That title reads like I have doubts about the current state of affairs in the world of artificial intelligence. And I do – who doesn’t? – but explicating that analogy is tricky, so I fear I’ll have to leave our hapless captain hanging while I set some conceptual equipment in place.

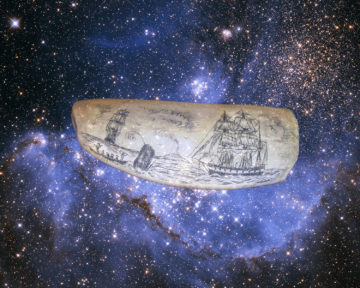

First, I am going to take quick look at how I responded to GPT-3 back in 2020. Then I talk about programs and language, who understands what, and present some Steven Pinker’s reservations about large language models (LLMs) and correlative beliefs in their prepotency. Next, I explain the whaling analogy (six paragraphs worth) followed by my observations on some of the more imaginative ideas of Geoffrey Hinton and Ilya Sutskever. I return to whaling for the conclusion: “we’re on a Nantucket sleighride.” All of us.

This is going to take a while. Perhaps you should gnaw on some hardtack, draw a mug of grog, and light a whale oil lamp to ease the strain on your eyes.

What I Said in 2020: Here be Dragons

GPT-3 was released on June 11 for limited beta testing. I didn’t have access myself, but I was able to play around with it a bit through a friend, Phil Mohun. I was impressed. Here’s how I began paper I wrote at the time:

GPT-3 is a significant achievement.

But I fear the community that has created it may, like other communities have done before – machine translation in the mid-1960s, symbolic computing in the mid-1980s, triumphantly walk over the edge of a cliff and find itself standing proudly in mid-air.

This is not necessary and certainly not inevitable.

A great deal has been written about GPTs and transformers more generally, both in the technical literature and in commentary of various levels of sophistication. I have read only a small portion of this. But nothing I have read indicates any interest in the nature of language or mind. Interest seems relegated to the GPT engine itself. And yet the product of that engine, a language model, is opaque. I believe that, if we are to move to a level of accomplishment beyond what has been exhibited to date, we must understand what that engine is doing so that we may gain control over it. We must think about the nature of language and of the mind.

I still believe that. Read more »

Masjid Al Aqsa, or The Far Mosque of Jerusalem, as the Quran calls it, is emblematic of the spirit of compassion and transcendence for Mevlana Rumi. “A heart sanctuary,” in the words of Rumi in his poem “The Far Mosque,” Al Aqsa represents a conquest over the egoistical desires of dominance, greed, vanity, violence and supremacy. It is held together by the sacred energy of merciful love, even “the carpet bows to the broom/the door knocker and the door swing together/like musicians.”

Masjid Al Aqsa, or The Far Mosque of Jerusalem, as the Quran calls it, is emblematic of the spirit of compassion and transcendence for Mevlana Rumi. “A heart sanctuary,” in the words of Rumi in his poem “The Far Mosque,” Al Aqsa represents a conquest over the egoistical desires of dominance, greed, vanity, violence and supremacy. It is held together by the sacred energy of merciful love, even “the carpet bows to the broom/the door knocker and the door swing together/like musicians.”

In 2016,

In 2016,

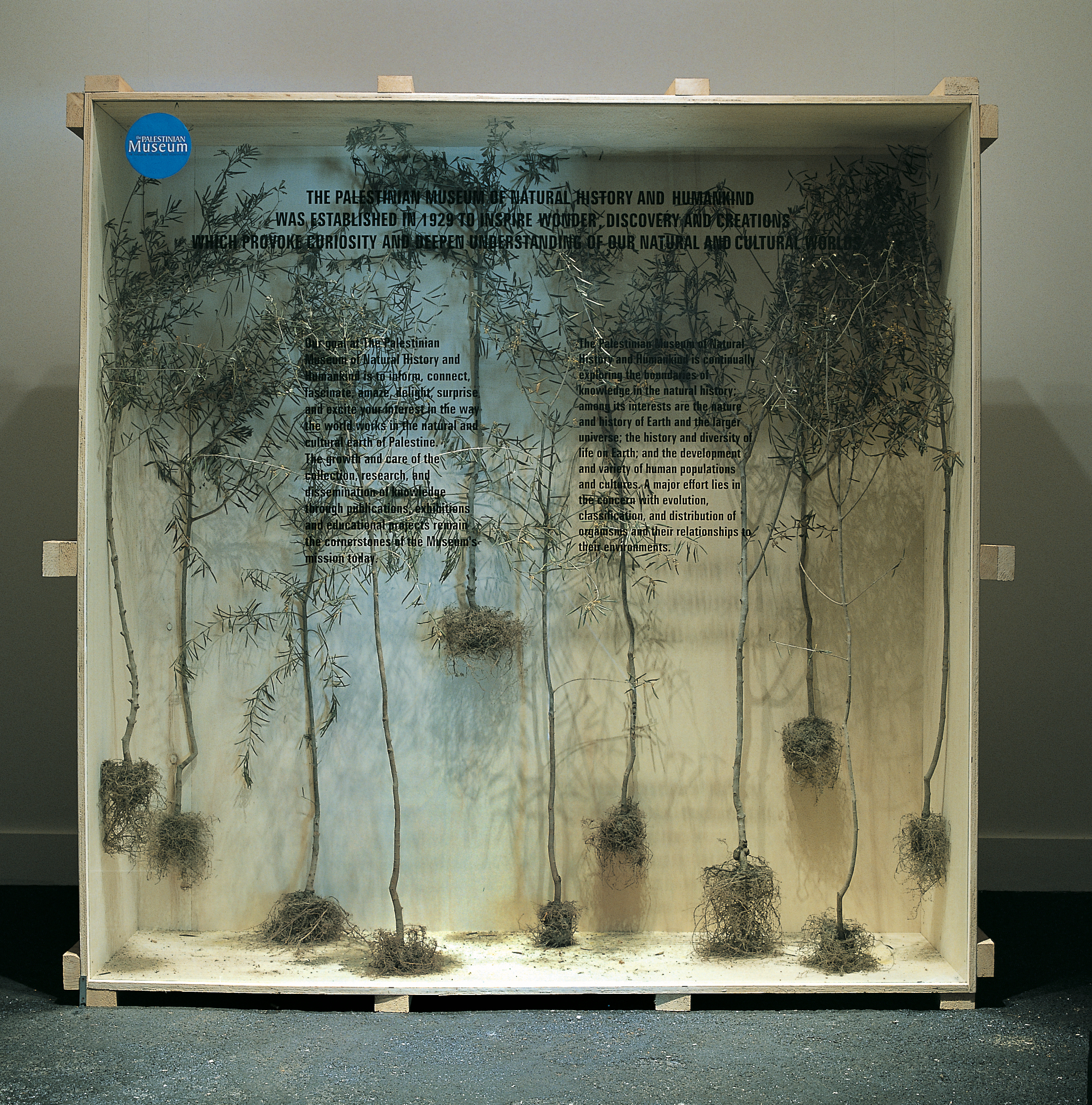

Khalil Rabah. About The Museum, 2004.

Khalil Rabah. About The Museum, 2004.

If a city could be an organism, then Kherson in Eastern Ukraine would be a sick body. For eight months, between March and November 2022, Kherson was occupied by Russian forces. Kidnapping, torture, and murder – in terms of violence and cruelty, Kherson’s citizens have seen it all. Today, even though liberated, the port city on the Dnieper River and the Black Sea is still being regularly bombarded: a children’s hospital, a bus stop, a supermarket. Even though freed, how could this city ever heal?

If a city could be an organism, then Kherson in Eastern Ukraine would be a sick body. For eight months, between March and November 2022, Kherson was occupied by Russian forces. Kidnapping, torture, and murder – in terms of violence and cruelty, Kherson’s citizens have seen it all. Today, even though liberated, the port city on the Dnieper River and the Black Sea is still being regularly bombarded: a children’s hospital, a bus stop, a supermarket. Even though freed, how could this city ever heal?

Two popular books released this year have breathed new life into the ancient debate over whether we have free will.

Two popular books released this year have breathed new life into the ancient debate over whether we have free will. We all naturally take an interest in the night sky. Just last week, my fiancee and I attended an event put on by the Astronomical Society of New Haven. Without a cloud in the sky, near-freezing temperatures, and a new moon, the conditions were ideal for looking through telescopes the size of cannons. To see anything, you had to stand in line, in the cold, for your opportunity to look at something for a minute.

We all naturally take an interest in the night sky. Just last week, my fiancee and I attended an event put on by the Astronomical Society of New Haven. Without a cloud in the sky, near-freezing temperatures, and a new moon, the conditions were ideal for looking through telescopes the size of cannons. To see anything, you had to stand in line, in the cold, for your opportunity to look at something for a minute.