by Claire Chambers

Graham Foster from the International Anthony Burgess Foundation recently invited me to read and talk about R. K. Narayan’s The Vendor of Sweets (1967) for the Foundation’s podcast series. You can listen to our podcast here. The series is based on Burgess’s 1984 book Ninety-Nine Novels, in which the author of A Clockwork Orange selected his favourite novels of the twentieth century. The podcasts showcase a different Burgess preference for each show. Enjoying my rereading of Narayan and finding Graham’s questions stimulating, I decided to develop some of my answers for this blog post.

Graham Foster from the International Anthony Burgess Foundation recently invited me to read and talk about R. K. Narayan’s The Vendor of Sweets (1967) for the Foundation’s podcast series. You can listen to our podcast here. The series is based on Burgess’s 1984 book Ninety-Nine Novels, in which the author of A Clockwork Orange selected his favourite novels of the twentieth century. The podcasts showcase a different Burgess preference for each show. Enjoying my rereading of Narayan and finding Graham’s questions stimulating, I decided to develop some of my answers for this blog post.

On the surface, The Vendor of Sweets appears to be an unadorned novella about the life and family relationships of a widowed mithai seller. It also turns out to be a comic meditation on the encounters and clashes of so-called tradition and modernity in India. The novel’s tight plotting revolves around Jagan, a man whose life as a sweet vendor sits uneasily with his past anticolonial activism and present devout Hinduism. When Jagan’s ‘foreign-returned’ only son, Mali, brings home a Korean-American partner and an ambition to start up a business manufacturing story-writing machines, Jagan finds himself sidelined and unmoored.

I first read The Vendor of Sweets during my MA at the University of Leeds. Along with another of Narayan’s novels, The Guide, it made a lasting impression. I appreciated the author’s concise prose and accessible and funny storytelling. More than that, his insights into the cultural transformations occurring in post-partition India left me entertained and educated.

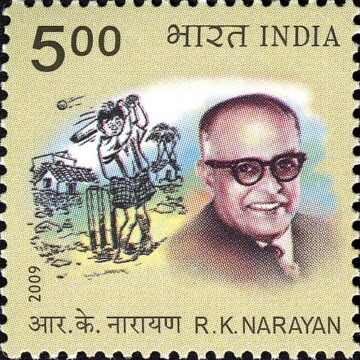

Narayan’s journey to publication adds texture to understandings of his work. His relationship with Graham Greene helped introduce the Indian novelist’s works to a broader, international audience. However, as with other such pairings – springing to mind are W. B. Yeats’s complex relationship with Rabindranath Tagore, and Virginia and Leonard Woolf’s publication of Mulk Raj Anand in the Hogarth Press – there were (neo)colonialist overtones to this. No wonder such activities are known as ‘patronage’, since they can be patronizing and unequal. A white British writer like Greene being a ‘patron’ to a racialized writer, especially given the Narayan’s position as a colonial subject (at the time Greene began corresponding with him) leaves the postcolonial critic feeling uncomfortable or even enraged. By contrast, the way Burgess framed Narayan in Ninety-Nine Novels is brief and still slightly condescending, but he does showcase the way the Indian novelist wrote ‘consistently well’ and created a storyworld that is ‘beautifully caught’. Indeed, Narayan was nobody’s victim, since he handled his relationships with Western writers graciously but then carved out his own writerly path.

A significant element across Narayan’s works is his creation of Malgudi, a fictional town that is the setting for most of his novels. Malgudi is located somewhere in south India and functions as a microcosm of the country. By situating his narratives in this imagined place, Narayan liberates himself from the confines of any one region’s peculiarities, instead presenting an India that to an extent exists outside time and space. This is not done in a showy or metafictional way, as with Salman Rushdie’s mobilization in Midnight’s Children (1981) of Saleem Sinai and his Methwold Estate location in Bombay/Mumbai as emblems of the pre- and post-partition nation-state. Instead, Narayan is focused on world-building, whereby Malgudi’s geographical and psychosocial locations are imagined with precision.

A significant element across Narayan’s works is his creation of Malgudi, a fictional town that is the setting for most of his novels. Malgudi is located somewhere in south India and functions as a microcosm of the country. By situating his narratives in this imagined place, Narayan liberates himself from the confines of any one region’s peculiarities, instead presenting an India that to an extent exists outside time and space. This is not done in a showy or metafictional way, as with Salman Rushdie’s mobilization in Midnight’s Children (1981) of Saleem Sinai and his Methwold Estate location in Bombay/Mumbai as emblems of the pre- and post-partition nation-state. Instead, Narayan is focused on world-building, whereby Malgudi’s geographical and psychosocial locations are imagined with precision.

The Vendor of Sweets explores a standoff between Indian and Western, specifically American, values. Narayan does not offer a simplistic, black-and-white portrayal of modernization. Instead, he gives us both earth and jewel tones, showing that modernity in India presents opportunities and dilemmas. Modernity may promise progress and material prosperity, especially to women and/or those oppressed by caste structures. However, to many people, including Jagan, it also carries the risk of ruthless capitalist extractivism and a dilution of India’s rich cultural heritage.

Jagan is horrified by Mali’s newfound materialism when the prodigal son returns from the US. In retaliation, the patriarch tries to bend his own profession back to the communal and nurturing traditions of Indian society that he thinks were lost when the nationalist struggle was won and there was no longer such an urgent need for Gandhism. Defiant Jagan starts to sell sweetmeats at cost price rather than for profit, in the process receiving opprobrium and exploitation from his rival vendors and scorn from his son.

This renunciate attitude stands in direct opposition to a modern sensibility. In a way the novel dramatizes Jagan’s transition away from the Grihastha or householder period in the Hindu four-stage life system. Such stages are known in the novel as a Janma (birth/life), and elsewhere as an Ashrama. Grihastha is a phase dedicated to family, work, and social responsibilities. But Jagan now moves towards the Vanaprastha Ashrama when one gradually withdraws from worldly duties.

As noted, it is Mali who prompts Jagan’s retirement from the material world. Eager to make his way in business and procure a better life, Mali’s decision to travel to the US makes sense but his choice to study Creative Writing is surprising. Mali’s journey at first seems to represent a search for identity beyond commerce, intermixing entrepreneurship with creativity. Here Narayan highlights India’s balance between economic ambition and intellectual curiosity.

Yet, as is usually the case in Narayan’s writing, there is more to it than that. Revisiting the novel for this blog post, more than twenty years since my original perusal, was instructive. Amid present anxieties around ChatGPT and the possibility that artificial intelligence is leading to the replacement of artists and their labour, or may eventually bring about human extinction, the story-writing machine strand of Narayan’s novel takes on new significance. Writing of The Vendor of Sweets, Anthony Burgess said that the story-writing machine contained ‘shades of Nineteen Eighty-Four’ (another of his ninety-nine favourites). In George Orwell’s novel, the protagonist Winston’s love interest Julia works in the Fiction Department where Oceania’s authoritarian ruling Party uses machines to churn out literature, music, and entertainment tailored to manipulate and pacify the masses. There, art is stripped of individuality and meaning, and the non-literary Julia ‘swap[s] around’ plots generated automatically. Shades of 2025?

Yet, as is usually the case in Narayan’s writing, there is more to it than that. Revisiting the novel for this blog post, more than twenty years since my original perusal, was instructive. Amid present anxieties around ChatGPT and the possibility that artificial intelligence is leading to the replacement of artists and their labour, or may eventually bring about human extinction, the story-writing machine strand of Narayan’s novel takes on new significance. Writing of The Vendor of Sweets, Anthony Burgess said that the story-writing machine contained ‘shades of Nineteen Eighty-Four’ (another of his ninety-nine favourites). In George Orwell’s novel, the protagonist Winston’s love interest Julia works in the Fiction Department where Oceania’s authoritarian ruling Party uses machines to churn out literature, music, and entertainment tailored to manipulate and pacify the masses. There, art is stripped of individuality and meaning, and the non-literary Julia ‘swap[s] around’ plots generated automatically. Shades of 2025?

What is distinctive about Narayan’s approach is, first, its postcolonial dimension and, second, its early time of production in the 1960s. A lot of postcolonial literature engages with who controls the story, which makes it easy to extend into AI-generated narratives. If an AI is writing stories, who trained it? Which histories and perspectives does it reinforce, erase, or scrape? Mali contends that India must enhance its literary production to rival ‘advanced cultures’ like America’s, necessitating the use of story-writing machines. But Jagan resists Mali’s embrace of the story-writing machine with his idea that India’s storytelling is undergirded by millennia of tradition via tales from the Mahabharata and Ramayana. Narayan juxtaposes the machine with Jagan’s evocation of a timeless ‘village granny’ storyteller, thus humanizing, gendering, and ageing the telling of tales.

Adding further feminist and inter-ethnic angles to this narrative of transformation is the character of Mali’s wife. Grace’s very specific identity as a Korean-American woman gives the text a sense of the cultural confluence caused by globalization. Her presence in the novel reminds of the permeability of communal boundaries. Jagan originally finds her horrifyingly modern and exotic, with her short hair and confidence within and outside the home. However, she ultimately contributes to the dialogue on cultural hybridity. Choosing to wear a sari and serving her father-in-law with love despite her independent outlook, Grace is a figure who suggests that modern India is not isolated but has strong connections both to North America and Asia.

Adding further feminist and inter-ethnic angles to this narrative of transformation is the character of Mali’s wife. Grace’s very specific identity as a Korean-American woman gives the text a sense of the cultural confluence caused by globalization. Her presence in the novel reminds of the permeability of communal boundaries. Jagan originally finds her horrifyingly modern and exotic, with her short hair and confidence within and outside the home. However, she ultimately contributes to the dialogue on cultural hybridity. Choosing to wear a sari and serving her father-in-law with love despite her independent outlook, Grace is a figure who suggests that modern India is not isolated but has strong connections both to North America and Asia.

Despite being written nearly sixty years ago, The Vendor of Sweets still has a lot to say. Its themes of cultural collision, the search for identity, and the tension between tradition and modernity remain as pertinent now as they were at the time of its publication. Readers in the twenty-first century can interpret its narrative as a nostalgic reflection on a bygone era and a prescient warning about the potential costs of cultural assimilation and rapid technological advancements. Returning to The Vendor of Sweets in a digital duniya (world) suggests that the future of narrative must not be shaped by algorithms or patronising gatekeepers but by the embodied labour of consummate storytellers like Narayan.

***

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.