by Bill Murray

In the middle of the night of March 24, 1992, a pressure seal failed in the number three unit of the Leningradskaya Nuclear Power Plant at Sosnoviy Bor, Russia, releasing radioactive gases. With a friend, I had train tickets from Tallinn, in newly independent Estonia, to St. Petersburg the next day. That would take us within twenty kilometers of the plant. The legacy of Soviet management at Chernobyl a few years before set up a fraught decision whether or not to take the train.

In the middle of the night of March 24, 1992, a pressure seal failed in the number three unit of the Leningradskaya Nuclear Power Plant at Sosnoviy Bor, Russia, releasing radioactive gases. With a friend, I had train tickets from Tallinn, in newly independent Estonia, to St. Petersburg the next day. That would take us within twenty kilometers of the plant. The legacy of Soviet management at Chernobyl a few years before set up a fraught decision whether or not to take the train.

Monitoring stations in Finland detected higher than normal readings. The level of iodine-131 at Lovisa, Finland, just across the gulf, was 1,000 times higher than before the accident, according to the German Institute for Applied Ecology.

Russian authorities reported the accident in the media, and I think they felt self-satisfied for doing it, but Russian credibility had burned down with Chernobyl’s reactor 4. Any more, people thought the Soviets, as Seymour Hersh said about Henry Kissinger, lied like other people breathe. And as usual, solid information was hard to come by.

A news agency in St. Petersburg reported increased radiation, and the Swedish news reported panic in St. Petersburg. A lady in Tallinn that day told me her mother had called from St. Petersburg and they were closing the schools and sending children home to stay indoors. The Finnish Prime Minister fussed that seven hours passed before the Russians told him. It was frightening.

No one believed the plant spokesman when he said on TV, hey (big Soviet smile), no problem. No one trusted the Russians. Read more »

It’s been a while since I posted on this issue, and I’ve already said most of what I intended to say about it, but things seem to be coming to a head in my own state, and I thought I’d report on that, including a couple of weird local wrinkles (the Garden State is a strange place). Three weeks ago, after months of missed deadlines, an adult-use marijuana legalization bill was approved by a joint (Assembly/Senate, that is, not … never mind) committee of the legislature, and may (note: may) be voted on later this year. If it is passed and signed into law by the governor – neither of which is a given – New Jersey would be the eleventh state to legalize adult use, and the second to do so by legislative action. (Washington and Colorado in 2012, Alaska and Oregon in 2014, California, Massachusetts, Maine, and Nevada in 2016, and Michigan in 2018 did so by voter referendum; Vermont did so by legislative action (in 2017, I think), although that state’s bill did not set up a legal market, which means that while it is legal to grow marijuana in one’s basement there, it remains illegal to buy seeds to do so.)

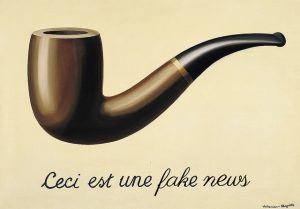

It’s been a while since I posted on this issue, and I’ve already said most of what I intended to say about it, but things seem to be coming to a head in my own state, and I thought I’d report on that, including a couple of weird local wrinkles (the Garden State is a strange place). Three weeks ago, after months of missed deadlines, an adult-use marijuana legalization bill was approved by a joint (Assembly/Senate, that is, not … never mind) committee of the legislature, and may (note: may) be voted on later this year. If it is passed and signed into law by the governor – neither of which is a given – New Jersey would be the eleventh state to legalize adult use, and the second to do so by legislative action. (Washington and Colorado in 2012, Alaska and Oregon in 2014, California, Massachusetts, Maine, and Nevada in 2016, and Michigan in 2018 did so by voter referendum; Vermont did so by legislative action (in 2017, I think), although that state’s bill did not set up a legal market, which means that while it is legal to grow marijuana in one’s basement there, it remains illegal to buy seeds to do so.) I met Rene Magritte a few weeks ago at the Starline Social Club in Oakland. A surprisingly jolly fellow, it turns out he’s working these days as a pedicab driver in San Francisco. Surrealism isn’t my jam, but when he offered me a pickup the next morning at the BART and mushrooms and tickets for two to the retrospective of his work at SFMoMA, well—I had to accept.

I met Rene Magritte a few weeks ago at the Starline Social Club in Oakland. A surprisingly jolly fellow, it turns out he’s working these days as a pedicab driver in San Francisco. Surrealism isn’t my jam, but when he offered me a pickup the next morning at the BART and mushrooms and tickets for two to the retrospective of his work at SFMoMA, well—I had to accept.

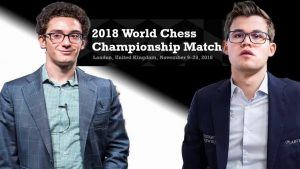

Magnus Carlsen and Fabiano Caruana faced off for the World Chess Championship over three weeks London. I’d been looking forward to the match all year, and following the progress of the two players towards it. This piece looks at the two players and the situation before the match, gives an account of the Championship games, and concludes with some reflections on the significance of the match for the participants, and for the sport.

Magnus Carlsen and Fabiano Caruana faced off for the World Chess Championship over three weeks London. I’d been looking forward to the match all year, and following the progress of the two players towards it. This piece looks at the two players and the situation before the match, gives an account of the Championship games, and concludes with some reflections on the significance of the match for the participants, and for the sport. I recently rewatched “12 Angry Men” with The Philosophy Club at the University of Iowa as part of their “Owl of Minerva” film series. The 1957 film has the late, great Henry Fonda as the lone holdout on a jury ready to convict a poor, abused 18-year-old boy for allegedly stabbing his father to death. Over one long, tense evening (shown in something close to real-time), juror #8 – none of the jurors are identified by name, only number – forces the rest of the jury to methodically reexamined the evidence. It’s not a courtroom drama, it’s a jury-room drama in which only 3 of 1:36 minutes of running time take place outside the sweaty, claustrophobic jury room. The film is intense, moving, and effective. Afterwards, I made the following remarks.

I recently rewatched “12 Angry Men” with The Philosophy Club at the University of Iowa as part of their “Owl of Minerva” film series. The 1957 film has the late, great Henry Fonda as the lone holdout on a jury ready to convict a poor, abused 18-year-old boy for allegedly stabbing his father to death. Over one long, tense evening (shown in something close to real-time), juror #8 – none of the jurors are identified by name, only number – forces the rest of the jury to methodically reexamined the evidence. It’s not a courtroom drama, it’s a jury-room drama in which only 3 of 1:36 minutes of running time take place outside the sweaty, claustrophobic jury room. The film is intense, moving, and effective. Afterwards, I made the following remarks.

It’s getting colder now in Beijing, and I can’t help but feel for the clothing left outside to dry. They had to hang through the night and on through the weak sunrise, doing their best to catch the wind before the temperature drops again. How do they feel being out there for passers-by to see, all exposed, caught up in the dust and very small toxic particles?

It’s getting colder now in Beijing, and I can’t help but feel for the clothing left outside to dry. They had to hang through the night and on through the weak sunrise, doing their best to catch the wind before the temperature drops again. How do they feel being out there for passers-by to see, all exposed, caught up in the dust and very small toxic particles?

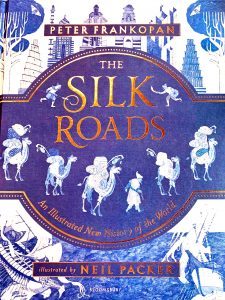

“You start with a scarf…each 90-by-90-centimeter silk carré, printed in Lyon on twill made from thread created by the label’s own silkworms, holds a story. Since 1937, almost 2,500 original artworks have been produced, such as a 19th-century street scene from Ruedu Faubourg St.-Honore, the company’s home since 1880. The flora and fauna of Texas. A beach in Spain’s Basque country” –- this is a fragment from an advertisement article for Hermès in this month’s issue of a luxury magazine. The article is called “The Silk Road.” Does it refer to the “Silk Road” in any way that justifies the title, beyond the allure of legend? No. Does it mention that the first scarves created for this very label, in 1937, were made with raw silk from China? No. Not necessary, not relevant to the target reader. In fact, the less we mention the “East” while trying to sell such luxury designer items, the better, aiming as we are for the rich collector, the global consumer of fashion (whether belonging to the East or West) willing to spend hundreds of dollars on a small square of silk, and more likely to associate such status symbols with Western Europe rather than with the “underdeveloped,” impoverished, overpopulated, conflict-ridden East.

“You start with a scarf…each 90-by-90-centimeter silk carré, printed in Lyon on twill made from thread created by the label’s own silkworms, holds a story. Since 1937, almost 2,500 original artworks have been produced, such as a 19th-century street scene from Ruedu Faubourg St.-Honore, the company’s home since 1880. The flora and fauna of Texas. A beach in Spain’s Basque country” –- this is a fragment from an advertisement article for Hermès in this month’s issue of a luxury magazine. The article is called “The Silk Road.” Does it refer to the “Silk Road” in any way that justifies the title, beyond the allure of legend? No. Does it mention that the first scarves created for this very label, in 1937, were made with raw silk from China? No. Not necessary, not relevant to the target reader. In fact, the less we mention the “East” while trying to sell such luxury designer items, the better, aiming as we are for the rich collector, the global consumer of fashion (whether belonging to the East or West) willing to spend hundreds of dollars on a small square of silk, and more likely to associate such status symbols with Western Europe rather than with the “underdeveloped,” impoverished, overpopulated, conflict-ridden East. A few months back my boss and I had lunch with the person who, wearing a t-shirt that read “black death spectacle”, stood in protest in front of a painting of Emmett Till by Dana Schutz called Open Casket at the last Whitney Biennial. Shortly after his gesture another artist penned an open letter about how Schutz’s painting uses “black pain” as a medium, and how this use by non-Black artists needs to go. I’m not sure what the ethical verdict is (of whether or not Schutz made a gravely racist error), or whether the artist’s letter voiced an instance of over-reaching aesthetic censorship, nor will I make any attempt at trying to resolve that issue here; it would take far more space than what is available and is not my aim. Consider reading Aruna D’Souza’s recent book Whitewalling: Art, Race & Protest in 3 Acts for a thorough treatment (which, not so incidentally, the above mentioned protestor provided images for).

A few months back my boss and I had lunch with the person who, wearing a t-shirt that read “black death spectacle”, stood in protest in front of a painting of Emmett Till by Dana Schutz called Open Casket at the last Whitney Biennial. Shortly after his gesture another artist penned an open letter about how Schutz’s painting uses “black pain” as a medium, and how this use by non-Black artists needs to go. I’m not sure what the ethical verdict is (of whether or not Schutz made a gravely racist error), or whether the artist’s letter voiced an instance of over-reaching aesthetic censorship, nor will I make any attempt at trying to resolve that issue here; it would take far more space than what is available and is not my aim. Consider reading Aruna D’Souza’s recent book Whitewalling: Art, Race & Protest in 3 Acts for a thorough treatment (which, not so incidentally, the above mentioned protestor provided images for).

Ever since my childhood I have been excited, even electrified, by movies. In my college days in Calcutta, in search of alternate experience beyond Indian and Hollywood movies, I used to frequent the local Film Society events, showing some commercially unavailable European fare. Short of funds these Film Society outfits mainly went for movies they could procure at low cost. The East European consulates in the city were particularly generous in making available films from their countries.

Ever since my childhood I have been excited, even electrified, by movies. In my college days in Calcutta, in search of alternate experience beyond Indian and Hollywood movies, I used to frequent the local Film Society events, showing some commercially unavailable European fare. Short of funds these Film Society outfits mainly went for movies they could procure at low cost. The East European consulates in the city were particularly generous in making available films from their countries. Many decades ago, I packed my bags and left the shores of Australia and headed to the United Kingdom (UK). My secondary years of education had taught me to believe that my journey to the UK would amount to a ‘return’ to the ‘motherland’. A ‘return to the motherland’? Really? That says more about the education system I was exposed to, than just how naïve I was. However, having learned after my arrival that the UK was not, in fact, my ‘motherland’, I did discern that it had more to offer in terms of being ‘in’ the world than the distant shores of Australia, and I decided to stay. Thus, after many years resident in the UK, I considered myself as someone familiar with the country, until, that is, a change in my life circumstances provided me the opportunity to know the UK, or more specifically, England, in a totally different way.

Many decades ago, I packed my bags and left the shores of Australia and headed to the United Kingdom (UK). My secondary years of education had taught me to believe that my journey to the UK would amount to a ‘return’ to the ‘motherland’. A ‘return to the motherland’? Really? That says more about the education system I was exposed to, than just how naïve I was. However, having learned after my arrival that the UK was not, in fact, my ‘motherland’, I did discern that it had more to offer in terms of being ‘in’ the world than the distant shores of Australia, and I decided to stay. Thus, after many years resident in the UK, I considered myself as someone familiar with the country, until, that is, a change in my life circumstances provided me the opportunity to know the UK, or more specifically, England, in a totally different way.

We can agree that a verb in the present tense means that action is occurring now. What about the present progressive, which I used in the previous statement? That apparently confounds non-native English speakers because it means that an action is in the middle of happening. Friends have asked me, “What is the difference between I am playing tennis and I play tennis?” That example is actually a softball because the present progressive indicates that the first person is in the middle of playing a game and the simple present indicates the playing of the sport in general.

We can agree that a verb in the present tense means that action is occurring now. What about the present progressive, which I used in the previous statement? That apparently confounds non-native English speakers because it means that an action is in the middle of happening. Friends have asked me, “What is the difference between I am playing tennis and I play tennis?” That example is actually a softball because the present progressive indicates that the first person is in the middle of playing a game and the simple present indicates the playing of the sport in general. Before the second was defined in terms of the characteristics of the cesium atom, before leap seconds or leap days or Julian dates or the Gregorian calendar, before clocks, even before the sundial and the hourglass, there were sunrise, sunset, and shadows.

Before the second was defined in terms of the characteristics of the cesium atom, before leap seconds or leap days or Julian dates or the Gregorian calendar, before clocks, even before the sundial and the hourglass, there were sunrise, sunset, and shadows.