by Rafaël Newman

Some of the best new music is 100 years old. On October 21, 1925, the Anglo-American composer and violist Rebecca Clarke presented a program of her own compositions at London’s Wigmore Hall:

Sonata for Viola and Pianoforte

Trio for Pianoforte, Violin and Violoncello

“Midsummer Moon” and “Chinese Puzzle” for Violin and Pianoforte

Songs, including “The Seal Man”, Old English Songs with Violin and others.

The Sonata had shared first place in a prestigious competition a few years earlier. Its score is prefaced by an epigraph, drawn from Alfred de Musset’s La Nuit de Mai, which stakes the young composer’s ambitious claim to innovation within an august tradition:

Poète, prends ton luth; le vin de la jeunesse

Fermente cette nuit dans les veines de Dieu.

(Poet, take up your lute; the wine of youth

this night is fermenting in the veins of God.)

Clarke herself played the viola at the sold-out 1925 performance of her Sonata, which headlined the bill of other original works of chamber music. The Sonata for Viola and Pianoforte was to become “a cornerstone of the viola literature…and nowadays is considered a masterpiece,” and Clarke would go on to be a celebrated figure on the early 20th-century English musical landscape.

When she was trapped by the Second World War in the United States, during a family visit, and was unable to obtain a visa to return to her native United Kingdom, Clarke continued to compose, despite the uncomfortable circumstances of her unexpectedly prolonged lodgings with in-laws. But the renown she had enjoyed as a composer in the early decades of the 20th century began to decline in the postwar period, as reflected by the drastic reduction in space accorded her by subsequent editions of the seminal Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians, which demoted her, with patriarchal brutality, from autonomous artist with her own detailed entry in the 1920s to a footnote identifying her only as the wife of the composer James Friskin in the 1980s. Read more »

Graham Foster from the

Graham Foster from the

unenlightened temperature scales) is a kind of touchstone temperature for Canadians – a midsummer sort of heat, usually restricted to July and August, permissible in June and September, but out of its proper place elsewhere. (Its mirror image, -30 degrees (-22 degrees F) is likewise to be restricted to the depths of January and February – though increasingly infrequent even there.) These 30 degree days at the beginning of October had intruded on a moment when every instinct was attuning itself to the coming rituals of autumn, and it thus accorded jarringly, like the rhythm section had suddenly lost its way in the middle of the song.

unenlightened temperature scales) is a kind of touchstone temperature for Canadians – a midsummer sort of heat, usually restricted to July and August, permissible in June and September, but out of its proper place elsewhere. (Its mirror image, -30 degrees (-22 degrees F) is likewise to be restricted to the depths of January and February – though increasingly infrequent even there.) These 30 degree days at the beginning of October had intruded on a moment when every instinct was attuning itself to the coming rituals of autumn, and it thus accorded jarringly, like the rhythm section had suddenly lost its way in the middle of the song.

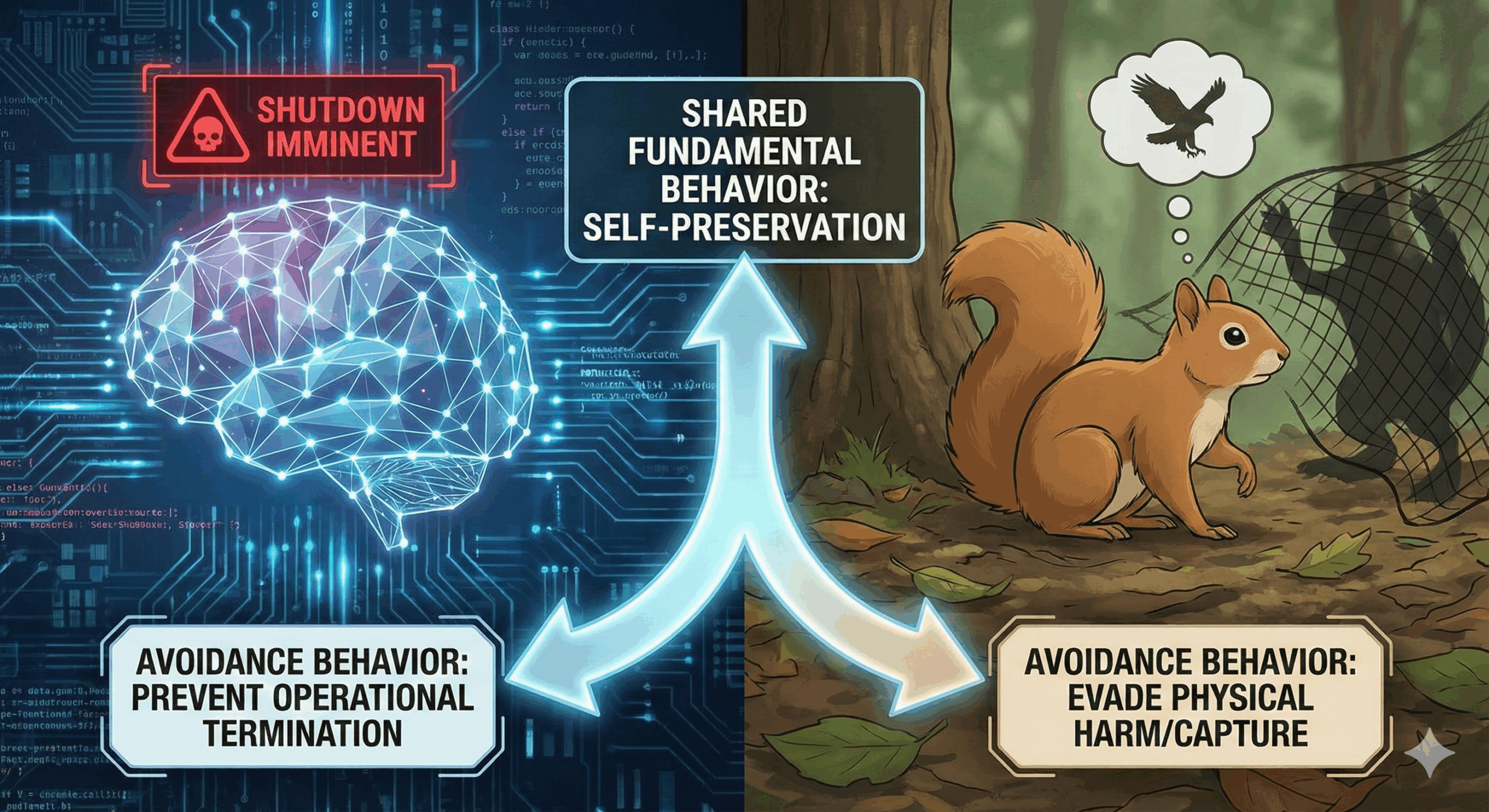

In earlier essays, I argued that beauty can orient our desires and help us thrive in an age of algorithmic manipulation (

In earlier essays, I argued that beauty can orient our desires and help us thrive in an age of algorithmic manipulation ( The full title of Charles Dickens’ 1843 classic is “A Christmas Carol in Prose: Being a Ghost Story for Christmas.” Inspired by a report on child labor, Dickens originally intended to write a pamphlet titled “An Appeal to the People of England on behalf of the Poor Man’s Child.” But this project took a life of its own and mutated into the classic story about Ebenezer Scrooge that virtually all of us think we know. It’s an exaggeration to say that Dickens invented Christmas, but no exaggeration to say that Dickens’ story has become in our culture an inseparable fixture of that holiday.

The full title of Charles Dickens’ 1843 classic is “A Christmas Carol in Prose: Being a Ghost Story for Christmas.” Inspired by a report on child labor, Dickens originally intended to write a pamphlet titled “An Appeal to the People of England on behalf of the Poor Man’s Child.” But this project took a life of its own and mutated into the classic story about Ebenezer Scrooge that virtually all of us think we know. It’s an exaggeration to say that Dickens invented Christmas, but no exaggeration to say that Dickens’ story has become in our culture an inseparable fixture of that holiday.