by Martín Espada

from Floaters

W.W. Norton & Company, 2021

Trump’s 2024 Campaign So Far Is an Epic Act of Self-Sabotage

Susan Glasser in The New Yorker:

The official campaign for the 2024 Republican Presidential nomination is barely three weeks old, but there is one clear takeaway so far: Donald Trump is running against himself—and losing. From his low-energy announcement speech at Mar-a-Lago to his dinner with the Hitler-praising Kanye West and the white supremacist Nick Fuentes, Trump has courted more controversy than votes since launching his bid in November. He has held no campaign rallies and hired no campaign manager. He has hosted a QAnon conspiracy theorist and helped raise money for the indicted insurrectionists of January 6th. More classified items have been found in his possession, and his Trump Organization was convicted in New York of a major tax-fraud scheme. He has scared away neither prospective opponents nor prosecutors, and, while openly courting extremists, he seems to be running on a campaign platform that is somehow even more nakedly driven by self-interest than his previous two bids. Just last week, he suggested jettisoning the Constitution so he could be reinstated to the office he was thrown out of by the voters in 2020. “A Massive Fraud of this type and magnitude allows for the termination of all rules, regulations, and articles, even those found in the Constitution,” he wrote in a post on his social network, Truth Social.

The official campaign for the 2024 Republican Presidential nomination is barely three weeks old, but there is one clear takeaway so far: Donald Trump is running against himself—and losing. From his low-energy announcement speech at Mar-a-Lago to his dinner with the Hitler-praising Kanye West and the white supremacist Nick Fuentes, Trump has courted more controversy than votes since launching his bid in November. He has held no campaign rallies and hired no campaign manager. He has hosted a QAnon conspiracy theorist and helped raise money for the indicted insurrectionists of January 6th. More classified items have been found in his possession, and his Trump Organization was convicted in New York of a major tax-fraud scheme. He has scared away neither prospective opponents nor prosecutors, and, while openly courting extremists, he seems to be running on a campaign platform that is somehow even more nakedly driven by self-interest than his previous two bids. Just last week, he suggested jettisoning the Constitution so he could be reinstated to the office he was thrown out of by the voters in 2020. “A Massive Fraud of this type and magnitude allows for the termination of all rules, regulations, and articles, even those found in the Constitution,” he wrote in a post on his social network, Truth Social.

The fact that he actually put his objections to the Constitution in writing is a classically Trumpian flourish—one that seems more likely to be used against him in a court of law than to win him any support.

More here.

The Long American Counter-Revolution

David Waldstreicher in Boston Review:

David Waldstreicher in Boston Review:

U.S. history is a strange, exceptional field of play where, to paraphrase Garrison Keillor’s famous sign-off from Lake Wobegon, all the revolutions are strong, all the revolutionaries are kind, and even the civil wars are above average.

In the orthodox telling, there was only one revolution that mattered, after all. The fact that American revolutionaries won their independence in part because the French intervened in their British civil war has often been narrated as at most a useful irony. Certainly Africans or Natives had nothing to do with it, except as desperate fighters for their own marginal purposes: defined out of the story partly because they lost but mostly because, well, they were defined out of the story. Yet the century-long debate between “Progressive” (read: radical) versus “Whig” (liberal and conservative) historians about whether ordinary white people benefitted or whether elites did has begun to seem almost beside the point: there was more at stake for others than republicanism or nationhood.

The certainty that “the people” and their liberties triumphed and set the stage for future progress doesn’t seem sufficient as history anymore. Casting the U.S. Civil War as a second good revolution—a resolution of unfinished business that finally ended slavery (how stubborn it proved!) and created a real nation-state—leaves many questions unanswered. If Revolutionary-era ideas and Civil War identities are so powerful and bend so decisively toward justice, why are the wrong ones winning? No wonder the settler revolutionaries of 1776 realized that the first priority was spin—or as Thomas Jefferson put it so delicately in the Declaration of Independence, “a decent respect for the opinions of mankind.”

More here.

The Respect for Marriage Act Sets a Dangerous Precedent for Civil Rights

Katherine Franke in The Nation (Photo by Jim Watson / AFP via Getty Images):

Katherine Franke in The Nation (Photo by Jim Watson / AFP via Getty Images):

State legislatures across the country put a target on the backs of LGBTQ people this year. Lawmakers introduced nearly 200 bills that would criminalize the health care LGBTQ people need and deserve, erase our history and culture, and render our very existence unspeakable. So, it came as somewhat of a surprise that the US Senate, and now the US House, passed a bill to secure marriage rights for same-sex couples. The Respect for Marriage Act requires the federal government to recognize the marriages of same-sex couples, and mandates that all states honor valid marriages from other states—specifically barring states from refusing to validate out-of-state marriages if the reason for doing so is the couple’s sex, race, ethnicity, or national origin. The bill now heads to President Biden for his signature.

The bill has an unusual provenance. When the Supreme Court overruled Roe v. Wade last June in Dobbs v. Whole Women’s Health, Justice Clarence Thomas wrote a concurrence that made explicit what was implied in Justice Alito’s majority opinion: By knocking the constitutional legs out from under the right to abortion, the court left nothing for the rights to contraception and same-sex marriage to stand on.

More here.

Geopolitics is for losers

Harold James in Aeon:

Today everyone talks geopolitics. The idea is infectious. It appears to come from nowhere. Twenty years ago, the term was exotic, and the meaning behind it quaint. The world was different then. In 2002, America Unrivaled – a book edited by my Princeton colleague, G John Ikenberry, the foremost exponent of the idea of liberal internationalism – asked why there was so little resistance from other countries to American power projection. That was when the momentum in the United States for an attack on Iraq was building up. The contributors argued that there was no balancing against the unipolar moment that had been created with the disintegration of the Soviet Union: in short, no geopolitics. That changed in the course of the 2000s, and the word ‘geopolitics’ began its road to a dominance of political discourse.

There are simple numerical indicators (see Figure 1 below). A compilation of all newspaper uses of ‘geopolitics’ in English-language publications shows a remarkable increase, in two surges, one after the 2007-08 global financial crisis, and the second after 2014-15, in the aftermath of Russia’s annexation of Crimea and the European refugee crisis that followed the Syrian war.

More here.

Money and the Climate Crisis

Mona Ali , Anna Gelpern, Avinash Persaud, Rishikesh Ram Bhandary, Brad Setser, and Adam Tooze in Phenomenal World’s The Polycrisis:

Mona Ali , Anna Gelpern, Avinash Persaud, Rishikesh Ram Bhandary, Brad Setser, and Adam Tooze in Phenomenal World’s The Polycrisis:

The conclusion of COP27 reflected persisting uncertainties around coordinated global action towards decarbonization. Major agreements—including the establishment of a loss and damage fund—were reached, but the burden of mounting debt among global South countries continued to limit climate ambition.

The second event convened by The Polycrisis begins with COP27 and tackles the larger constraints in the global financial system, the role of private finance and multilateral development banks, the possibilities of debt restructuring, and new avenues to rethink climate finance. The discussion featured Mona Ali, Rishikesh Ram Bhandary, Anna Gelpern, Avinash Persaud, and Brad Setser, and was moderated by Adam Tooze.

A recording of the event can be viewed here. This transcript has been lightly edited for length and clarity.

A conversation on climate and the global financial architecture

ADAM TOOZE: It seems to me that there are four key issues for us to discuss. The first is the question of sovereign debt restructuring. Looming over that is the role of private finance in addressing development issues, and climate finance issues in particular. Then there is the role of multinational financial institutions: the World Bank and the IMF. But the obvious place to start is with COP27, and where we’re at now.

Avinash, from your point of view, where do things stand, particularly with the Bridgetown Initiative? You and Barbados Prime Minister Mia Mottley have developed this clearly formulated program for a route out of the impasse we find ourselves in.

More here.

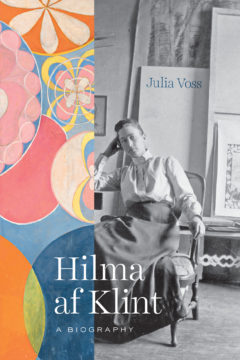

Hilma af Klint: The Painter As A Mystic

Madoc Cairns at The Guardian:

The voices in her head told Hilma af Klint she would be a great artist. They weren’t wrong. Born in 1862, she was unusual from an early age. Growing up in austere Lutheran Sweden, Af Klint studied art at university: a rare feat for a woman. Even less common was her insistence on practising as a professional after graduation. In the face of a society – and an art world – riddled with extreme misogyny, a quiet, conventional career in portraiture seemed the best she could hope for. But then, as Julia Voss reveals in her new biography, Af Klint started to receive messages from another world – and her life in this one was irrevocably altered.

The voices in her head told Hilma af Klint she would be a great artist. They weren’t wrong. Born in 1862, she was unusual from an early age. Growing up in austere Lutheran Sweden, Af Klint studied art at university: a rare feat for a woman. Even less common was her insistence on practising as a professional after graduation. In the face of a society – and an art world – riddled with extreme misogyny, a quiet, conventional career in portraiture seemed the best she could hope for. But then, as Julia Voss reveals in her new biography, Af Klint started to receive messages from another world – and her life in this one was irrevocably altered.

In 1906, she began the construction of an extraordinary series of 1,200 paintings, which she continued until her death in 1944. Reproduced in colour in Voss’s book, the work is still novel, a century or so on. Which wouldn’t have surprised Af Klint. Her visions told her that she was making art for people of the future.

more here.

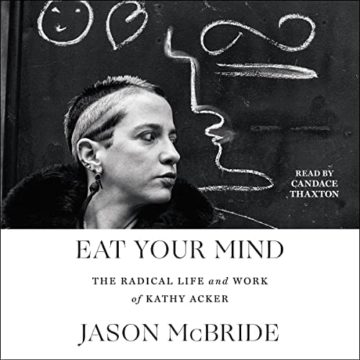

New Biography Of Kathy Acker

Dwight Garner at the NYT:

Kathy Acker — proto-punk, tough-stemmed flower, ransacker of texts, literary heir to William S. Burroughs and Gertrude Stein, sex worker, loather of establishments, striver for maximum impudence — was born into a soft life on Manhattan’s East Side in 1947.

Kathy Acker — proto-punk, tough-stemmed flower, ransacker of texts, literary heir to William S. Burroughs and Gertrude Stein, sex worker, loather of establishments, striver for maximum impudence — was born into a soft life on Manhattan’s East Side in 1947.

Her father’s last name was Lehman, but she didn’t know that until she was grown. Her mother raised her with a stepfather whose surname was Alexander. The name on her birth certificate was Karen, but everyone called her Kathy.

The Alexanders kept poodles and dined together every night. There were private schools, a beach house on Long Island, summer camps in Maine. In high school Kathy was president of the U.N. club. She was presented as a debutante. Though she would struggle financially as an adult, she always wrote with a Montblanc fountain pen. Later she came into a trust fund.

more here.

Kathy Acker At The ICA, 1986

Saturday Poem

Ode to the Soccer Ball Sailing Over a

Barbed-Wire Fence

…….. Tornillo. Has become the symbol of what may be the longest U.S. mass

……. detention of children not charged with crimes since the World War II

…….. internment of Japanese Americans. —Robert Moore, Texas Monthly

Praise Tornillo: word for screw in Spanish, word for jailer in English,

word for three thousand adolescent migrants incarcerated in a camp.

Praise the three thousand soccer balls gift-wrapped at Christmas,

as if raindrops in the desert inflated and bounced through the door.

Priase the soccer games rotating with a whistle every twenty minutes,

so three thousand adolescent migrants could take turns kicking a ball.

Priase the boys and girls who walked a thousand miles, blood caked

in their toes, yelling in Spanish and a dozen Mayan tongues on the field.

Praise the first teenager, brain ablaze like chili pepper Christmas lights,

to kick a soccer ball high over the chain-link and barbed wire-fence.

Praise the first teenager to scrawl a name and number on the face

of the ball, then boot it all the way to the dirt road on the other side.

Praise the smirk of teenagers at the jailer scooping up fugitive

soccer balls, jabbering about the ingratitude of teenagers at Christmas.

Praise the soccer ball sailing over the barbed-wire fence, white

and black like the moon, yellow like the sun, blue like the world.

Praise the soccer ball fling to the moon, flying to the sun, flying to other

worlds, flying to Antigua, where Starbucks buys coffee beans.

Praise the soccer ball bounding off the lawn at the White House,

thudding off the president’s head as he waves to absolutely no one.

Praise the piñata of the president’s head jellybeans pouring from his ears,

enough to feed three thousand adolescents incarcerated at Tornillo.

Praise Tornillo: word in spanish for adolescent migrant internment camp,

abandoned by jailers in the desert, liberated by a blizzard of soccer balls.

by Martín Espada

from Floaters

W.W. Norton, 2021

Cells: Memories for My Mother

Anthony Cummins in The Guardian:

The Irish writer Gavin McCrea was supposed to be writing the third in a loose trilogy of novels about the development of communism, following Mrs Engels (2015), told in the voice of Friedrich Engels’s Irish wife, Lizzie Burns, and The Sisters Mao (2021), set in China and London during the 60s and 70s. By his own account in an interview last year, the next book will run from the fall of the Berlin Wall to the 2008 financial crash. But it got put on hold when, in February 2020, McCrea was the target of homophobic street violence while walking home. The painful memories that the attack stirred brought the structure of a memoir pouring out of him during a late-night writing session and he had no choice but to carry on.

The Irish writer Gavin McCrea was supposed to be writing the third in a loose trilogy of novels about the development of communism, following Mrs Engels (2015), told in the voice of Friedrich Engels’s Irish wife, Lizzie Burns, and The Sisters Mao (2021), set in China and London during the 60s and 70s. By his own account in an interview last year, the next book will run from the fall of the Berlin Wall to the 2008 financial crash. But it got put on hold when, in February 2020, McCrea was the target of homophobic street violence while walking home. The painful memories that the attack stirred brought the structure of a memoir pouring out of him during a late-night writing session and he had no choice but to carry on.

…Cells opens when McCrea returns to Dublin from a spell living abroad late in 2019. The advent of the pandemic adds an unforeseen dimension to his decision to stay and look after his widowed mother, a former care home worker who is becoming increasingly forgetful; under locked-down chit-chat about crosswords and vegetarian meals, he seethes with unlanced resentment that she didn’t do more when he was the victim of homophobic bullying at high school in the 1990s.

McCrea divides the narrative into seven episodes ranging fluently in time via nested memories told with reference to psychoanalysis (“According to Carl Jung… As Freud says…”) and art (the title refers, among other things, to Louise Bourgeois’s work of the same name). He writes with arresting precision, whether he’s introducing us to his mother’s flat (“There are 15 steps up, covered in an old carpet of beige, mauve, burgundy, and blue stripes… After six steps, I am in the seating area, which consists of three ill-matching bits of furniture”) or recounting a recurring dream about wetting himself in the presence of his agent’s son.

More here.

Study of Millions Finds Genetic Links to Smoking and Drinking

Katherine Irving in The Scientist:

A study surveying more than 3.4 million people has found nearly 4,000 genetic variants related to the use of alcohol and tobacco, scientists reported Wednesday (Dec 7) in Nature. More than 1,900 of the variants had not previously been linked to substance use behaviors, study coauthor and statistical geneticist at the Penn State College of Medicine Dajiang Liu states in a press release. The novel findings were aided by the fact that a fifth of the genomic samples came from individuals of non-European ancestry, Liu says.

A study surveying more than 3.4 million people has found nearly 4,000 genetic variants related to the use of alcohol and tobacco, scientists reported Wednesday (Dec 7) in Nature. More than 1,900 of the variants had not previously been linked to substance use behaviors, study coauthor and statistical geneticist at the Penn State College of Medicine Dajiang Liu states in a press release. The novel findings were aided by the fact that a fifth of the genomic samples came from individuals of non-European ancestry, Liu says.

“This is a great study. It demonstrates the power of using large samples from multiple ancestry groups in well-designed analyses,” geneticist and neuroscientist Joel Gelernter of Yale University tells New Scientist.

Although scientists have conducted similar genome-wide association studies (GWAS) in the past, Liu tells New Scientist that the majority of those surveys were conducted primarily on people of European descent. Although social situations and policies may influence a person’s inclination towards smoking and drinking, there is substantial evidence that a person’s genetic makeup may also predispose them towards alcohol and tobacco usage. “We’re at a stage where genetic discoveries are being translated into clinical [applications],” Liu tells Nature. “If we can forecast someone’s risk of developing nicotine or alcohol dependence using this information, we can intervene early and potentially prevent a lot of deaths.”

More here.

Can AI Write Authentic Poetry?

Keith Holyoak at The MIT Press Reader:

Artificial intelligence (AI) is in the process of changing the world and its societies in ways no one can fully predict. On the hazier side of the present horizon, there may come a tipping point at which AI surpasses the general intelligence of humans. (In various specific domains, notably mathematical calculation, the intersection point was passed decades ago.) Many people anticipate this technological moment, dubbed the Singularity, as a kind of Second Coming — though whether of a savior or of Yeats’s rough beast is less clear. Perhaps by constructing an artificial human, computer scientists will finally realize Mary Shelley’s vision.

Artificial intelligence (AI) is in the process of changing the world and its societies in ways no one can fully predict. On the hazier side of the present horizon, there may come a tipping point at which AI surpasses the general intelligence of humans. (In various specific domains, notably mathematical calculation, the intersection point was passed decades ago.) Many people anticipate this technological moment, dubbed the Singularity, as a kind of Second Coming — though whether of a savior or of Yeats’s rough beast is less clear. Perhaps by constructing an artificial human, computer scientists will finally realize Mary Shelley’s vision.

Of all the actual and potential consequences of AI, surely the least significant is that AI programs are beginning to write poetry. But that effort happens to be the AI application most relevant to our theme. And in a certain sense, poetry may serve as a kind of canary in the coal mine — an early indicator of the extent to which AI promises (threatens?) to challenge humans as artistic creators. If AI can be a poet, what other previously human-only roles will it slip into?

More here.

Why the laws of physics don’t actually exist

Sankar Das Sarma in New Scientist:

I was recently reading an old article by string theorist Robbert Dijkgraaf in Quanta Magazine entitled “There are no laws of physics”. You might think it a bit odd for a physicist to argue that there are no laws of physics but I agree with him. In fact, not only do I agree with him, I think that my field is all the better for it. And I hope to convince you of this too.

I was recently reading an old article by string theorist Robbert Dijkgraaf in Quanta Magazine entitled “There are no laws of physics”. You might think it a bit odd for a physicist to argue that there are no laws of physics but I agree with him. In fact, not only do I agree with him, I think that my field is all the better for it. And I hope to convince you of this too.

First things first. What we often call laws of physics are really just consistent mathematical theories that seem to match some parts of nature. This is as true for Newton’s laws of motion as it is for Einstein’s theories of relativity, Schrödinger’s and Dirac’s equations in quantum physics or even string theory. So these aren’t really laws as such, but instead precise and consistent ways of describing the reality we see. This should be obvious from the fact that these laws are not static; they evolve as our empirical knowledge of the universe improves.

Here’s the thing. Despite many scientists viewing their role as uncovering these ultimate laws, I just don’t believe they exist.

More here.

Taika Waititi reads a hilarious letter about a speeding ticket

The Long American Counter-Revolution

David Waldstreicher in the Boston Review:

In the orthodox telling, there was only one revolution that mattered, after all. The fact that American revolutionaries won their independence in part because the French intervened in their British civil war has often been narrated as at most a useful irony. Certainly Africans or Natives had nothing to do with it, except as desperate fighters for their own marginal purposes: defined out of the story partly because they lost but mostly because, well, they were defined out of the story. Yet the century-long debate between “Progressive” (read: radical) versus “Whig” (liberal and conservative) historians about whether ordinary white people benefitted or whether elites did has begun to seem almost beside the point: there was more at stake for others than republicanism or nationhood.

In the orthodox telling, there was only one revolution that mattered, after all. The fact that American revolutionaries won their independence in part because the French intervened in their British civil war has often been narrated as at most a useful irony. Certainly Africans or Natives had nothing to do with it, except as desperate fighters for their own marginal purposes: defined out of the story partly because they lost but mostly because, well, they were defined out of the story. Yet the century-long debate between “Progressive” (read: radical) versus “Whig” (liberal and conservative) historians about whether ordinary white people benefitted or whether elites did has begun to seem almost beside the point: there was more at stake for others than republicanism or nationhood.

The certainty that “the people” and their liberties triumphed and set the stage for future progress doesn’t seem sufficient as history anymore.

More here.

The Work of Irving Babbitt with Michael P. Federici

Michael Heizer’s ‘City’: A Visit to a Ruin Being Born

Kirsten Swenson at Art in America:

The trip to Michael Heizer’s City begins in a city: Las Vegas, city of neon and glass, concrete and gravel. I cannot think about City without reference to its nearest desert metropolis, where water and social safety nets are in short supply. Most visitors to City will begin here. But to experience Land art is not simply to show up at a destination. It is a journey, a series of encounters with different landscapes and the systems that operate in and around them.

The trip to Michael Heizer’s City begins in a city: Las Vegas, city of neon and glass, concrete and gravel. I cannot think about City without reference to its nearest desert metropolis, where water and social safety nets are in short supply. Most visitors to City will begin here. But to experience Land art is not simply to show up at a destination. It is a journey, a series of encounters with different landscapes and the systems that operate in and around them.

City has been on my mind since the early 2000s and my first visit to Heizer’s Double Negative (1969) for a Land art seminar I taught at the University of Nevada, Las Vegas. To experience that work, a visitor descends into deep notches blasted from a mesa about 60 miles northeast of Las Vegas, passing between ragged sandstone walls to emerge from the cut and take in sweeping views of the Virgin River Valley. Anyone can visit Double Negative, of which Heizer has said, “There is nothing there, yet it is still a sculpture.”

more here.

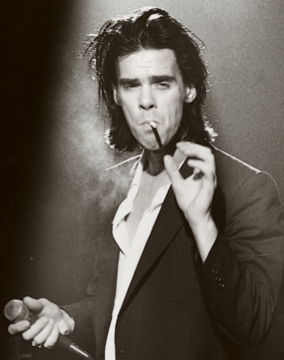

Nick Cave

Kate Mossman and Nick Cave at The New Statesman:

The former Archbishop of Canterbury, Rowan Williams, recently selected Faith, Hope and Carnage as his New Statesman book of the year. I asked him why he found it particularly moving. “There are various familiar ways of putting together the language of faith and the experience of appalling suffering,” he told me. “Some people simply treat faith as consolation: things look terrible but it’s going to turn out fine. Others say that the experience of atrocity negates all possible reference to the sacred or the divine. Nick Cave refuses both sorts of simplicity. For him, the extremity of pain and loss releases something; it pushes you over the edge of whatever limits you had taken for granted and uncovers a kind of imaginative energy, not always welcome.”

The former Archbishop of Canterbury, Rowan Williams, recently selected Faith, Hope and Carnage as his New Statesman book of the year. I asked him why he found it particularly moving. “There are various familiar ways of putting together the language of faith and the experience of appalling suffering,” he told me. “Some people simply treat faith as consolation: things look terrible but it’s going to turn out fine. Others say that the experience of atrocity negates all possible reference to the sacred or the divine. Nick Cave refuses both sorts of simplicity. For him, the extremity of pain and loss releases something; it pushes you over the edge of whatever limits you had taken for granted and uncovers a kind of imaginative energy, not always welcome.”

Cave’s book is perhaps unique in drawing connections between faith, grief and creativity. His God “lives here”, Williams told me, “where the God of the Book of Job or of Elie Wiesel or Dostoevsky lives, not consoling but overwhelming and generating. Not a rationale for suffering or an excuse for looking away but a resource for standing in the middle of it all without complete disintegration of mind and heart.”

more here.