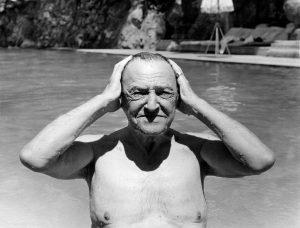

by Bill Murray

Hyvä asiakkaamme,

Ethän käytä huoneiston takkaa.

Se on tällä hetkellä epäkunnossa

Ja savuttaa sisään.

Dear customer,

Please don’t use the fireplace. It is for the moment out of order and the smoke comes into the apartment.

Now wait a minute. We might need that fireplace in Lapland in December. Just now it’s three degrees (-16C) outside. The nice lady couldn’t be more sympathetic, but they just manage the place. Fixing the fireplace requires funding that can’t be organized until we are gone.

She promises we’ll stay warm thanks to a magnificent heater, a sauna and the eteinen, one of those icebox-sized northern anterooms that separate the outside from the living area. I have fun with the translation, though. I imagine that fool Ethän has busted the damned fireplace again.

• • •

Welcome to Saariselkä, Finland, where it’s dark in the morning, briefly dusk, then dark again for the rest of the day. The sun never aspires to the horizon. Fifty miles up the road Finland, Norway and Russia meet at the top of Europe.

But look around. It’s entirely possible to live inside the Arctic Circle. It takes a little more bundling up and all, and you need a plan before you go outside. No idle standing around out there.

There are even advantages. Trailing your groceries after you on a sled, a pulkka, is easier than carrying them. There’s a word for the way you walk: köpöttää. It means taking tiny steps the way you do to keep your balance on an icy sidewalk.

Plus, other humans live here, too, and they seem to get along just fine. Infrastructure’s good, transport in big, heavy, late model SUVs, a community of 2600 people, all of them attractive, all of whom look just like each other.

I imagined “selling time shares in Lapland” was a punch line, but it’s an actual thing. A jammed-full Airbus delivered us from Helsinki, one of three flights every day to Rovaniemi. Read more »

I have been a practicing Stoic for a few years now, with lulls here and there. Stoicism provides a compelling framework for living in a purposeful and ethical way. The question in my mind is, is it perhaps a little too compelling? In other words, not much fun?

I have been a practicing Stoic for a few years now, with lulls here and there. Stoicism provides a compelling framework for living in a purposeful and ethical way. The question in my mind is, is it perhaps a little too compelling? In other words, not much fun?

In 1790, shortly after the 13 states ratified the U.S. Constitution, the new federal government conducted its first population census. Its tabulations revealed an astonishingly rural nation. No less than 95% of all Americans lived in rural areas, either on a fairly isolated homestead (typically a farm) or in a very small town. How small? Fewer than 2,500 people. Meanwhile, just 1/20 of Americans lived in a town with more than 2,500 people. All told there were only 26 such towns, only half of which had so many as 5,000 people

In 1790, shortly after the 13 states ratified the U.S. Constitution, the new federal government conducted its first population census. Its tabulations revealed an astonishingly rural nation. No less than 95% of all Americans lived in rural areas, either on a fairly isolated homestead (typically a farm) or in a very small town. How small? Fewer than 2,500 people. Meanwhile, just 1/20 of Americans lived in a town with more than 2,500 people. All told there were only 26 such towns, only half of which had so many as 5,000 people

Three years ago I posted on this site “

Three years ago I posted on this site “