by Samia Altaf

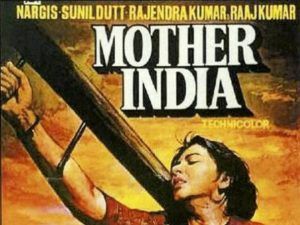

Actors come to each role in a new film bearing the stamp of their old ones so they are richer and more interesting in the new incarnation—the whole more than the sum of the parts. Just last week one saw Nargis as the innocent and naive mountain girl pining away for the love of the ‘shehri babu’, and today she is the femme fatale, all hell and brimstone, plotting the downfall of her rival. Or, as Mother India, upholding principles of honesty and justice, shooting her favorite son dead for raping a village girl.

Actors come to each role in a new film bearing the stamp of their old ones so they are richer and more interesting in the new incarnation—the whole more than the sum of the parts. Just last week one saw Nargis as the innocent and naive mountain girl pining away for the love of the ‘shehri babu’, and today she is the femme fatale, all hell and brimstone, plotting the downfall of her rival. Or, as Mother India, upholding principles of honesty and justice, shooting her favorite son dead for raping a village girl.

Most of the time the female protagonists in our local films were uneducated but good, pious women seemingly knowing little of the world’s evil. They existed in a limited space, physically and mentally circumscribed by a patriarchal society, sheltered and protected by ‘their’ men and dependent on them for validation. They could cook up a storm, look after the household, sweep and clean, tend to animals and sick husbands, all in a day, without getting tired or complaining.

But they remained submissive women who suffered silently and deferred endlessly to their husbands, fathers, brothers, sons, and society. What would people say? What would make the family lose face? The family ‘honor’ was always tied to a woman’s behavior, to her desires, and no one was allowed to forget that. Conforming to those norms secured women a place in the community, credibility and status, and the more they suffered and sacrificed themselves the more they were lauded as role models. Such lessons were not lost on young girls and boys and went a long way in shaping expectations for their futures and standards of acceptable behavior.

Professional or educated women were rarely seen in the pictures. If one did appear, it was in a side role: a nurse holding the hero’s head as he lay dying while professing undying love for his estranged wife; or a secretary in a large business-house, in the clutches of a lecherous co-worker or a more lecherous boss, waiting to be rescued by a knight in shining armor to be carried off to wifely bliss; or a nightclub dancer forced into the profession by circumstances—a consumptive father, a long-suffering mother or a brilliant younger brother desperately in need of schooling. Unhappy in her ‘job,’ she too was waiting to be rescued, to be assigned her true role of wife and mother, thereby leading everyone—the father, the mother, and the brother— to live happily ever after. How that would come about was never clear but clearly understood.

Rarely was a woman allowed to step out of the normative role to display personal agency and act to fulfill private desires which, of course, always got her into deep trouble and led to no good for all. She might be the warden of a girls’ hostel or a doctor perched behind an imposing desk, stiff-backed, head held high, wearing an elegant colorful outfit, looking quite content, speaking with authority, giving orders, and expecting to be obeyed. She’d care two hoots for romance or a rescue, refuse to be budged from her place, and deny the keys of daddy’s safe to her debauched, entitled brothers. But even then, the subtext was clear—these were dry, sterile, infertile women, foolish and misguided, who were acting thus only because motherhood and wifehood was denied them and they would soon meet their comeuppance. The characters usually repented in the end—the plot stayed true to society’s norms.

English films were different. They showed women who were smart and ambitious and manipulative, if necessary, in pursuit of personal goals all while being smartly dressed with hair in place. Doris Day was the shining star of that kind of womanhood—slim, statuesque, and blue-eyed which got her extra points in our colonial minds. In Pillow Talk she was an interior decorator who gave the womanizing hero played by Rock Hudson—the handsome heart throb of millions of women and men too—as good as she got. In The Man Who Knew Too Much she was a loving and supportive wife but still had a presence of her own. She fought, successfully, to get her husband out of the clutches of his new wife, in Move Over Darling. Then there was the sexy Gina Lollobrigida who manipulated the two leading men in Trapeze to clamber her way to the top.

Profoundly affected as I was by each picture I saw, there was one film that changed my life completely. That was Cleopatra starring Elizabeth Taylor in the role of the brave and beautiful queen. I saw the picture in the fancy Bambino Cinema in Karachi where we went by overnight train from Sialkot to spend the summer. Getting to screen Cleopatra was a coup for Bambino, showcasing its top-of-the-line stereoscopic sound system and 3D visuals. Poor Lalazar, despite its curvy marble staircase, could not dream of coming close. At the time Bambino was owned by Mr. Hakim Ali Zardari who later came to fame and much fortune when his son, Asif, married the young and beautiful Benazir Bhutto, the up-and-coming star in Pakistan’s political landscape. Benazir, the frail Oxford-educated David stood up to the Goliath of the military dictator Zia ul Haq who had ousted and hung her father, Zulfiqar. Benazir would go on to become Prime Minister at age 37, be elected to that office twice, and assassinated campaigning the third time leaving Asif Zardari, of dubious morals and cheesy grin, the most powerful and richest man in the country. But at the time Cleopatra was screened the Zardaris were regular folks who owned and ran a cinema that was among the best in the country—a far better thing than what they got into subsequently while letting Bambino go to seed.

It was there, in that heady summer of 1964, while the Beatles sang, “I wanna hold your hand,” a summer of self-discovery in many other ways as well—there was a dark-haired neighbor with an Elvis-like curl to his lip and we took to sitting under the guava tree in the somnolent afternoons to read Illustrated Classics, at least that was the intent—that I saw Elizabeth Taylor as the queen insouciantly wearing diaphanous gowns and wrapping all the high and mighty of Rome and Egypt around her little finger. Just the house-sized bill-board outside Bambino, showing Ms. Taylor’s marble thighs, as big as a tree-trunks, peeping through her gown, was enough to knock anyone senseless. Then one saw the Queen—in costume after costume, nifty sexy outfits each more spectacular than the last, kohl-lined eyes, exquisite jewels, and a bevy of slaves—seducing generals right and left while fighting wars and undertaking major policy decisions. Way to go! That was it! That was what the thing to do. How difficult could that be?

I loved the fact that when Cleopatra rolled out of the carpet she employed to sneak into Caesar’s room, she had her high-heeled sandals secure, her hair in place, and not even a carpet hair in her eye. And later, when Caesar comes visiting, she invites in the general half-clad in her house clothes. Instead of reaching for outer-wear or an extra covering as I was taught to do—spreading the dupatta to guard my breasts (non-existent at the time), the practice of good Muslim girls in presence of outsiders—Cleopatra takes off whatever little she is wearing exposing those legendry thighs in 3-D cinemascope glory, steps into the bath tub, and calmly talks foreign policy with the armor-plated General sitting on a stool bedside her. (By the time I saw the movie twenty years later, Rex Harrison had acquired fame as the acerbic Henry Higgins and I half expected Caesar to break into a frustrated “why can’t a woman be more like a man,” the song from My Fair Lady.)

It was quite understandable why Mark Antony would be so besotted by her though a pity for a general to be reduced to such a sorry state. He did not stand a chance before her seductive powers backed up by barges of solid gold and Egypt’s wealth. Awesome. I swear she sent me subliminal messages as I sat dumbstruck in that darkened hall.

That was who I was going to be when I grew up. I was going to wear exquisite clothes, get funky hair styles, seduce generals, fight wars, dismiss senators, party on ships of gold, have faithful slaves to massage and bathe me, their hearts full of unending and undying love. I did think though that getting her children killed and herself bitten by a snake was quite unnecessary. Surely, given her smarts, she could have found a way around that and not spoil the whole thing. But who was I to make heavy judgments from my small world. I cried bitter tears at her death for my ambition was real and true though I had no intention to be bitten by a snake. Part of the will still lingers somewhere refusing to be beaten down by an ordinary life lived ordinarily. I am glad I had the good sense not to tell my mother and grandmother about my ambitions.

What did the pictures do for me? Though at the time one did not know or seek them actively, the pictures conveyed lessons in history or, more accurately, the versions of history popular with the mainstream filmmakers; they gave lessons in politics and spelled out the cultural norms of acceptable behavior. On the one hand they shaped the landscape of our lives, and suggested, subliminally, how it ought to be populated. There were heroes and villains, brave men, self-sacrificing women, long-suffering wives, deferential sisters, authoritarian fathers, a system that was stacked against the honest and the good but in which truth triumphed in the end with hard work, honesty, grit, and the blessings of Allah. Yet, they also showed glimpses of other lives and visions of other possibilities where one could articulate desires and shape one’s own world and, in turn, be shaped by it.

What has survived of this over time? Not the glamour of stars, the sentimental dialogue, the latest fashions in dance—the twist or the cha cha—the music—rock-and-roll with Elvis and then the incomparable Beatles—the clothes—bell-bottoms and flappers, slinky saris with choli blouses—the hair styles—beehive and bouffant—all of which we lapped up greedily. Not the gyrating with abandon to the heady tunes behind closed doors and having our adolescent beehives undone before we even stepped out of the house by Baiji, my determined grandmother who—may her censor’s soul rest in heaven—had eyes in the back of her head that, unlike the myopic ones in front, had 20/20 vision for the many attempts at sneaking past her back as she sat on the prayer rug, supposedly concentrating on the hereafter.

These impressions, though formative, were temporary and lasted only through adolescence. What stayed was the possibility of other worlds and other lives that I lived in imagination enriching my obscure, rigidly structured existence in an end-of-the-world Sialkot—the subversive inkling that there could be more than what was around me. This lesson I learned through osmosis in spite of reinforcement to the contrary by the environment, especially by Baiji and the other women of the extended household who let no opportunity go by to delineate, explain, and justify proper behavior and prescribe appropriate desires for a good Muslim girl in a good middle-class family in the newly-emerged Islamic Republic of Pakistan.