by Shawn Crawford

In January of 1841, passengers arriving from Europe would be greeted by anxious New Yorkers on the docks. They all had the same question: “Is Little Nell dead?” Such was the anxiety caused by Charles Dickens’ novel The Old Curiosity Shop. But why couldn’t tortured New Yorkers simply read to the end of the book and relieve their fears?

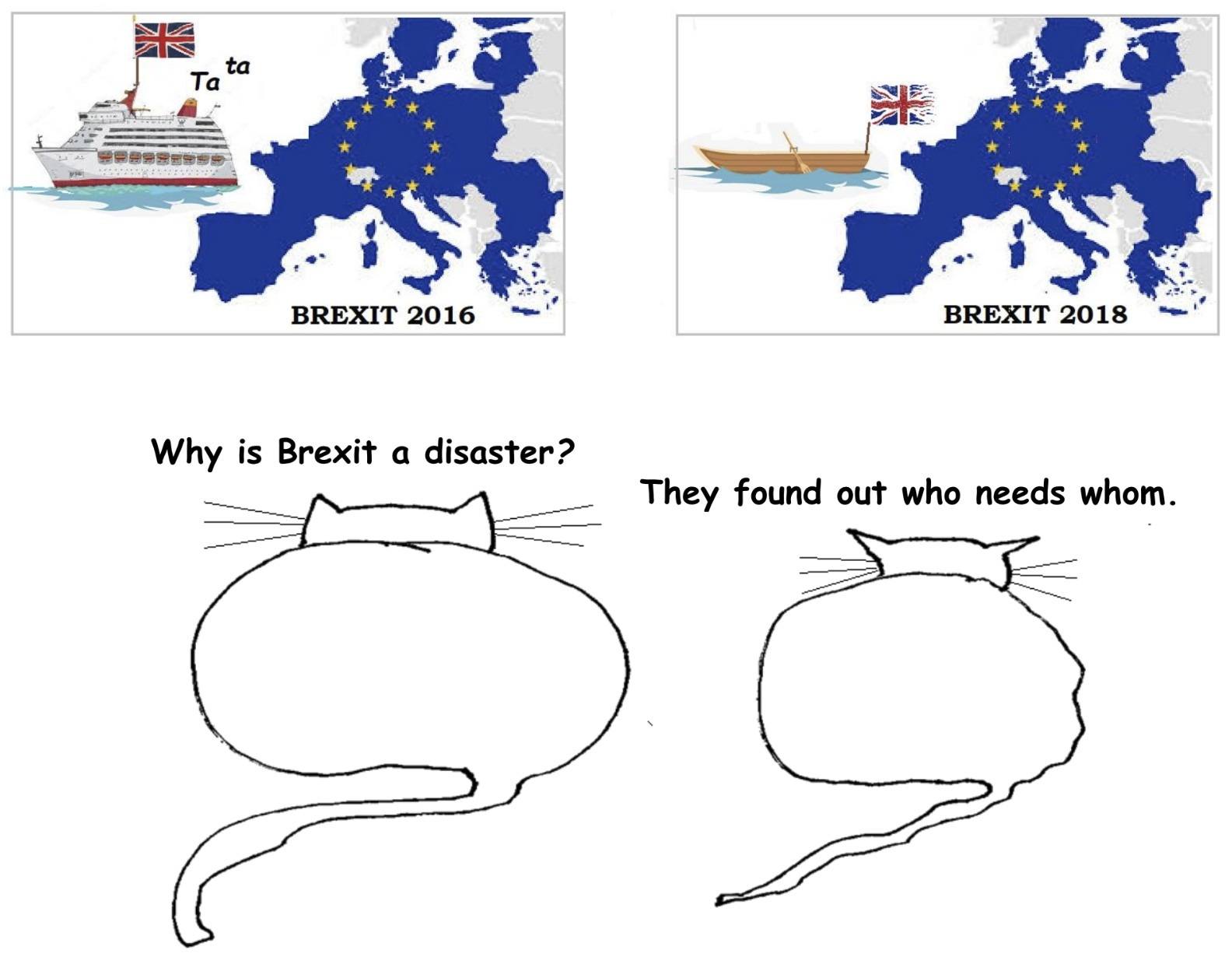

Dickens’ work, like many Victorian novels, originally saw publication in serial form. Released monthly in periodicals or stand-alone as “part issues”, normally in three to five chapter installments, serial novels kept the public guessing and agonizing for up to two years. From the serial we derive the term “cliffhanger,” coined for the fraught dilemmas characters found themselves in at the end of an installment. In the case of serial master Wilkie Collins, often literally hanging from a cliff or heading over a waterfall. Spoiler alert: Little Nell dies. Readers in London and New York wept on the streets as they finished the installment describing her fate.

While a brilliant economic strategy, after serialization you could sell the book, the serial novel also offered the perfect form to entrance Victorian audiences. As Linda K. Hughes and Michael Lund point out in The Victorian Serial, personal development became an obsession in the Victorian mind. Serial novels mirrored their belief that personal and cultural progress was gradual, positive, and inevitable. Read more »

Mandra health center, outside Islamabad, on this spring morning, without the cacophony and confusion of health centers in the city, was the picture of serenity. An emaciated woman of indeterminate age sits coughing in the corridor, in a chair that bears the logo of the United States Agency for International Development, next to a little girl with dry shoulder length hair and yellow eyes, one bare foot resting upon the other. I make a provisional diagnosis—pulmonary tuberculosis for the woman, viral hepatitis for the girl, both diseases endemic in Pakistan.

Mandra health center, outside Islamabad, on this spring morning, without the cacophony and confusion of health centers in the city, was the picture of serenity. An emaciated woman of indeterminate age sits coughing in the corridor, in a chair that bears the logo of the United States Agency for International Development, next to a little girl with dry shoulder length hair and yellow eyes, one bare foot resting upon the other. I make a provisional diagnosis—pulmonary tuberculosis for the woman, viral hepatitis for the girl, both diseases endemic in Pakistan.

From its origins in Eurasia some 8,000 years ago, wine has spread to become a staple at dinner tables throughout the world. Yet wine is more than just a beverage. People devote a lifetime to its study, spend fortunes tracking down rare bottles, and give up respectable, lucrative careers to spend their days on a tractor or hosing out barrels, while incurring the risk of making a product utterly dependent on the uncertainties of nature. For them, wine is an object of love.

From its origins in Eurasia some 8,000 years ago, wine has spread to become a staple at dinner tables throughout the world. Yet wine is more than just a beverage. People devote a lifetime to its study, spend fortunes tracking down rare bottles, and give up respectable, lucrative careers to spend their days on a tractor or hosing out barrels, while incurring the risk of making a product utterly dependent on the uncertainties of nature. For them, wine is an object of love. Academics have a privileged epistemic position in society. They deserve to be listened to, their claims believed, and their recommendations considered seriously. What they say about their subject of expertise is more likely to be true than what anyone else has to say about it.

Academics have a privileged epistemic position in society. They deserve to be listened to, their claims believed, and their recommendations considered seriously. What they say about their subject of expertise is more likely to be true than what anyone else has to say about it. The day before Thanksgiving I got this wonderfully understated text from a close friend:

The day before Thanksgiving I got this wonderfully understated text from a close friend:

Our uniform was a shirt tucked into jeans. Sandi stretched the smallest size over well-proportioned breasts, her black bra peeking through a run of buttons. Mine hung long in the sleeves and fell over my waist.

Our uniform was a shirt tucked into jeans. Sandi stretched the smallest size over well-proportioned breasts, her black bra peeking through a run of buttons. Mine hung long in the sleeves and fell over my waist.