by Richard Farr

The tree was immense even by local standards: a western red cedar that might have been a thousand years old. A botanist would want to measure it; I only wanted to touch its wrinkled face, or kneel among the roots and capture a dramatic snapshot looking up along the trunk. But it was fifty paces away and I couldn’t get there.

The tree was immense even by local standards: a western red cedar that might have been a thousand years old. A botanist would want to measure it; I only wanted to touch its wrinkled face, or kneel among the roots and capture a dramatic snapshot looking up along the trunk. But it was fifty paces away and I couldn’t get there.

We were 300 miles northwest of Vancouver, as the raven flies, on one of the countless islands of the Great Bear Rainforest. The Great Bear covers 25,000 square miles of British Columbia’s Central Coast, which makes it about the size of Sri Lanka. You can get into it by road, sort of, if you take a long, long detour around the back of the coastal mountains to the Bella Coola valley. But water has always been the real road in this maze of islands and inlets, so instead we drove our kayaks to Port Hardy, on the northern tip of Vancouver Island, rolled them onto the ferry, and rolled them off five hours later at the geographical and spiritual heart of British Columbia’s Central Coast, the Heiltsuk community of Bella Bella.

We paddled for twelve days. From the water we saw cormorants and sea otters beyond counting; porpoises; humpbacks. But the land seemed eerily empty, aside from a mink the color of salted chocolate that scampered past my feet one evening. Clawed prints in the sand. A few distant howls in the night. But the bears and wolves, and no doubt many other creatures, were perfectly hidden by the most dominant form of life, tens of millions of trees.

They cover almost everything. On most of the islands, whether fifty square miles or the size of a room, the forest approaches the water like a shoulder-to-shoulder army marching over a cliff, the edge marked by a constant slow-motion falling. The only shore is a yellowish ring of hand-shredding, barnacle-encrusted boulders, fortifications so uniform that it can be hard to finding even the sketchiest place to land. Camping is possible only because some islands have pockets of white sand beach.

Here, for me anyway, was a strange and arresting new experience of wilderness. Read more »

Julya Hajnoczky. Boletinellus Merulioides

Julya Hajnoczky. Boletinellus Merulioides Maybe it’s defeat in a short, sharp war far from home. Maybe Russia captures Ukraine, or China attacks Taiwan. Maybe nothing happens yet, maybe it’s four or eight years away, but however the big change comes we’ll all agree the signs were there all along.

Maybe it’s defeat in a short, sharp war far from home. Maybe Russia captures Ukraine, or China attacks Taiwan. Maybe nothing happens yet, maybe it’s four or eight years away, but however the big change comes we’ll all agree the signs were there all along.

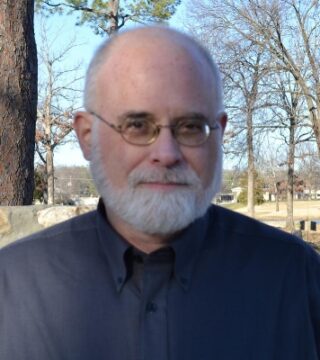

For over twenty years I have been in awe of David Jauss as a writer, as a colleague and teacher, and above all for his insight into the contradictory human heart. His short stories have been gathered together in two essential collections,

For over twenty years I have been in awe of David Jauss as a writer, as a colleague and teacher, and above all for his insight into the contradictory human heart. His short stories have been gathered together in two essential collections,

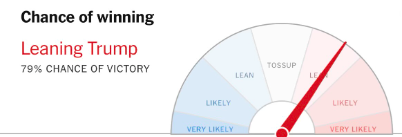

On November 5, 2024, at around 10:30 pm, I walked into a bar, approached the counter, and sat down on the stool second from the right. I ordered a stout because there was a slight chill in the air. As this was the night of the American presidential election, I pulled out my phone and checked The New York Times website, which said Donald Trump had an 80% chance of winning. This was my first update on the election, and it seemed bad. I put my phone back in my pocket and took a sip of the stout. A man entered the bar and sat down next to me, on my right. There was a half-drunk glass there, and I realized he’d gone out to smoke but had probably been at the bar for a while. Besides us—two solitary men at the bar—the rest of the place was busy, full of couples and groups who seemed to be unconcerned with the election. This may have been because I was in Canada, but my experience of living in Canada for the past four years has shown me that Canadians are just as interested in American politics as Americans are, if not more so. My work colleagues had been informing me of the key swing states, for example, while I had simply mailed in my meaningless Vermont vote and returned to my life. I had no idea who would win this election.

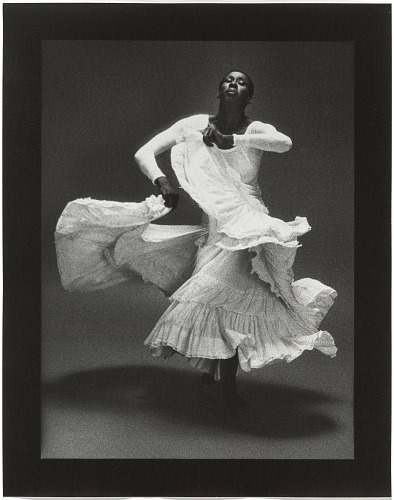

On November 5, 2024, at around 10:30 pm, I walked into a bar, approached the counter, and sat down on the stool second from the right. I ordered a stout because there was a slight chill in the air. As this was the night of the American presidential election, I pulled out my phone and checked The New York Times website, which said Donald Trump had an 80% chance of winning. This was my first update on the election, and it seemed bad. I put my phone back in my pocket and took a sip of the stout. A man entered the bar and sat down next to me, on my right. There was a half-drunk glass there, and I realized he’d gone out to smoke but had probably been at the bar for a while. Besides us—two solitary men at the bar—the rest of the place was busy, full of couples and groups who seemed to be unconcerned with the election. This may have been because I was in Canada, but my experience of living in Canada for the past four years has shown me that Canadians are just as interested in American politics as Americans are, if not more so. My work colleagues had been informing me of the key swing states, for example, while I had simply mailed in my meaningless Vermont vote and returned to my life. I had no idea who would win this election. Max Waldman. Judith Jamison in “Cry”, 1976.

Max Waldman. Judith Jamison in “Cry”, 1976.