by Jalees Rehman

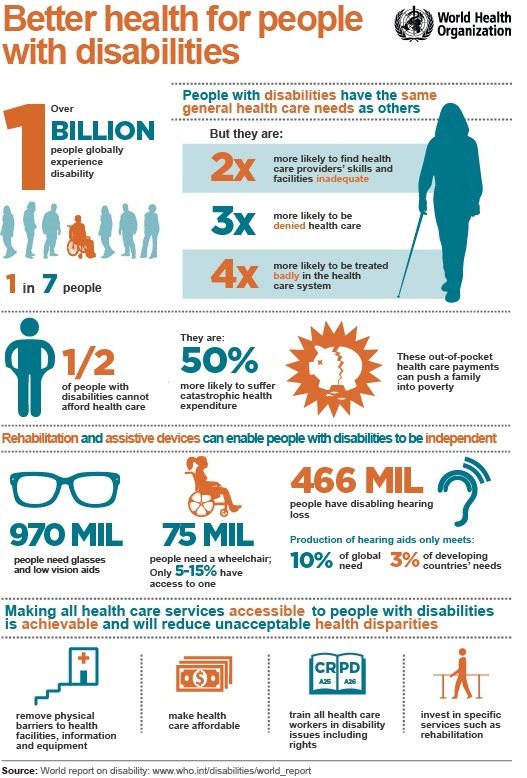

The World Health Organization (WHO) estimates that over a billion people live with some form of disability, expressed as impairments, activity limitations and participation restrictions. Disabilities are often manifestations of health conditions and as such, people suffering from disabilities not only require general medical care such as immunizations and preventive screenings but also need additional care to address the underlying health conditions. According to the WHO, people with disabilities are far more likely to suffer catastrophic health expenditures and receive inadequate medical care than people without disabilities. In addition to the medical and financial challenges, people with disabilities are often isolated and marginalized in society. The lack of political participation by people with disabilities in politics is especially concerning because it sets in motion a vicious cycle of marginalization. If the voices of people with disabilities are not adequately represented in the political arena, then it becomes less likely that governmental measures are taken to ensure adequate medical care and social integration of people with disabilities.

The researchers Lisa Schur and Meera Adya recently studied the political participation of people with disabilities in the United States in their article Sidelined or Mainstreamed? Political Participation and Attitudes of People with Disabilities in the United States. They used data from four US surveys: the 2008 and 2010 Current Population Surveys (CPS), the 2006 General Social Survey (GSS), and the 2007 Maxwell Poll on Citizenship and Inequality. The surveys ask respondents whether they suffer from distinct forms of impairment such as visual, hearing, mental-cognitive or mobility. There were 12,027 people in the 2008 CPS and 12,064 people in the 2010 who answered yes to at least one of the disability questions. The large sample size of CPS and the inclusion of a “voting supplement” in the CPS during even-numbered years allowed the researchers to study the extent of political participation by people with disabilities.

Schur and Adya found that the 2008 CPS showed significantly lower rates of voting among citizens with disabilities (64.5%) than those without disabilities (57.3%). Importantly, the type of disability determined the “disability gap” in voting. For example, hearing disability had a minimal effect on the likelihood of voting (63.1%) whereas mental disability (46.1%) or difficulties going outside alone (45.7%) resulted in major reductions of voting. The “disability gap” in 2010 was smaller but the overall rate of political participation was also much lower, possibly because it was a US midterm election and not a presidential election such as in 2008. People with disabilities were also less likely to attend meetings where political issues were discussed or participate in political rallies and marches. The fact that the type of disability impacted voting may also provide some clues as to how disabilities become barriers for political participation. The researchers suggest that a lot of political information is provided in written or other visual formats and may thus be more accessible to those with hearing impairments than other impairments. Furthermore, people with hearing impairments are likely to face less social stigma and marginalization than people with other disabilities.

On the other hand, physical or mental disabilities that make it difficult to leave the house alone represent logistical barriers for political participation. Potential voters with these disabilities may not have access to political meetings and information and may also lack the means of transportation to physically go to a polling station. Even though mail-in ballots are available in the United States, the procedure to request the mail-in ballots and obtain the political information about candidates may appear to be very cumbersome and represent insurmountable hurdles to people who have a history of being marginalized and isolated.

The GSS and Maxwell Polls allowed Schur and Adya to also query the political affiliation of the respondents. Interestingly, they found that there were no significant differences in their preference for the Republican versus the Democrat candidates. Even though, for example, people with disabilities were slightly more likely to vote for the Democratic candidate Kerry (50.6%) in the 2004 US presidential election than for the Republican candidate Bush (47.8%), this difference was no longer present once the researchers controlled for education, income, and demographic factors. The political affiliations of people with and without disabilities also did not appear to be significantly different. This suggests that people with disabilities are not intrinsically more likely to vote for one party, but that their vote may depend on the political issues that are on the ballot.

Schur and Adya estimate that “there would have been 3.0 million more voters in 2008, and 3.2 million more voters in 2010 if people with disabilities voted at the same rate as nondisabled people of similar age, gender, race/ethnicity, and marital status“. Even when the researchers controlled for education (because lower levels of education in the group of citizens with disabilities may have contributed to their lower rates of voting), they found that there would have been approximately two million more voters if one could help people with disabilities achieve similar voting rates as those of people without disabilities.

Elections in the United States are often swayed by much smaller margins than two million votes. This research really highlights the importance of integrating people with disabilities into the political process. Society needs to ensure that they can exert their right to vote. The long-term solutions require fundamental approaches that reduce the general stigma of disability and creating infrastructures which allow individuals with all forms of disability to receive adequate information about elections and receive assistance so that they can vote by mail or at polling stations. As a short-term fix, we as individuals should find ways to ask neighbors, friends and family members with disabilities whether we can offer any form of aid on election day.

Issues such as healthcare are currently at the forefront of the political debate in the United States and the elections could thus have a significant impact on the lives of people with chronic health conditions and disabilities. Our communities benefit when everyone’s voice is heard, especially those who are the most vulnerable. Although the extent of true political conversation and debate may be limited, in an election the vote is that voice. Let us work to maximize opportunities for every voice to be heard and every vote counted.

Reference

Schur, L., & Adya, M. (2013). Sidelined or Mainstreamed? Political Participation and Attitudes of People with Disabilities in the United States. Social Science Quarterly, 94(3), 811-839.