by Brooks Riley

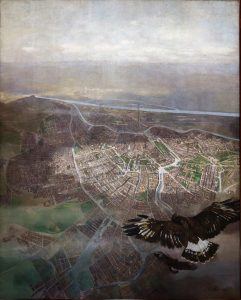

When architect Otto Wagner commissioned this large painting by Carl Moll for the Kaiser’s personal railroad station in Vienna in 1899, he might not have seen the irony of an eagle’s view of the city. View of Vienna from a Balloon envisions a future beyond rails in which a bird shows the way to a whole new way of looking at landscape, one that would renew the way we view nature itself, hardly more than a 100 years later. If that painting were done today, the eagle would be replaced by a small four-cornered device with a camera and four rotary blades to keep it aloft: the drone.

When architect Otto Wagner commissioned this large painting by Carl Moll for the Kaiser’s personal railroad station in Vienna in 1899, he might not have seen the irony of an eagle’s view of the city. View of Vienna from a Balloon envisions a future beyond rails in which a bird shows the way to a whole new way of looking at landscape, one that would renew the way we view nature itself, hardly more than a 100 years later. If that painting were done today, the eagle would be replaced by a small four-cornered device with a camera and four rotary blades to keep it aloft: the drone.

The relationship between human beings and nature has always been tense. While we acknowledge our debt to nature—our existence, our food, building materials, environment, panoramic views, flora and fauna, chromatic infinity, physical and biological laws—there is always some corner of our thinking that cries out, ‘Anything you can do I can do better,’ to quote an Irving Berlin song. When it comes to art, we set ourselves on a collision course with nature, touting our museum landscapes over the real ones and the painter’s vision as the one true aesthetic version of beauty. Now that we’ve left nature behind (in more ways than one), nature has left the building and moved into the brand new Instagram showroom where it can show itself off with impunity from interpretation.

The recognition of nature as a generator of beauty is universal. Representational art and photography are often tributes to that beauty—pyrrhic undertakings when the original is so compelling. And yet careers have been made from the depiction of nature—Caspar David Friedrich, Ansel Adams, and countless others. If our art differs from nature, it is in the selectivity and execution of the image as much as it is the subject matter. Art is our way of saying to nature, we can do better than you.

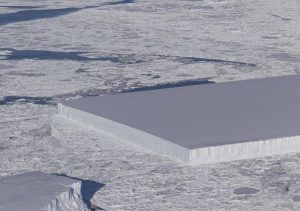

Image art isolates content. For that we need the frame, or the quadrangle–the one thing we do better than nature, whether square or rectangular. So rare is this form in nature that when a rectangular slab of ice was spotted from the space station a few weeks ago, it made headlines.

Image art isolates content. For that we need the frame, or the quadrangle–the one thing we do better than nature, whether square or rectangular. So rare is this form in nature that when a rectangular slab of ice was spotted from the space station a few weeks ago, it made headlines.

Years ago, my mother visited a jungle in Panama and photographed a square tree. Without that luminous color slide (where is it now?), I would not have believed her. A brief description in Atlas Obscura:

With hard right angles, rarely seen in nature, the trees have baffled visitors. Even the “rings,” of the interior tree grow in a square shape and not the typical circle, making the trees truly stick out in nature’s typical curvilinear palette.

The quadrangle, so seldom in nature, belongs to us. It’s what we do. Not only do we build the boxes we reside in, and write on quadrate pieces of paper, but we are the inventors of the four-cornered frame. And it is this ubiquitous frame that separates us from ‘nature’s typical curvilinear palette’, and from nature itself. The quadrate frame has allowed us to defy the properties of the human eye, to declare that one’s vision stops here, to consciously limit our focus to the contents of a frame and the world it contains—not all the time, but increasingly so, as we peer at the frames of our smart phones or laptops, the frames of our selfies, the frames of the paintings in a museum, the frames of our TV screens, the frame of a billboard or traffic signs. We rarely use the eye the way it was designed to be used, with the field of vision spreading out to the periphery and beyond. Vision is broadly oriented, offering context to the chosen focus: Even as we home in on an object, the eye is poised to see what’s on the edge of that object, and all around it. These days we use that wide lens only occasionally, to get our bearings or to enjoy a view—like a wide establishing shot in a film—necessary, but immediately dispensable as we go back to our frames.

Frames are a way of defining focus, of establishing its limits. A painting does not spread to the periphery, it occupies a space within four corners (rarely a circle). Why this is, has much to do with history. Our ancestors painted on cave walls without regard for formal rules of display. The Greeks painted on everything, from bowls to amphorae to buildings. But sometime thereafter, the quadrate became the most convenient means of representation, almost as though the painter already knew that photography would necessarily use the same form, the capture form of a rectangle. Early on, papyrus, parchment and eventually paper were quadrate, the most efficient way to transcribe language.

Photography introduced the frame to real life, taking it out of the museums and churches, and putting it on our tables, our walls, and in our books and photo albums. Aesthetic or not, the image within the frame came to define a place, a moment, a person, the content the result of a conscious choice.

In the digital age, even pixels are quadrate. If one can imagine a digital photograph as a carpet or quilt of tiny squares, then it’s not inconceivable to see the earth’s surface as such, with millions of pixels, and millions of bigger squares to be isolated and documented. This is what drone photographers do, curating the endless number of images available to the drone camera and isolating them within a frame of view that transforms them into something that looks like art. Are they artists? Yes, in the sense that they select what will fill the frame. Can you hang their work on a wall? Yes—at least some of them.

Until now, the contemplation of natural beauty has always been horizontal—nature seen from eye level. It’s one of the reasons people flock to high places—mountain tops, skyscrapers—not just to see more, but to shift the angle of our horizontal gaze just enough to engender the ‘aha’ moment. What we really want are wings. But unlike Daedalus and Icarus, it’s escapism we’re after, not escape.

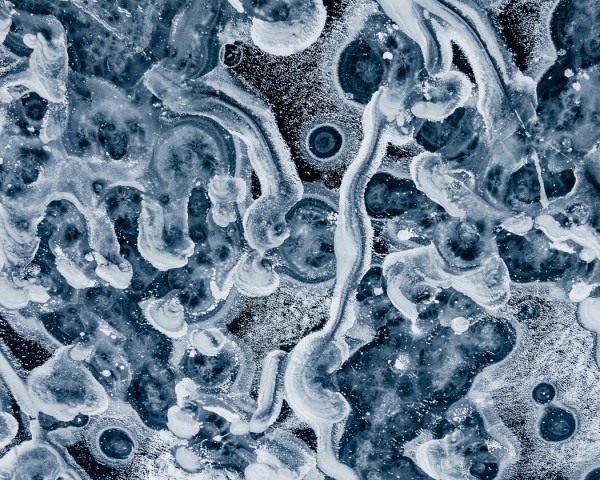

Drone photography could be described as a collaboration or a co-production between man and nature. It allows nature to speak on its own terms but in a novel new way. If photomicrography undresses nature, drone photography with its plumb-line overhead view shows us nature at an angle we’ve never seen before, exposing its pixel treasures, many of which throw a shade over any abstract art produced by an artist.

In ancient times, it took a quantum leap of the imagination to infer the visual information drones would eventually deliver. It began with cartography, the extreme view from above, one of man’s oldest pictorial urges to satisfy an everlasting curiosity about the world we occupy. Mapmaking was undertaken by visionaries in all cultures, on all continents, the oldest known map dating back 25,000 years. Maps derived from a combination of knowledge and imagination, with a fair measure of extrapolating thrown in until we knew more.

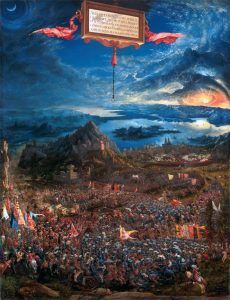

As artistic endeavor advanced, its aim to insert us into that world brought the point-of-view closer to bird’s-eye level, to an indeterminate altitude above the action. The bird’s eye view in art has been around for centuries, lurking in artistic visions aiming to achieve the all-important overview of things, while not forgetting the dramatis personae. Artists know that the higher they are from ground level, the more can be seen, the richer the field of vision. A higher angle provides volumes of new information that the horizontal gaze cannot deliver. If not quite the plumb-line vertical view of recent drone photography, paintings often depicted extreme angles that no mountain elevation could have afforded, suggesting that the artist was indeed a bird/drone in his own mind. Renaissance painter Albrecht Altdorfer’s Battle of Alexander at Issus is such a painting, with its exponential depth of field, its riotous depiction of multiple locations, conflicting military strategies, crisscrossing battalions, and varying landscapes dotted with mountains and towns made diminutive by his own much higher standpoint on a mountain of his invention.

Seventeenth-century Japanese Edo screen paintings of the Edo castle and the siege of Osaka reveal sophisticated innate knowledge of the view from up there. Dürer too understood the fly-on-the-ceiling take on great events, as I mentioned in an earlier post. Oskar Laske, painter and student of Otto Wagner, used this god’s-eye angle more than once for his cynical take on mankind in a series of paintings all called Ship of Fools.

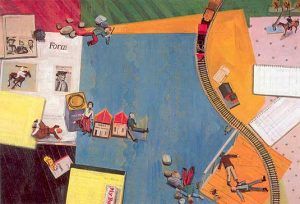

The first vertical drone photograph I remember seeing—an overhead shot of a beach with umbrellas, sunbathers, ocean waves—brought to mind the paintings of Manny Farber, notably his table-top series, random objects and scaled-down figures on a table seen from above. Farber was best known as a film critic, one of the field’s most idiosyncratic. As a man of visual acuity, he plumbed his past and his profession for the icons to place on these ‘tables of content’, turning them into figures linked by a train track in a landscape resembling the intricate map of his own bifurcated mind.

The first vertical drone photograph I remember seeing—an overhead shot of a beach with umbrellas, sunbathers, ocean waves—brought to mind the paintings of Manny Farber, notably his table-top series, random objects and scaled-down figures on a table seen from above. Farber was best known as a film critic, one of the field’s most idiosyncratic. As a man of visual acuity, he plumbed his past and his profession for the icons to place on these ‘tables of content’, turning them into figures linked by a train track in a landscape resembling the intricate map of his own bifurcated mind.

He was not the first or the last to troll the deep yearning in our genes for a bird’s eye view. Kurt Schwitters, Juan Gris, and many other artists have understood the power of vertigo.

Even this 1990 painting by Dutch painter Fons Heijnsbroek, Abstract Landscape with Sunlight, seems to presage the color palate and viewpoint that would find its twin in a drone photograph taken decades later in Neuhof, Germany.

What drone photography has to offer goes far beyond the spectacular abstract ‘paintings’ it culls from a landscape. The vertical view means that anything perpendicular to the ground, or rising from the ground—a building, a fir tree, a tower—seems to be coming toward us. This gives certain drone photographs a passive 3D effect less evident in a horizontal perspective.

Trompe l’oeil is another accidental by-product of the vertical view as shadows suddenly upstage their progenitors. The artist Saype has already harnessed this attribute to create a massive trompe l’oeil land art fresco in Geneva that functions only when seen at drone level.

In drone photography, depth of field enhances the drama of the vertiginous view, a subtle kinetic effect. And even flat surfaces can come alive if something is happening in the picture: a worker rakes drying chili peppers across the grain, adding action to what would otherwise be a still-life abstract.

If drone photography is a radical new aesthetic, it is not only because of its endless possibilities, but because its new point of view represents the ultimate fulfilment of our oldest dream, to fly like a bird and look down. Whether or not it will establish itself in our visual vocabulary depends on the pictures themselves and how much imagination this aesthetic can accommodate. Will the vertical shot slowly lose its appeal, like 3D has each time it’s trotted out as the next best thing? Drone cinematography is comfortably ensconced into movie language as a viable alternative for the crane shot or helicopter shot. But drone photography may have to one-up itself to keep us hanging in the air by our toenails.