by Tim Sommers

I try to keep callbacks to a minimum in my columns here, but this one seems worth it. Be warned, though. It’s well into the weeds we go.

Last month, right here, I posted this piece.

“Are Counterfeit People the Most Dangerous Artifacts in Human History?”

It was a counter to Daniel Dennett’s recent piece in The Atlantic, “The Problem with Counterfeit People.”

As I wrote later in an email to Dennett, “I really only wanted to make two points in the article. (1) I worry that framing the issue as being about ‘counterfeit’ people deflects from the fact that, in my humble opinion, all the real harms [you cite] don’t require anything like ‘real’ AI – and they are mostly already here. (2) Probably, I am wrong (a lot of people seem to think so), but I also thought it was a weird way for you to frame the issue as I thought the intentional stance didn’t leave as much room as more conventional thinking about the mind for there to be a real/fake distinction.”

Much to my surprise our illustrious Webmaster S. Abbas Raza, who is a friend of Dennett’s, passed the piece along to him.

Dennett initially responded by forwarding a few links. I thought, surely, that is worth sharing. So, here they are.

“Two models of AI oversight – and how things could go deeply wrong” by Gary Marcus.

(Marcus features in my previous piece “Artificial General What?”)

He also sent this https://www.cnn.com/2023/06/08/tech/ai-image-detection/index.html, and this

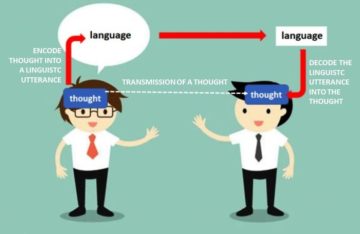

“Language Evolution and Direct vs Indirect Symbol Grounding,” by Steven Harnad.

Later Dennett wrote, “The main point I should have made in response to your piece…is that LLMs aren’t persons, lacking higher order desires (see ‘conditions of personhood’) and hence are dangerous. There is no reason to trust them for instance but few will be able to resist. They are high tech memes that can evolve independently of any human control.”

I thought it would be fun to have my friend and colleague Farhan Lakhany, who is something of an expert on Dennett’s work and philosophy of mind in general, take an objective look at the exchange. Lakhany just successfully defended his Ph.D, Representing Qualia: An Epistemic Path out of the Hard Problem at the University of Iowa so I thought it would be great to have him agree with me that I am right. He did not. Here’s what he said. Read more »

Boomer-bashing is everywhere. Maybe it’s warranted, but a reality check is in order, because the bashing starts from an easy and false idea about how power has moved in American society. The recent change in House Democratic leadership is almost too perfect an example. As a “new generation” takes power in the top three offices, we quietly ignore the most interesting generational story. We griped about the old guard clinging to power, and we cheer for our new young leaders, but we don’t mention that political power skipped a generation: it passed from the pre-Baby Boom generation to the post-Baby Boom generation. The Boomers themselves were shut out of power. As usual.

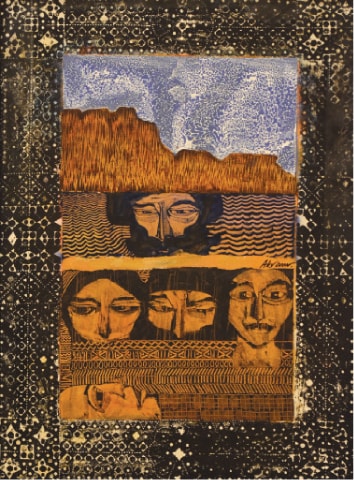

Boomer-bashing is everywhere. Maybe it’s warranted, but a reality check is in order, because the bashing starts from an easy and false idea about how power has moved in American society. The recent change in House Democratic leadership is almost too perfect an example. As a “new generation” takes power in the top three offices, we quietly ignore the most interesting generational story. We griped about the old guard clinging to power, and we cheer for our new young leaders, but we don’t mention that political power skipped a generation: it passed from the pre-Baby Boom generation to the post-Baby Boom generation. The Boomers themselves were shut out of power. As usual. Akram Dost Baloch. From the exhibition “Identities”, 2020.

Akram Dost Baloch. From the exhibition “Identities”, 2020.

There may be no concept so alluring in all of science fiction than that of time travel. We are undoubtedly drawn to alien species and places in space—moons to colonize, asteroids to mine. But even freakish beings and far-off worlds, however remote, have always smacked a little too much of our own reality. I’m fully capable, after all, of walking from my apartment to the park. I can sit on a bench and read

There may be no concept so alluring in all of science fiction than that of time travel. We are undoubtedly drawn to alien species and places in space—moons to colonize, asteroids to mine. But even freakish beings and far-off worlds, however remote, have always smacked a little too much of our own reality. I’m fully capable, after all, of walking from my apartment to the park. I can sit on a bench and read

Rebecca F. Kuang

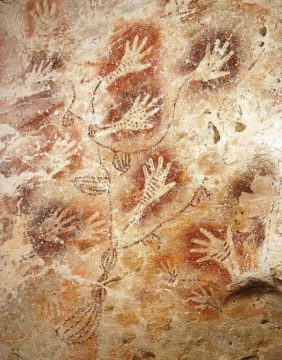

Rebecca F. Kuang First mixing the grounds of red and yellow ocher with water so as to make a viscus, sticky gum which she puts between her cheek and whatever teeth she may have had, the woman placed her rough, calloused, weather-beaten, sun-chapped hand against the nubbly surface of the limestone cave’s wall, and then perhaps using a hollow-reed picked from the silty banks of the Rammang-rammang River she would blow that inky substance through her straw, leaving the shadow of a perfect outline. This happened around forty thousand years ago and her hand is still there. A little over two dozen of these tracings in white and red are all over the cave wall. What she looked like, where she was born, whether she had a partner or children, what gods she prayed to and what she requested will forever be unknown, but her fingers are slim and tapered and impossible to distinguish from those of any modern human. “It may seem something of a gamble to try to get close to the thought processes that guided these people,” writes archeologist Jean Clottes in What is Paleolithic Art?: Cave Paintings and the Dawn of Human Creativity. “They are so remote from us.” Today a ladder must be pushed against the surface of the cave’s exterior, which appears as if a dark mouth over the humid, muddy Indonesian rice fields of South Sulawesi Island, so as to climb inside and examine her compositions, but during the Neolithic perhaps they simply cleaved alongside the rock face with their hands and feet. Several other paintings are in the complex; among the earliest figurative compositions ever rendered, some of the sleek, aquiline, red hog deer, others of chimerical therianthropes that are part human and part animal. Beautiful, obviously, and evocative, enigmatic, enchanting, but those handprints are mysterious and moving in a different way, a tangible statement of identity, of a woman who despite the enormity of all of that which we can never understand about her, still made this piece forty millennia ago that let us know she was here, that she lived.

First mixing the grounds of red and yellow ocher with water so as to make a viscus, sticky gum which she puts between her cheek and whatever teeth she may have had, the woman placed her rough, calloused, weather-beaten, sun-chapped hand against the nubbly surface of the limestone cave’s wall, and then perhaps using a hollow-reed picked from the silty banks of the Rammang-rammang River she would blow that inky substance through her straw, leaving the shadow of a perfect outline. This happened around forty thousand years ago and her hand is still there. A little over two dozen of these tracings in white and red are all over the cave wall. What she looked like, where she was born, whether she had a partner or children, what gods she prayed to and what she requested will forever be unknown, but her fingers are slim and tapered and impossible to distinguish from those of any modern human. “It may seem something of a gamble to try to get close to the thought processes that guided these people,” writes archeologist Jean Clottes in What is Paleolithic Art?: Cave Paintings and the Dawn of Human Creativity. “They are so remote from us.” Today a ladder must be pushed against the surface of the cave’s exterior, which appears as if a dark mouth over the humid, muddy Indonesian rice fields of South Sulawesi Island, so as to climb inside and examine her compositions, but during the Neolithic perhaps they simply cleaved alongside the rock face with their hands and feet. Several other paintings are in the complex; among the earliest figurative compositions ever rendered, some of the sleek, aquiline, red hog deer, others of chimerical therianthropes that are part human and part animal. Beautiful, obviously, and evocative, enigmatic, enchanting, but those handprints are mysterious and moving in a different way, a tangible statement of identity, of a woman who despite the enormity of all of that which we can never understand about her, still made this piece forty millennia ago that let us know she was here, that she lived.

How much you can divide this sentence into similarly incorrect phrases?

How much you can divide this sentence into similarly incorrect phrases?

I have a confession to make: I ❤️ Seymour Glass. If you don’t know who that is, count yourself lucky and walk away now—come back in a few weeks when I’ll be discussing humiliating experiences at middle-school dances or whatever. (Obviously I am joking—as always, I desperately want you to finish reading this essay.)

I have a confession to make: I ❤️ Seymour Glass. If you don’t know who that is, count yourself lucky and walk away now—come back in a few weeks when I’ll be discussing humiliating experiences at middle-school dances or whatever. (Obviously I am joking—as always, I desperately want you to finish reading this essay.)

I’ve mostly escaped the selfie photo culture, not out of some virtuous modesty, but because I generally look like a confused mouth-breathing moron in photos. So selfies are more of an indictment for me than something I want to post on Instagram. If I photographed like a Benicio del Toro or George Clooney, all bets would be off. And before I offend and get canceled by any mouth breathers, I am part of the mouth-breathing family due to a deviated septum. At full rest, I sound like one of those artificial lungs in hospitals.

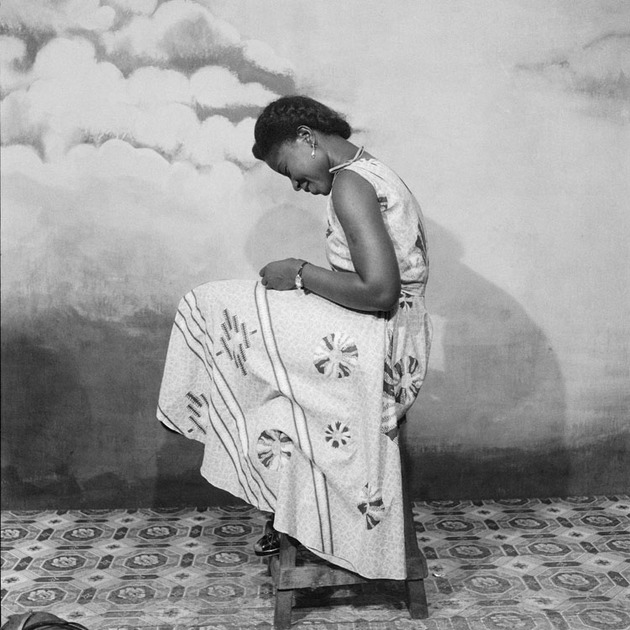

I’ve mostly escaped the selfie photo culture, not out of some virtuous modesty, but because I generally look like a confused mouth-breathing moron in photos. So selfies are more of an indictment for me than something I want to post on Instagram. If I photographed like a Benicio del Toro or George Clooney, all bets would be off. And before I offend and get canceled by any mouth breathers, I am part of the mouth-breathing family due to a deviated septum. At full rest, I sound like one of those artificial lungs in hospitals. James Barnor. Portrait, Accra, ca 1954.

James Barnor. Portrait, Accra, ca 1954. Panic about runaway artificial super-intelligence spiked recently, with doomsayers like

Panic about runaway artificial super-intelligence spiked recently, with doomsayers like