by Mary Hrovat

Mission to Earth: Landsat Views the World, Nicholas M. Short, Paul D. Lowman, Jr., Stanley C. Freden, William A. Finch, Jr. (published 1976)

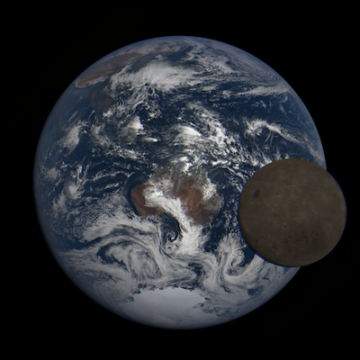

I found this book in a library at Indiana University when I was a student in the mid-1980s. I spent hours fascinated by the beauty of the photographs and the quiet, precise poetry of the geographical and geological terminology in the accompanying text.

Satellite images were not as readily available back then, and this book provides a rich banquet of them. Maps in the front of the book show where to find images of each part of the planet. First I looked up places I knew or had visited, and then I looked up places I wanted to visit or was curious about, and finally I just browsed. I’d always been interested in maps, with their place names and the history behind them. This book expanded that experience by giving me the geological, ecological, and human context of each image. It was endlessly interesting.

The book also expanded my horizons in another way. I had no theological qualms about the age of Earth or the universe, but I’d been shown a narrow world, growing up—a world centered on sin and redemption, where Earth is ultimately a way station between two eternities. I’d been a homebody as a child, caught up in my parents’ religious scruples and anxiously examining my behavior for not only sinful tendencies but also insufficient devotion to the divine.

This book was one of the things that released me to a wider view of life; it nurtured an enchantment with Earth, its dynamic intricacy and complex history, its reality as a thing in itself rather than a divine stage set. It absorbed me in the features and processes of the living planet. I didn’t realize it at the time, but I can see now that it sowed the seeds of a view of Earth itself as sublime and holy, in a completely natural sense. Read more »

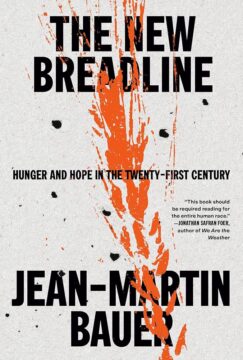

Many decades ago, I was fortunate to have had the opportunity of living in India for several years. I was enthralled by that country: its cultural richness; the environment; the food, but most of all the friendliness and warm hospitality of its diverse people. There were, of course, issues that confounded me and stark contradictions stared back at me from many directions, but of particular concern was the scale of the poverty amongst vast sections of the population, an issue that visited me at home frequently. A small begging community gathered regularly at my front gate, hungry and calling out for food. As my knowledge of the Indian social structure deepened, I came to understand that these people belonged to the most oppressed castes in Indian society and not only they, but a multitude of others were living in poverty, and with hunger.

Many decades ago, I was fortunate to have had the opportunity of living in India for several years. I was enthralled by that country: its cultural richness; the environment; the food, but most of all the friendliness and warm hospitality of its diverse people. There were, of course, issues that confounded me and stark contradictions stared back at me from many directions, but of particular concern was the scale of the poverty amongst vast sections of the population, an issue that visited me at home frequently. A small begging community gathered regularly at my front gate, hungry and calling out for food. As my knowledge of the Indian social structure deepened, I came to understand that these people belonged to the most oppressed castes in Indian society and not only they, but a multitude of others were living in poverty, and with hunger.

Chakaia Booker. Romantic Repulsive, 2019.

Chakaia Booker. Romantic Repulsive, 2019. I will use this column to defend myself against the accusation, first made by my surgical assistant Mr. Alan Turing, that I was negligent in the death of an individual under my medical care. Or, as one armchair prosecutor has said, that I am “a stereotypically British sentimentalist who thinks dogs are more human than people.”

I will use this column to defend myself against the accusation, first made by my surgical assistant Mr. Alan Turing, that I was negligent in the death of an individual under my medical care. Or, as one armchair prosecutor has said, that I am “a stereotypically British sentimentalist who thinks dogs are more human than people.”  There is a beautiful garden in a quiet tree-lined street in Manhattan’s Little Italy. There are rows of flower, lush, abundant and slightly wild, a stone balcony you can imagine Romeo climbing up to, stone balustrades, several lions, one with climbing vines adorning his face, a sphynx, various other statues, a copy of a Hermes medallion from the late antiquity, a fig tree and a hydrangea tree, giant shady pear trees, and many small hidden paths that lead to gazebos and intimate garden spaces. People in the garden sit and while the time or read by a little table. In a very small space, Elizabeth Street Garden has been able to replicate the richness of life, spaciousness of spirit, the magnanimity and dedication to beauty of the best Italian gardens. It is one of the truly great places in NYC. But after 12 years of struggle between the city and garden advocates, on June 18, 2024, the

There is a beautiful garden in a quiet tree-lined street in Manhattan’s Little Italy. There are rows of flower, lush, abundant and slightly wild, a stone balcony you can imagine Romeo climbing up to, stone balustrades, several lions, one with climbing vines adorning his face, a sphynx, various other statues, a copy of a Hermes medallion from the late antiquity, a fig tree and a hydrangea tree, giant shady pear trees, and many small hidden paths that lead to gazebos and intimate garden spaces. People in the garden sit and while the time or read by a little table. In a very small space, Elizabeth Street Garden has been able to replicate the richness of life, spaciousness of spirit, the magnanimity and dedication to beauty of the best Italian gardens. It is one of the truly great places in NYC. But after 12 years of struggle between the city and garden advocates, on June 18, 2024, the

e Mezzanine by Nicholson Baker is a novel about paying attention. After you read a chapter, you, too, begin paying attention to things you’ve never noticed before.

e Mezzanine by Nicholson Baker is a novel about paying attention. After you read a chapter, you, too, begin paying attention to things you’ve never noticed before.