by Bill Murray

The crocodiles know. They form pincers on either side of the crossing point. Richard says they feel the vibration of all those hooves along the riverbank above them.

The crocodiles know. They form pincers on either side of the crossing point. Richard says they feel the vibration of all those hooves along the riverbank above them.

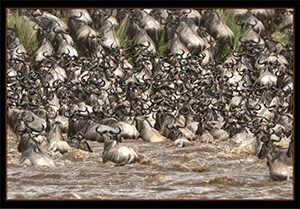

Waves of animals surge toward the river then fall away. If they all go we’ll witness a frightful, deadly crush of beasts in motion, mad energy, herd hysteria, dust and confusion, the cries of mortally wounded beasts rising to the heavens, birds of prey gaggling and swooping and squawking, kinetic intensity unbound.

We have come to see the sprawling, real life spectacle of wildebeests crossing the Mara River. It is the largest overland migration in the world.

•••••

Before dawn odd factory sounds waft across the river from behind a stand of trees. The explanation rises as a fire-breathing, tourist-wielding hot air balloon.

Stiff northerly winds will make for a short flight because the pilot must put down before the Tanzanian border, and you can see Tanzania from here. Wherever they land, champagne breakfast will be served on a folding table covered by a Maasai blanket, delivered by Land Rovers even now in mad pursuit.

“Are you strong?”

It is our driver/guide Richard’s pre-dawn battle cry, out by the Land Rover.

We are.

You begin every safari getting to know the back of your driver/guide’s head, your little team finding its groove for twelve-hour days spent in close quarters. Richard wears an oversized green jacket and a standard issue ball cap with the camp logo, and he parcels out his words with care.

We ask questions ripe for elaboration:

“Do you drive around film crews sometimes?”

Richard replies, “Yes.”

“Odd tree there. Is it a type of baobab?”

“It’s a fig tree or something.”

Richard doesn’t care much about the botany that’s required knowledge for today’s tourism college graduates. His strength is twenty five years on home ground, ten thousand days driving these plains.

•••••

The Mara River flows fast and muddy brown, fed from the Mau escarpment that runs as high as 10,000 feet from Nakuru town in Kenya all the way down to Tanzania. Sometimes its banks slope up in sandy transition zones, but more often downcutting has created serrated edges. Grass along the cliffs is grazed tight, testimony to the herds’ frequent presence and repeated dalliances with crossing.

The gamut of plains antelopes falls in for morning inspection. Topi stand as topi do on termite mounds, itchy but seizing a meter’s worth of improved view, with plum flanks and black snouts, kin to the handsome Sassebees down south.

While the eland species found in Kenya is called the common eland, it is anything but, a huge thing, a sight to behold, its majestic horns spiraling over a dewlap, a bulge of skin under the jaw akin to the vocal sac of a bullfrog or the pelican’s fish-stash pouch. The eland’s stripes suggest white paint dropped from above and drizzled down its flanks.

Each dawn reveals the previous night’s kills. The plains brim with food just now, and after the principal predator has its fill – a lion, a pack of hyenas – avian beak and claw devour the remains. The corpse is beset by a horde of vultures, maribous and bustards. Among them, every prospective bite involves mortal combat.

A martial eagle protects its own kill, neck thick and pulsing, straddling raw meat. Not your most handsome bird, this one, more workmanlike than noble, with obvious physical prowess. Burly, rippling with muscle. And a cannibal. Even those huge storks that nest atop phone poles in the northern part of Europe “are recorded to have fallen prey to the martial eagle.” Poor little guinea fowl are just snacks.

An impala calf? That’s a banquet.

We drive and we drive from the river to hills and back, and we are forever in the midst of wildebeests. Richard stops the Land Rover and shakes his head. “One year we had the big number. But to me I think this is the biggest. This must be a million.” We are among so many bearded beests that there must be no more anywhere on earth. They are all here.

•••••

Yellow is the color of the savannah from here north to the Sahel. The classic plains vista, yellow under blue, lacks only the umbrella acacias found farther north. This time of year the grass across the Mara River really is greener on the other side, as the wildebeest migration follows the rains.

Showers play over the Tanzania end of the escarpment. Called the Maasai Mara in Kenya and the Serengeti in Tanzania, this ecosystem is all the same place, and the escarpment is its western marker.

Storms throw the herd into confusion as auditory cues go missing. A tempest brews out of forbidding darkness, a furious squall, and the wildebeests move toward the rain. Before long it is hard to tell if the tracks on which Richard drives are roads or rivers.

The rain is the reason the herds are here. It brings the grasses back to life. A biologist named Richard Bell determined the process: zebras lead and the wildebeests follow, trailed by gazelles.

Zebras strip away the tops of tall, coarse grasses which those who follow find hard to digest. Wildebeests ruminate on the shorter, revealed grasses, their broad muzzle and loose lips adapted to bulk feeding. Gazelles follow to eat the most protein-rich shoots and sprouts. A rather more scientific explanation, “Grazing Succession of Ungulates in Western Serengeti,” won Bell his PhD in the 1960s.

•••••

Watch the herd’s behavior. If it moves toward the river, Richard says follow, but stay back. To approach the water’s edge too soon is hubris. You don’t know where they will cross, they don’t know, and a noisy machine on the cliff might put them off entirely.

Watch the herd’s behavior. If it moves toward the river, Richard says follow, but stay back. To approach the water’s edge too soon is hubris. You don’t know where they will cross, they don’t know, and a noisy machine on the cliff might put them off entirely.

Look for the beests to form up into a line. It doesn’t presage a crossing but it is a first indication. Zebras, even just a pair, will start the move toward water. Again and again queues will form, swaying one way and then the other, farragos of tentative intent drawn to the precipice.

Knots of animals gather and disperse a dozen times, but it is scarcely eight o’clock in the morning. Warmth hasn’t taken full hold; the beests won’t yet be thirsty, won’t be inclined to come down to the water for a drink.

A crossing will take a while. Patience.

•••••

The other day a train drove 60 miles across Australia with no one aboard, and it’s not clear if anyone is engineering this river crossing either. Whenever the beests cross, some will wind up crushed between the jaws of crocodiles. Does the herd know that crossing a river seeded with predators is mortal business?

Bees wouldn’t. Ants wouldn’t. Their tiny brains don’t do complex decision-making, but individual bees and ants, genetically predisposed to carry out duties associated with a few jobs – ‘guards,’ ‘workers,’ ‘scouts’ – collaborate to create colonies. Termites form mounds the same way. Collectively, they get things done.

After the space shuttle Challenger’s explosion “(t)he stock market did not pause to mourn.” Stocks of four contractors suffered losses but Morton Thiokol’s was the hardest hit, down four times as much as the others’. There was no immediate evidence Thiokol was to blame but six months later a presidential commission fingered the O-rings made by Thiokol. The market had it right in the first half hour.

Will the herd make the most efficient choice? Once an individual jumps into the water the rest will follow. All it takes is one. A single match will start a conflagration, and the instigator can be anybody, even a youngster. One act begets the next. Like the wave performed at ball games, a determined few can incite the crowd.

Could it be that the general movement of a herd (or a school of fish or a murmuration of starlings) is comparable to the way a brain thinks? An individual neuron doesn’t generate an opinion, but the collection of neurons called the brain, eventually does.

•••••

The sun is back by mid-morning. A group of beests congregates near the edge. Ours and other vehicles draw back from the crossing point called Double Cross where a tributary debouches into the Mara.

The pace quickens; animals bunch up. A thousand wildebeests pull away and the herd is diminished by half. Some vehicles leave but Richard won’t budge and he is right. After a time the animals (trailed by the vehicles) come back to stand on high ground at the precipice.

One zebra climbs down. More. The herd grows frantic and … pandemonium, dashing, mad splashing, and in the end we reckon 2000 animals cross, and it is all over fifteen minutes past noon.

We’ve seen a crossing our first morning. There’s nothing to this.

Self-satisfied, we break out a cooler full of Tuskers, but before the first beer is open a bit of a challenge raises its hooded head over the cliff and commands our rapt attention. A spitting cobra moves onto the ground along the Land Rover’s passenger side. This evil thing is longer than I am tall. Truth be told, other than its considerable length it looks about like the next snake.

It is not.

“Aggressive and poisonous,” Richard, our man of clipped vocabulary, remarks.

These cobras track their prey’s head movement, predicting where its eyes will be 200 milliseconds ahead of time and rotate their heads prior to ejecting venom “to cover a plane of probability.”

This particular cobra has immediate command over the humans in the Land Rover. As it makes its way over the bank ahead of us, along the side of the vehicle and into a hole in the dirt behind us, we scrunch over in the middle of the Land Rover away from the doors. As soon as the thing disappears head first into its lair, Richard starts the Land Rover and we flee.

•••••

The infantry soldier in the Great War’s trenches spent “months of boredom punctuated by moments of terror.” The terror side of the analogy works with the cobra, but the boredom part breaks down, for it is impossible to be bored watching tens of thousands of animals on an African plain.

During the afternoon, while we wait, Richard talks about life. Friends of his have been attacked by hippo or buffalo, some killed. He just lost his father two months ago and at this we stiffen and wince; he is still grieving and we had no idea. Richard’s father was only sick a few weeks and they don’t know why he died. So many African tragedies.

•••••

An hour before sunset the hunt is on again. A distant line of wildebeests is on the move, covering ground, driving, attracting adherents, surging to become a single feral statement. Vehicles move parallel until the herd stampedes itself into precarity, storming a peninsula, thundering to an abrupt halt.

An hour before sunset the hunt is on again. A distant line of wildebeests is on the move, covering ground, driving, attracting adherents, surging to become a single feral statement. Vehicles move parallel until the herd stampedes itself into precarity, storming a peninsula, thundering to an abrupt halt.

Crocodiles wait below, unmoving, dinosaurs poised for dinner.

The to and fro, the collective heartbeat, resumes. Richard fancies they are seeking consensus. If the caprice of one callow gnu can set off mass death, might wizened elders be conjuring undetectable hindering tricks? Perhaps the wisdom of crowds manifests too in mass group restraint.

Thousands of wildebeests paw the soil, driven to the edge, nervous, twitching. In fast-fading light the beests’ faces take on spectral shadow, the whole heaving mass willing itself, just one of itself, to hurl its body into the water, for all the rest to follow.

Not one of them does. The herd plays with fire but no one lights the match.

•••••

Gray light and a chill morning wind yield to midday sun. Richard raises his field glasses and sees a “huge group” ahead. “Thousands and thousands,” he says, and steers us toward a hilltop, seeking enough distance to discern direction of movement.

Far back along the savannah, an endless queue moves in mostly orderly pilgrimage. The vanguard collects into a grazing mass at the riverbank. A camp called Serena looks like haphazard prefab houses along the opposite ridge.

This herd is assertive from the start, muscular, not tentative like before, determined to cross, with strength in its numbers. Congregations merge and the entire mass moves toward a spot with easy-sloping banks, but all these beests spread well wide of the chosen point.

We are surrounded, swallowed up. The spearhead turns the riverbank to a seething, febrile froth, and in an instant, mayhem! Thundering and diving and rending noises, splashing and motion, bedlam you have never seen. Waves of beests hurl themselves over cliffs up and down the river. They press ahead. A half hour, a herd in motion, and then still more, no rear guard, ranks replenished over and over and then again.

The biggest crossing of the season.

The biggest crossing of the season.

On the far bank the herd emerges at a sprint. Individuals do not reconstitute into a group until far up onto the plain. A few emerge hobbled, limbs broken by the jump from the cliff or the crush of bodies. Some wildebeests are taken by crocodiles.

The aftermath continues an hour, and more. Mothers and offspring separated by the frenzy search for one another. Some mothers come to the far bank and look this way, imploring their young to appear. Will they cross back this way?

A few do. Most do not.

In time, zebras venture back to the far bank to drink. They were the cocky ones in the first place; they still have the swagger. Crocodiles lay at the water’s edge and do not attack. Are they sated from yesterday or rattled by what just happened, the movement and tumult and noise? A pair of giraffes approach the water but do not drink.

What do you think, was it five thousand, six?

More, Richard replies. Many more.