by Holly Case

About 1,500 years ago, the Chinese literary critic Liu Hsieh wrote The Literary Mind. It includes a section on metaphor—hsing—which he describes as “response to a stimulus.”

[W]hen we respond to stimuli, we formulate our ideas according to the subtle influences we receive…. the hsing is an admonition expressed through an array of parables.

I first came upon The Literary Mind some months ago and was immediately fascinated by Hsieh’s elucidation of hsing, but will confess to having had no idea what he meant, even after studying his examples. It remained in the back of my mind.

Some time after discovering Hsieh, I was having a series of intense discussions with a group of students on the theme of apocalypse. Again and again, two of them mentioned a story by Ursula K. Le Guin from 1973 called “The Ones Who Walk Away from Omelas.” Omelas, Omelas, Omelas.

Some weeks later, the word “Omelas” occurring to me in flashes, I printed out a copy of the story and read it. You should read it. Omelas is a mythical city where the mood is festive and everything and everyone appear in good form and spirits. The narrator begins by describing and defending how Omelas functions as a great festival of summer unfolds in the background. “Do you believe? Do you accept the festival, the city, the joy?” the narrator asks the reader. “No? Then let me describe one more thing.”

In a basement under one of the beautiful public buildings of Omelas, or perhaps in the cellar of one of its spacious private homes, there is a room. It has one locked door, and no window.… In the room a child is sitting.… The door is always locked; and nobody ever comes, except that sometimes—the child has no understanding of time or interval—sometimes the door rattles terribly and opens, and a person, or several people, are there. One of them may come and kick the child to make it stand up. The others never come close, but peer in at it with frightened, disgusted eyes.… It is naked. Its buttocks and thighs are a mass of festered sores, as it sits in its own excrement continually. They all know it is there, all the people of Omelas. Some of them have come to see it, others are content merely to know it is there. They all know that it has to be there. Some of them understand why, and some do not, but they all understand that their happiness, the beauty of their city, the tenderness of their friendships, the health of their children, the wisdom of their scholars, the skill of their makers, even the abundance of their harvest and the kindly weathers of their skies, depend wholly on this child’s abominable misery.

Sometimes it happens that, after seeing the child, a person from Omelas sets out on a road that leads away from the city. And keeps walking. The story ends: “The place they go towards is a place even less imaginable to most of us than the city of happiness. I cannot describe it at all. It is possible that it does not exist. But they seem to know where they are going, the ones who walk away from Omelas.”

The story troubles me. It’s the leaving. What does leaving do for the child locked in the cellar? Read more »

![]() My wife and I live in the southern Appalachian mountains across a narrow valley from Georgia’s highest mountain. Most of our farm borders the United States Forest Service, pretty far up in the woods. If we don’t go out, we might not see anyone for a week.

My wife and I live in the southern Appalachian mountains across a narrow valley from Georgia’s highest mountain. Most of our farm borders the United States Forest Service, pretty far up in the woods. If we don’t go out, we might not see anyone for a week.

r a train and someone passed through begging for change. I’ve lived in New York City long enough that I don’t just start taking my wallet out and going through it in crowded public spaces, but beyond that, I don’t have change. I normally don’t carry cash. If I have cash on me its for one of two reasons, either someone has paid me back for something in cash (which in these days of Venmo is increasingly unlikely) or I have a hair or nail appointment where they like their tips in cash. So even if I have cash, it’s bigger bills and certainly no coins. And I’m sure I’m not unusual. I pay for things with credit cards. I pay other people using Apple Pay or Venmo. I mentioned this thought to someone who told me that they had seen someone begging in New York with details of their Venmo account. On the one hand, there seems to be a certain chutzpah to that, after all, if you have a bank account to receive the money in and some kind of smart phone to access it, is your situation as dire as you’re making out? On the other hand, it’s pretty smart. Of course, there are serious privacy issues involved in giving money to a random stranger through an app like Venmo, it’s not private, so I probably wouldn’t do that either, but it’s an interesting idea, if it could be made more anonymous and secure. Apparently, at least in China,

r a train and someone passed through begging for change. I’ve lived in New York City long enough that I don’t just start taking my wallet out and going through it in crowded public spaces, but beyond that, I don’t have change. I normally don’t carry cash. If I have cash on me its for one of two reasons, either someone has paid me back for something in cash (which in these days of Venmo is increasingly unlikely) or I have a hair or nail appointment where they like their tips in cash. So even if I have cash, it’s bigger bills and certainly no coins. And I’m sure I’m not unusual. I pay for things with credit cards. I pay other people using Apple Pay or Venmo. I mentioned this thought to someone who told me that they had seen someone begging in New York with details of their Venmo account. On the one hand, there seems to be a certain chutzpah to that, after all, if you have a bank account to receive the money in and some kind of smart phone to access it, is your situation as dire as you’re making out? On the other hand, it’s pretty smart. Of course, there are serious privacy issues involved in giving money to a random stranger through an app like Venmo, it’s not private, so I probably wouldn’t do that either, but it’s an interesting idea, if it could be made more anonymous and secure. Apparently, at least in China,

It has been a little over a week since the redacted Mueller Report was released, and so many words have been spilled that there could be a drought by summer if the umbrage reservoirs are not refilled. Can we just retire the word “closure”?

It has been a little over a week since the redacted Mueller Report was released, and so many words have been spilled that there could be a drought by summer if the umbrage reservoirs are not refilled. Can we just retire the word “closure”?

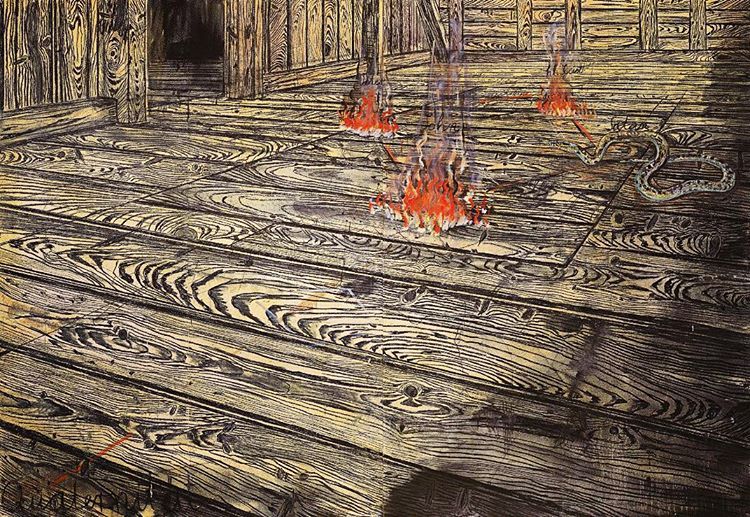

The attic of Notre Dame cathedral, with its tangled, centuries-old dark wooden beams, was affectionately known as the ‘forest’. The fire that originated up there last week made me think of an early Anselm Kiefer painting Quaternity, (1973), three small fires burning on the floor of a wooden attic and a snake writhing toward them, vestiges of the artist’s Catholic upbringing in the form of the Father, the Son, the Holy Ghost and the Devil. Metaphor meets reality in the sacred attics of stored mythologies.

The attic of Notre Dame cathedral, with its tangled, centuries-old dark wooden beams, was affectionately known as the ‘forest’. The fire that originated up there last week made me think of an early Anselm Kiefer painting Quaternity, (1973), three small fires burning on the floor of a wooden attic and a snake writhing toward them, vestiges of the artist’s Catholic upbringing in the form of the Father, the Son, the Holy Ghost and the Devil. Metaphor meets reality in the sacred attics of stored mythologies.

Last time

Last time It’s rather like changing fonts. Not many would say a change of font will make a parking ticket sting less (although Comic Sans might make it sting more). As endless internet discussions rage about the meaning and content of the Mueller report, altogether too few dissect Robert Mueller’s choice of fonts [1].

It’s rather like changing fonts. Not many would say a change of font will make a parking ticket sting less (although Comic Sans might make it sting more). As endless internet discussions rage about the meaning and content of the Mueller report, altogether too few dissect Robert Mueller’s choice of fonts [1]. A brief scan across global politics generates concerns as to what is actually going on in the politics of many states. Authoritarian regimes have always been with us, and will probably be with us for some time to come. Of greater concern is the emergence of political leaders in liberal democracies who espouse a politics which resonates with the past: a politics of nationalism, and nativism, and the inward-looking thinking that is associated with those ideologies. This trend, in what I would call a ‘regressive politics’, is in opposition to the process of globalisation.

A brief scan across global politics generates concerns as to what is actually going on in the politics of many states. Authoritarian regimes have always been with us, and will probably be with us for some time to come. Of greater concern is the emergence of political leaders in liberal democracies who espouse a politics which resonates with the past: a politics of nationalism, and nativism, and the inward-looking thinking that is associated with those ideologies. This trend, in what I would call a ‘regressive politics’, is in opposition to the process of globalisation.

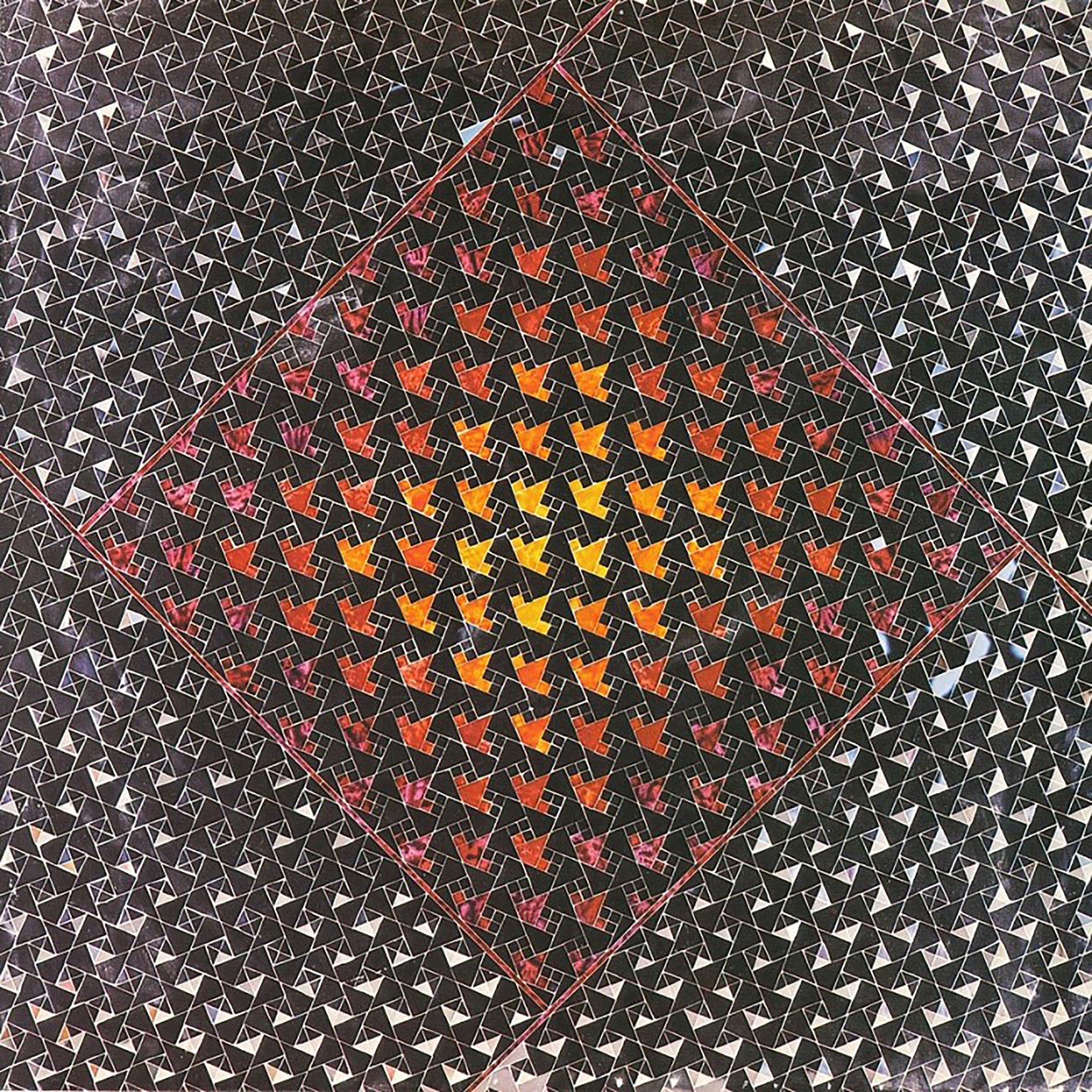

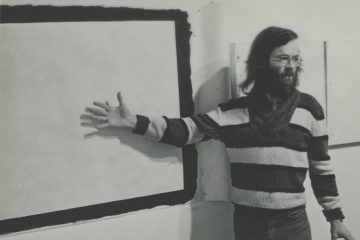

Tony Conrad’s retrospective of objects produced for galleries or institutions, titled Introducing Tony Conrad, is currently on view at the ICA Philadelphia. “Introducing” because so many people are still unfamiliar with his work. His works were predicated on both the amount of time they took to make and the patience that they required of their audience, which no doubt contributed to his lack of popularity. Conrad, the prodigal Harvard grad, spent his career working through aesthetic problems like an eccentric scientist. This can be gathered from his exhaustive lectures, teaching, and writings on sound and film. Formally, however, the works often look like a child made them. Not in a cynical way denoting lack of care, but in an earnestly amateur approach to object making. Because the works are less concerned with looking skillfully produced and more concerned with what a durational existence might impart onto things, the audience is left with big-picture questions like, what does it mean for an artwork to still be in progress after the artist’s death?

Tony Conrad’s retrospective of objects produced for galleries or institutions, titled Introducing Tony Conrad, is currently on view at the ICA Philadelphia. “Introducing” because so many people are still unfamiliar with his work. His works were predicated on both the amount of time they took to make and the patience that they required of their audience, which no doubt contributed to his lack of popularity. Conrad, the prodigal Harvard grad, spent his career working through aesthetic problems like an eccentric scientist. This can be gathered from his exhaustive lectures, teaching, and writings on sound and film. Formally, however, the works often look like a child made them. Not in a cynical way denoting lack of care, but in an earnestly amateur approach to object making. Because the works are less concerned with looking skillfully produced and more concerned with what a durational existence might impart onto things, the audience is left with big-picture questions like, what does it mean for an artwork to still be in progress after the artist’s death? This is best captured in Conrad’s most well-known artworks, the “infinite duration” Yellow Movies, which were painted yellow squares on paper. The idea was that they would darken and yellow with age over the course of their lifespan, thus constituting an ever-changing work, or “movie” (and for Conrad, the longest durational movie ever, putting Warhol’s Empire (1964) to shame). These works and others in the show capture his fascination with time and what it entails. The objects on view in the retrospective are largely the byproducts of experiments. Conrad, an accomplished experimental musician and filmmaker known for his vexing compositions, took his cue from thorough research into a topic, investigating the variety of forms it could take. For instance, one of the first things visitors see are a selection of handmade instruments using unorthodox materials, like a guitar made from a child’s racquet, or violin affixed to a stationary scrap-wood apparatus. Another instance is Conrad’s pickled film, which he shot and then cured in a vinegar solution in Ball jars, riffing on how film is developed in an alchemical solution.

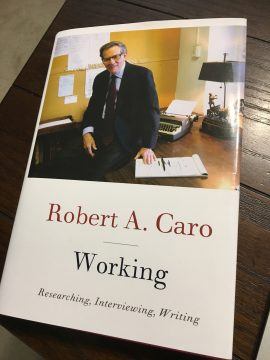

This is best captured in Conrad’s most well-known artworks, the “infinite duration” Yellow Movies, which were painted yellow squares on paper. The idea was that they would darken and yellow with age over the course of their lifespan, thus constituting an ever-changing work, or “movie” (and for Conrad, the longest durational movie ever, putting Warhol’s Empire (1964) to shame). These works and others in the show capture his fascination with time and what it entails. The objects on view in the retrospective are largely the byproducts of experiments. Conrad, an accomplished experimental musician and filmmaker known for his vexing compositions, took his cue from thorough research into a topic, investigating the variety of forms it could take. For instance, one of the first things visitors see are a selection of handmade instruments using unorthodox materials, like a guitar made from a child’s racquet, or violin affixed to a stationary scrap-wood apparatus. Another instance is Conrad’s pickled film, which he shot and then cured in a vinegar solution in Ball jars, riffing on how film is developed in an alchemical solution.  Robert Caro might well go down in history as the greatest American biographer of all time. Through two monumental biographies, one of Robert Moses – perhaps the most powerful man in New York City’s history – and the other an epic multivolume treatment of the life and times of Lyndon Johnson – perhaps the president who wielded the greatest political power of any in American history – Caro has illuminated what power and especially political power is all about, and the lengths men will go to acquire and hold on to it. Part deep psychological profiles, part grand portraits of their times, Caro has made the men and the places and times indelible. His treatment of individuals, while as complete as any that can be found, is in some sense only a lens through which one understands the world at large, but because he is such an uncontested master of his trade, he makes the man indistinguishable from the time and place, so that understanding Robert Moses through “The Power Broker” effectively means understanding New York City in the first half of the 20th century, and understanding Lyndon Johnson through “The Years of Lyndon Johnson” effectively means understanding America in the mid 20th century.

Robert Caro might well go down in history as the greatest American biographer of all time. Through two monumental biographies, one of Robert Moses – perhaps the most powerful man in New York City’s history – and the other an epic multivolume treatment of the life and times of Lyndon Johnson – perhaps the president who wielded the greatest political power of any in American history – Caro has illuminated what power and especially political power is all about, and the lengths men will go to acquire and hold on to it. Part deep psychological profiles, part grand portraits of their times, Caro has made the men and the places and times indelible. His treatment of individuals, while as complete as any that can be found, is in some sense only a lens through which one understands the world at large, but because he is such an uncontested master of his trade, he makes the man indistinguishable from the time and place, so that understanding Robert Moses through “The Power Broker” effectively means understanding New York City in the first half of the 20th century, and understanding Lyndon Johnson through “The Years of Lyndon Johnson” effectively means understanding America in the mid 20th century.