by Chris Horner

if often he was wrong and, at times, absurd,

to us he is no more a person

now but a whole climate of opinion

under whom we conduct our different lives—W. H. Auden ‘In memory of Sigmund Freud’

Undead

Freud and psychoanalysis seem to be in a state resembling Schrodinger’s famous cat: alive and dead at the same time. Dead and discredited and yet alive and influential. Perhaps the better analogy here is not to the ambiguous feline but to another figure: that of the undead. For while Freud the man expired in 1939 and has been killed again and again before and after that date, still he returns, like something repressed that just won’t lie down and vanish.

In an interesting essay in the New Republic in 1995, Jonathan Lear commented on the extraordinary fervour with which Freud and psychoanalysis seemed to be killed, again and again [1]. It prompts the thought: why? Lear proposes three cultural currents that motivate Freud bashing: the development of drugs, alongside increasing knowledge and interest in how the brain works, the way cheap pharmacology seems preferable to expensive psychoanalysis, and finally a backlash against some of the grander claims about Freud and his techniques that were much touted in the earlier part of the last century. Certainly Freud got things wrong and sometimes went about his analysis in a way that seems quite mistaken. But is that it?

Meanings

Meanings

As Lear remarks, at his best Freud is a profound explorer of the human condition. To quote Lear:

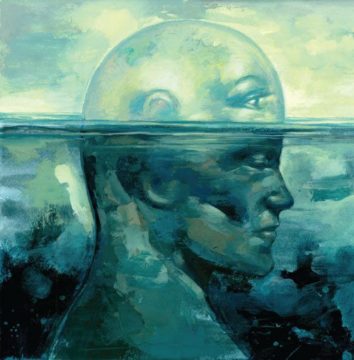

Humans make meaning, for themselves and for others, of which they have no direct or immediate awareness. People make more meaning than they know what to do with. This is what Freud meant by the unconscious. And whatever valid criticisms can be aimed at him or the psychoanalytic profession, it is nevertheless true that psychoanalysis is the most sustained and successful attempt to make these obscure meanings intelligible. [2]

Psychoanalysis is both a mode of treatment and a way of understanding the mind. As a mode of treatment it certainly seemed to many in the 1990s that it had had its day. Apart from some of the hypotheses that seems hard to assess using scientific principles, the long and expensive process of getting someone to just talk about themselves seemed outmoded, given alternative treatments available. Cognitive behavioural treatment (CBT) and the newer drugs of which Prozac became the most well known, seemed to offer a surer path to successful treatment. Except when it didn’t. In 2023 the status of both those alternatives loo a lot less obviously attractive, given the remarkably low rate of success with patients of CBT [3] and of drugs [4]. Both these approaches have their strengths, and can certainly help some people, some of the time. But the same is true of psychoanalysis. Psychoanalysis is lengthy: 18 months seems to be the minimum time for it to have success. Perhaps, then, the lesson is that there are no quick fixes when it comes to helping a human being to become mentally well?

Psychoanalysis is both a mode of treatment and a way of understanding the mind. As a mode of treatment it certainly seemed to many in the 1990s that it had had its day. Apart from some of the hypotheses that seems hard to assess using scientific principles, the long and expensive process of getting someone to just talk about themselves seemed outmoded, given alternative treatments available. Cognitive behavioural treatment (CBT) and the newer drugs of which Prozac became the most well known, seemed to offer a surer path to successful treatment. Except when it didn’t. In 2023 the status of both those alternatives loo a lot less obviously attractive, given the remarkably low rate of success with patients of CBT [3] and of drugs [4]. Both these approaches have their strengths, and can certainly help some people, some of the time. But the same is true of psychoanalysis. Psychoanalysis is lengthy: 18 months seems to be the minimum time for it to have success. Perhaps, then, the lesson is that there are no quick fixes when it comes to helping a human being to become mentally well?

A case can be made for the argument that obsessing on Freud the man is a way of avoiding engaging with the meanings that psychoanalysis investigates. In any case, as Auden noted, he has become a climate of opinion more than just this or that theory, and we use terms that directly or indirectly derive from him all the time: unconscious motives (that there is an unconscious), repression, defence mechanisms, neurotic symptoms, meaning in dreams, trauma and the repetition compulsion, ‘Freudian slips’ and much more. As Richard Boothby remarks, he is the most influential thinker of the 20th century, and his influence is everywhere. [5]

A case can be made for the argument that obsessing on Freud the man is a way of avoiding engaging with the meanings that psychoanalysis investigates. In any case, as Auden noted, he has become a climate of opinion more than just this or that theory, and we use terms that directly or indirectly derive from him all the time: unconscious motives (that there is an unconscious), repression, defence mechanisms, neurotic symptoms, meaning in dreams, trauma and the repetition compulsion, ‘Freudian slips’ and much more. As Richard Boothby remarks, he is the most influential thinker of the 20th century, and his influence is everywhere. [5]

The Man Himself

We can isolate three key phenomena that Freud made central to his work: dreams, parapraxes (those ‘Freudian slips’) and symptoms. It’s not my purpose to discuss these topics and their validity here, but rather to make the point that the development of psychoanalysis, building on Freud, has come a long way since 1939 and deserves to be understood before judgement is passed on it.

As for Freud himself, the best introduction, I think, is to read him yourself. He is clear and more interesting than many of the introductions. My favourite remains his Introductory Lectures [6]. He’s also often his best critic. Like many genuinely creative and honest thinkers he questioned and challenged his own ideas as he went on. The result is, whatever the textbooks may tell you to the contrary, that there is no single Freudian theory set in stone. There is a long process, starting with the man himself and continuing after his death, of modification, revision and development of his thought.

As for Freud himself, the best introduction, I think, is to read him yourself. He is clear and more interesting than many of the introductions. My favourite remains his Introductory Lectures [6]. He’s also often his best critic. Like many genuinely creative and honest thinkers he questioned and challenged his own ideas as he went on. The result is, whatever the textbooks may tell you to the contrary, that there is no single Freudian theory set in stone. There is a long process, starting with the man himself and continuing after his death, of modification, revision and development of his thought.

A good example of Freud questioning himself is in his essay Beyond the Pleasure Principle (1920) where he seems to be thinking aloud, questioning his own theory and asking whether he has in fact been giving an inadequate account of the ‘pleasure principle’. These are not the writings of a guru incapable of self criticism. And for a man born in 1856, with all the tastes and views we’d associate with the period of his education and early development he can be remarkably ahead of the prejudices of his day. Consider the letter he sent in 1935 to a mother concerned that her son was homosexual and wanting ‘a cure’:

Homosexuality is assuredly no advantage, but it is nothing to be ashamed of, no vice, no degradation, it cannot be classified as an illness; we consider it to be a variation of the sexual function produced by a certain arrest of sexual development. Many highly respectable individuals of ancient and modern times have been homosexuals, several of the greatest men among them (Plato, Michelangelo, Leonardo da Vinci, etc.) It is a great injustice to persecute homosexuality as a crime and cruelty too.

Since his time a large number of theorists and practitioners have pushed his ideas in many directions: Donald Winnicott, Melanie Klein, Jacques Lacan, Mari Ruti, Alenka Zupančič, Slavoj Žižek Todd McGowan, Bruce Fink and many more.

Unscientific?

Unscientific?

But surely, he is ‘unscientific’? The problem here seems to be the idea that one cannot establish the causal claims of psychoanalysis. And this is true, if one is trying to use the methods of empirical sciences. No causal account in psychology can be established in that way, because here we are dealing with people and their meanings – with subjectivity. In daily life we interpret what the meanings are, challenge the accounts given and sometimes suspect that the person giving the account isn’t fully aware of her own motives. The same is broadly true of any interpretive discipline: think of history, for instance. When we work in these areas we try to gather more interpretive material and try to examine alternatives to the interpretation we favour. If we can’t do that because it is ‘unscientific’ we are going to have to give up a lot that cannot be assessed in the same way as physics: the causes of the First World War, the troubles in Ukraine, the origins of the Renaissance etc.

No account of this kind is immune to sceptical challenge, but that doesn’t make us give up on the project of understanding. History, economics and our normal ways of interpreting people lie outside of a frame work of understanding that could be simply falsified as one might with a theory in physics.[7] It’s a sign of psychoanalysis’ success that it doesn’t rely on such methods. And as Lear remarks, if people everywhere and always acted in rational ways transparent to themselves and others, and didn’t act in ways mysterious to themselves that cause them and others pain, that would falsify psychoanalysis. But perhaps the real object of the assault on Freud is that people are unhappy with the idea of there being an unconscious at all. If so, then some reflection on that lack of comfort ought to be in order. Meanwhile, Freud and psychoanalysis marches on – undead, despite the demise in 1939:

No account of this kind is immune to sceptical challenge, but that doesn’t make us give up on the project of understanding. History, economics and our normal ways of interpreting people lie outside of a frame work of understanding that could be simply falsified as one might with a theory in physics.[7] It’s a sign of psychoanalysis’ success that it doesn’t rely on such methods. And as Lear remarks, if people everywhere and always acted in rational ways transparent to themselves and others, and didn’t act in ways mysterious to themselves that cause them and others pain, that would falsify psychoanalysis. But perhaps the real object of the assault on Freud is that people are unhappy with the idea of there being an unconscious at all. If so, then some reflection on that lack of comfort ought to be in order. Meanwhile, Freud and psychoanalysis marches on – undead, despite the demise in 1939:

For about him till the very end were still

those he had studied, the fauna of the night,

and shades that still waited to enter

the bright circle of his recognition

turned elsewhere with their disappointment as he

was taken away from his life interest

to go back to the earth in London,

an important Jew who died in exile.

[8]

[1] Jonathan lear: ‘On Killing Freud (Again)’; New Republic, December 25, 1995, republished in Open Minded, Harvard University Press, 1998. I rely on this essay a good deal here.

[2] ibid., p 19.

[3] ‘The Effects of Cognitive Behavioral Therapy as an Anti-Depressive Treatment is Falling’: A Meta-Analysis Tom J. Johnsen and Oddgeir Friborg, (2015.) Psychological Bulletin, American Psychological Association:

https://uit.no/Content/418448/The effect of CBT is falling.pd

[4] Are Psychiatric Medications Making Us Sicker? John Horgan Scientific American, March 5th 2012, a review of Anatomy of an Epidemic: Magic Bullets, Psychiatric Drugs, and the Astonishing Rise of Mental Illness in America (Crown 2010), by Robert Whitaker

https://blogs.scientificamerican.com/cross-check/are-psychiatric-medications-making-us-sicker/

[5] Richard Boothby: Freud as Philosopher, Routledge, 2001, p 1.

[6] Sigmund Freud: The Penguin Freud Library, Vol.1: Introductory Lectures On Psychoanalysis.

[7] Actually, there is a good deal of theory in physics that eludes any simple attempts at replication and falsification – much of it around the nature of very small particles/waves.

[8] From WH Auden: ‘In Memory of Sigmund Freud’ https://poets.org/poem/memory-sigmund-freud