by Andrea Scrima

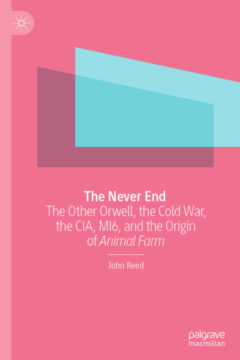

Twenty years ago, John Reed made an unexpected discovery: “If Orwell esoterica wasn’t my foremost interest, I eventually realized that, in part, it was my calling.” In the aftermath of September 11, 2001, ideas that had been germinating suddenly coalesced, and in three weeks’ time Reed penned a parody of George Orwell’s Animal Farm. The memorable pig Snowball would return from exile, bringing capitalism with him—thus updating the Cold War allegory by fifty-some years and pulling the rug out from underneath it. At the time, Reed couldn’t have anticipated the great wave of vitriol and legal challenges headed his way—or the series of skewed public debates with the likes of Christopher Hitchens. Apparently, the world wasn’t ready for a take-down of its patron saint, or a sober look at Orwell’s (and Hitchens’s) strategic turn to the right.

Twenty years ago, John Reed made an unexpected discovery: “If Orwell esoterica wasn’t my foremost interest, I eventually realized that, in part, it was my calling.” In the aftermath of September 11, 2001, ideas that had been germinating suddenly coalesced, and in three weeks’ time Reed penned a parody of George Orwell’s Animal Farm. The memorable pig Snowball would return from exile, bringing capitalism with him—thus updating the Cold War allegory by fifty-some years and pulling the rug out from underneath it. At the time, Reed couldn’t have anticipated the great wave of vitriol and legal challenges headed his way—or the series of skewed public debates with the likes of Christopher Hitchens. Apparently, the world wasn’t ready for a take-down of its patron saint, or a sober look at Orwell’s (and Hitchens’s) strategic turn to the right.

Snowball’s Chance, it turns out, was only the beginning. The book was published the same year as Hitchens’s Why Orwell Matters, and the media frequently paired the two. In the years that followed, Reed wrote a series of essays (published in The Paris Review, Harper’s, The Believer, and other journals) analyzing the heated response to the book and everything it implied. Orwell’s writing had long been used as a propaganda tool, and evidence had emerged that his political leanings went far beyond defaming communism—but if facing this basic historical truth was so unthinkable, what was the taboo preventing us from seeing? Reed’s examination of our Orwell preoccupation sifts through the changes the West has undergone since the Cold War: its cultural crises, its military disasters, its self-deceptions and confusions, and more recently—perhaps even more troubling—its new instability of identity. The Never End brings together nine of these essays and adds an Animal Farm timeline, a footnoted version of Orwell’s proposed preface, and the Russian text Animal Farm originally drew from to more clearly assess the circumstances behind, and the conclusions to be drawn from, the book’s global importance. Read more »

“Martti Ahtisaari, ex-Finland president and Nobel peace laureate, dies aged 86” runs the headline of

“Martti Ahtisaari, ex-Finland president and Nobel peace laureate, dies aged 86” runs the headline of

I once wrote a political column for

I once wrote a political column for

Sughra Raza. Pale Sunday Morning, April 2021.

Sughra Raza. Pale Sunday Morning, April 2021. bankruptcy were billing at $2,165 an hour ($595 for paralegals). Since then we learned:

bankruptcy were billing at $2,165 an hour ($595 for paralegals). Since then we learned:

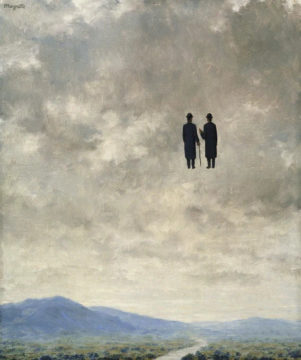

Lightness comes in three F’s: finesse, flippancy and fantasy. The French are famous for the first. See how the delicate, sweet singer songwriter Alain Souchon transforms the heavyweight aphorism of André Malraux – the real-life French Indiana Jones who ended his career as minister for culture – from the desperate heroism of ‘I learnt that a life is worth nothing, but nothing is more valuable than life’ into the ethereal, refined song that even if you do not understand the words, you cannot help but feel the

Lightness comes in three F’s: finesse, flippancy and fantasy. The French are famous for the first. See how the delicate, sweet singer songwriter Alain Souchon transforms the heavyweight aphorism of André Malraux – the real-life French Indiana Jones who ended his career as minister for culture – from the desperate heroism of ‘I learnt that a life is worth nothing, but nothing is more valuable than life’ into the ethereal, refined song that even if you do not understand the words, you cannot help but feel the

In 1970, Pier Paolo Passolini directed a film titled Notes Towards an African Orestes, which presents footage about his attempt to make a movie based on the Oresteia set in Africa. The movie was never made. In the same way, this article will be about a series of essays, or perhaps a book, that may never be written.

In 1970, Pier Paolo Passolini directed a film titled Notes Towards an African Orestes, which presents footage about his attempt to make a movie based on the Oresteia set in Africa. The movie was never made. In the same way, this article will be about a series of essays, or perhaps a book, that may never be written. Without really looking into them, I have always felt sceptical of Kantian approaches to animal ethics. I never really trust them to play well with creatures who are different from us. Only recently, I cared to pick up a book to see what such an approach would actually look like in practice: Christine Korsgaard’s Fellow creatures (2018). An exciting and challenging reading experience, that not only made a very good case for Kantianism (of course), but also forced me to come to terms with some rather strange implications of my own views.

Without really looking into them, I have always felt sceptical of Kantian approaches to animal ethics. I never really trust them to play well with creatures who are different from us. Only recently, I cared to pick up a book to see what such an approach would actually look like in practice: Christine Korsgaard’s Fellow creatures (2018). An exciting and challenging reading experience, that not only made a very good case for Kantianism (of course), but also forced me to come to terms with some rather strange implications of my own views.