by Jonathan Kujawa

That led me to triangles. If one of the first counting numbers could be so interesting, then surely the first nontrivial polygon must be worth a second or third look? After all, Ben Orlin has a top ten list of his favorite triangles. On the other hand, what more can be said? After all, people have thought about the mathematics of triangles for thousands of years. The Babylonians knew about triangular mathematics and the square root of two in 1600 BCE.

Probably the most famous theorem about triangles is the Pythagorean Theorem. If you stop someone on the street and ask them what they know about triangles, no doubt the Pythagorean Theorem is going to be very high on their list. It even makes an appearance of sorts in the Wizard of Oz [1].

The Pythagorean Theorem is certainly handy, including in real-world geometric calculations. And it has a simple elegance that is hard to beat. Lewis Caroll wrote in 1895: “It is as dazzlingly beautiful now as it was in the day when Pythagoras first discovered it.” Part of what makes it so famous, though, is its many, many, many, many, many proofs. For example, here is a wordless proof from Wikipedia:

Why bother? After all, more proofs don’t make the Pythagorean Theorem more true. Partially, it is just for the fun of it. Rather than doomscrolling on TikTok, why not noodle on Pythagorean’s Theorem or another bit of geometry? Perhaps a better reason is that a new proof requires new thinking, and new thinking can give new understanding. In writing this essay, I learned about Barry Mazur’s Pythagorean Blob Theorem. Not only is it a cool way to think about the Pythagorean Theorem, it illustrates Polya’s inventor’s paradox: sometimes it is easier to solve a seemingly more general and harder problem. Here is a charming ten-minute video about it.

Of course, right triangles aren’t the only triangles. What about all the wrong triangles? Apocryphally, Napoleon Bonaparte supposedly came up with what we now call Napoleon’s Theorem. It says that if you start with a triangle, put an equilateral triangle on each side of that original triangle, then the centers of those equilateral triangles form an equilateral triangle.

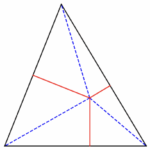

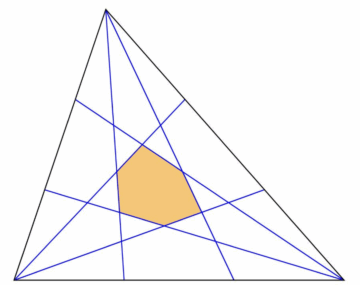

In another personal connection, I recently learned of Marion’s Theorem. It was discovered by Marion Walters, who was emeritus faculty at the University of Oregon when I was a graduate student. I remember Marion with great fondness as a kind person you could easily chat with at departmental teas. Little did I know that Marion and her collaborators discovered a remarkable result about triangles only a few years before those teas! Say you start with an arbitrary triangle and draw the pairs of lines for each angle that split that angle into three equal angles. The result will be a hexagon in the middle of the triangle formed by the six lines:

Marion’s theorem is that the area of the hexagon is always exactly 1/10 the area of the original triangle. Why 1/10? I have no idea. There is no obvious reason it should be true, nor that the number 10 should play a role. This feels like one of those theorems where you will need to read multiple proofs to get a feeling for where the 1/10 comes from.

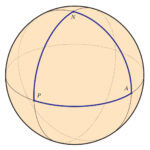

I shared Marion’s theorem with my colleague, Ren Guo. One of Ren’s research interests is to take a result from Euclidean geometry and find its analogues in non-Euclidean geometry. For example, we live on the sphere known as the Earth. You can draw triangles and other geometric shapes on the surface of a sphere and ask what happens in this new geometry. You have to be careful. Your geometric intuition can fail you. For example, a triangle with one vertex at the north pole and two on the equator can have three right angles!

I shared Marion’s theorem with my colleague, Ren Guo. One of Ren’s research interests is to take a result from Euclidean geometry and find its analogues in non-Euclidean geometry. For example, we live on the sphere known as the Earth. You can draw triangles and other geometric shapes on the surface of a sphere and ask what happens in this new geometry. You have to be careful. Your geometric intuition can fail you. For example, a triangle with one vertex at the north pole and two on the equator can have three right angles!

Nevertheless, if you’re careful, you can often still translate classical geometric facts into non-Euclidean geometry. For example, if your sphere has radius R, and you have a right triangle ABC where the right angle is C, then the spherical version of the Pythagorean Theorem is

![]()

While it is a nice-looking formula, it doesn’t look much like the Pythagorean Theorem, does it? It is actually hidden in this formula. First, you write the cosines using Taylor series from calculus. You then study what happens as the radius R gets larger and larger. The larger the radius, the bigger the sphere, and the flatter its surface becomes (the bigness of the Earth is why Oklahoma looks so flat when you look across the plains). As R tends towards infinity, the Taylor series of this formula tends toward the classic Pythagorean Theorem that you know and love.

Ren indulged me by spending a day trying to figure out a spherical or hyperbolic version of Marion’s theorem. He didn’t have any luck, though. That means, as far as I know, it is an open question to find a version of Marion’s theorem in non-Euclidean geometry. If high school students can find new proofs of the Pythagorean Theorem 2000+ years after Euclid, I can’t imagine we’re finished learning about triangles.

[1] Image borrowed from here.

[2] Speaking of learning new things, I just learned that the Scarecrow’s confidently incorrect version of the Pythagorean Theorem was a deliberate choice by the screenwriters. It was meant to show that the Wizard did not give the Scarecrow knowledge or intelligence, only confidence.

[3] Animation created by William B. Faulk – https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Pythagoras-proof-anim.svg, CC BY-SA 4.0, Link.

[4] Although even here, the Babylonians were ahead of the curve. The Plimpton 322 cuniform tablet shows that they were aware of what we now call Pythagorean Triples. These are a list of three counting numbers that can be used to make up the sides of a right triangle. For example, (3,4,5), (7, 24, 25), and (20,99,101) are Pythagorean Triples.

[5] How far we have fallen. It is hard to imagine a US Congressman doing math recreationally these days, never mind actually contributing something new!

[6] Image borrowed from John Cook’s excellent micro-blog.

[7] In another curious coincidence, the Barrow who proved Erdos’s conjecture was David F. Barrow, a mathematician at the University of Georgia. I spent nearly four years at UGA and frequently walked by Barrow Elementary School on my way to work, named after Barrow’s father, another UGA mathematician.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.