by Samia Altaf

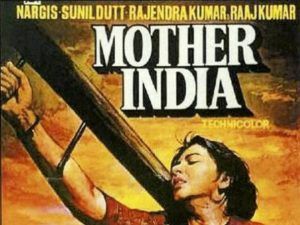

Actors come to each role in a new film bearing the stamp of their old ones so they are richer and more interesting in the new incarnation—the whole more than the sum of the parts. Just last week one saw Nargis as the innocent and naive mountain girl pining away for the love of the ‘shehri babu’, and today she is the femme fatale, all hell and brimstone, plotting the downfall of her rival. Or, as Mother India, upholding principles of honesty and justice, shooting her favorite son dead for raping a village girl.

Actors come to each role in a new film bearing the stamp of their old ones so they are richer and more interesting in the new incarnation—the whole more than the sum of the parts. Just last week one saw Nargis as the innocent and naive mountain girl pining away for the love of the ‘shehri babu’, and today she is the femme fatale, all hell and brimstone, plotting the downfall of her rival. Or, as Mother India, upholding principles of honesty and justice, shooting her favorite son dead for raping a village girl.

Most of the time the female protagonists in our local films were uneducated but good, pious women seemingly knowing little of the world’s evil. They existed in a limited space, physically and mentally circumscribed by a patriarchal society, sheltered and protected by ‘their’ men and dependent on them for validation. They could cook up a storm, look after the household, sweep and clean, tend to animals and sick husbands, all in a day, without getting tired or complaining.

But they remained submissive women who suffered silently and deferred endlessly to their husbands, fathers, brothers, sons, and society. What would people say? What would make the family lose face? The family ‘honor’ was always tied to a woman’s behavior, to her desires, and no one was allowed to forget that. Conforming to those norms secured women a place in the community, credibility and status, and the more they suffered and sacrificed themselves the more they were lauded as role models. Such lessons were not lost on young girls and boys and went a long way in shaping expectations for their futures and standards of acceptable behavior. Read more »

Donald Trump is not a fascist. He’s far too stupid to be a fascist, or to coherently advocate for any complex national political doctrine, evil or otherwise. He is, however, a would-be tin pot dictator. And his largely failed but still very dangerous attempts to establish himself as a right wing autocrat need to be countered, not just by opposition politicians and the press, but also by responsible citizens.

Donald Trump is not a fascist. He’s far too stupid to be a fascist, or to coherently advocate for any complex national political doctrine, evil or otherwise. He is, however, a would-be tin pot dictator. And his largely failed but still very dangerous attempts to establish himself as a right wing autocrat need to be countered, not just by opposition politicians and the press, but also by responsible citizens. This past Sunday, November 11, marked the Centennial of Armistice Day, the European commemoration of the agreement to end World War I. Representatives from more than 60 countries attended carefully choreographed ceremonies to honor the sacrifice of those who fought.

This past Sunday, November 11, marked the Centennial of Armistice Day, the European commemoration of the agreement to end World War I. Representatives from more than 60 countries attended carefully choreographed ceremonies to honor the sacrifice of those who fought.

In a recent study, data scientists based in Japan found that classical music over the past several centuries has followed laws of evolution. How can non-living cultural expression adhere to these rules?

In a recent study, data scientists based in Japan found that classical music over the past several centuries has followed laws of evolution. How can non-living cultural expression adhere to these rules?

The crocodiles know. They form pincers on either side of the crossing point. Richard says they feel the vibration of all those hooves along the riverbank above them.

The crocodiles know. They form pincers on either side of the crossing point. Richard says they feel the vibration of all those hooves along the riverbank above them.

By chance, I chose as holiday reading (awaiting my attention since student days) The Epic of Gilgamesh, a Penguin Classics bestseller, part of the great library of Ashur-bani-pal that was buried in the wreckage of Nineveh when that city was sacked by the Babylonians and their allies in 612 BCE. Gilgamesh is a surprisingly modern hero. As King, he accomplishes mighty deeds, including gaining access to the timber required for his building plans by overcoming the guardian of the forest. But this victory comes at a cost; his beloved friend Enkidu opens by hand the gate to the forest when he should have smashed his way in with his axe. This seemingly minor lapse, like Moses’ minor lapse in striking the rock when he should have spoken to it, proves fatal. Enkidu dies, and Gilgamesh, unable to accept this fact, sets out in search of the secret of immortality, only to learn that there is no such thing. He does bring back from his journey a youth-restoring herb, but at the last moment even this is stolen from him by a snake when he turns aside to bathe. In due course, he dies, mourned by his subjects and surrounded by a grieving family, but despite his many successes, what remains with us is his deep disappointment. He has not managed to accomplish what he set out to do.

By chance, I chose as holiday reading (awaiting my attention since student days) The Epic of Gilgamesh, a Penguin Classics bestseller, part of the great library of Ashur-bani-pal that was buried in the wreckage of Nineveh when that city was sacked by the Babylonians and their allies in 612 BCE. Gilgamesh is a surprisingly modern hero. As King, he accomplishes mighty deeds, including gaining access to the timber required for his building plans by overcoming the guardian of the forest. But this victory comes at a cost; his beloved friend Enkidu opens by hand the gate to the forest when he should have smashed his way in with his axe. This seemingly minor lapse, like Moses’ minor lapse in striking the rock when he should have spoken to it, proves fatal. Enkidu dies, and Gilgamesh, unable to accept this fact, sets out in search of the secret of immortality, only to learn that there is no such thing. He does bring back from his journey a youth-restoring herb, but at the last moment even this is stolen from him by a snake when he turns aside to bathe. In due course, he dies, mourned by his subjects and surrounded by a grieving family, but despite his many successes, what remains with us is his deep disappointment. He has not managed to accomplish what he set out to do. On his journey, Gilgamesh meets the one man who has achieved immortality, Utnapishtim, survivor of a flood remarkably similar, even in its details, to the Flood in the Bible. Reading of this sent me back to Genesis, and hence to two other books,

On his journey, Gilgamesh meets the one man who has achieved immortality, Utnapishtim, survivor of a flood remarkably similar, even in its details, to the Flood in the Bible. Reading of this sent me back to Genesis, and hence to two other books, Comparing Hebrew with Cuneiform may seem like a suitable gentlemanly occupation for students of ancient literature, but of no practical importance. On the contrary, I maintain that what emerges is of major contemporary relevance.

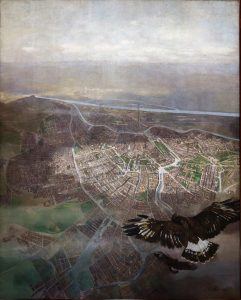

Comparing Hebrew with Cuneiform may seem like a suitable gentlemanly occupation for students of ancient literature, but of no practical importance. On the contrary, I maintain that what emerges is of major contemporary relevance. When architect Otto Wagner commissioned this large painting by Carl Moll for the Kaiser’s personal railroad station in Vienna in 1899, he might not have seen the irony of an eagle’s view of the city. View of Vienna from a Balloon envisions a future beyond rails in which a bird shows the way to a whole new way of looking at landscape, one that would renew the way we view nature itself, hardly more than a 100 years later. If that painting were done today, the eagle would be replaced by a small four-cornered device with a camera and four rotary blades to keep it aloft: the drone.

When architect Otto Wagner commissioned this large painting by Carl Moll for the Kaiser’s personal railroad station in Vienna in 1899, he might not have seen the irony of an eagle’s view of the city. View of Vienna from a Balloon envisions a future beyond rails in which a bird shows the way to a whole new way of looking at landscape, one that would renew the way we view nature itself, hardly more than a 100 years later. If that painting were done today, the eagle would be replaced by a small four-cornered device with a camera and four rotary blades to keep it aloft: the drone.