Seder-Masochism, the whole film

Nina Paley recently finished her second feature film, Seder-Masochism. Her first, of course, is the award-winning Sita Sings the Blues, a retelling of the Ramayana from a feminist point of view which Paley released in full in 2008. However, she had started posting segments to the internet several years before that and she has done the same with Seder-Masochism, in which she retells events from Book of Exodus. She began posting segments in 2012 and completed the film last year, when she began showing it at festivals. Paley placed the whole film in general release at the end of January this year.

In both cases Paley has worked outside the mainstream movie industry, perform the tasks writing, directing and animating the films herself.

I want to offer some brief comments about two segments of the film. This Land is Mine is the first segment she released, but it is the last one in the completed film. God-Mother is one of the last she released–I don’t know whether or not it is THE last–but will be the first one in the film, even before the credits. Jordan Peterson has interviewed her and, in that interview, Nina said that the process of making the making turned about to be a journey of discovery in which she, in effect, discovered God-Mother.

Paley created This Land is Mine is in the style she used for the music clips of Sita Sings the Blues:

This Land is Mine

The song is the theme song from Exodus, a contemporary epic about the founding of the modern state of Israel that came out made in 1960. The movie was a hit and so was it’s theme song. Originally an instrumental, “This Land is Mine” was given lyrics by Pat Boone and was a major hit, both in instrumental and vocal versions. Paley’s clip is based on a vocal version sung by Andy Williams.

The segment’s opening is very ‘stagy’:

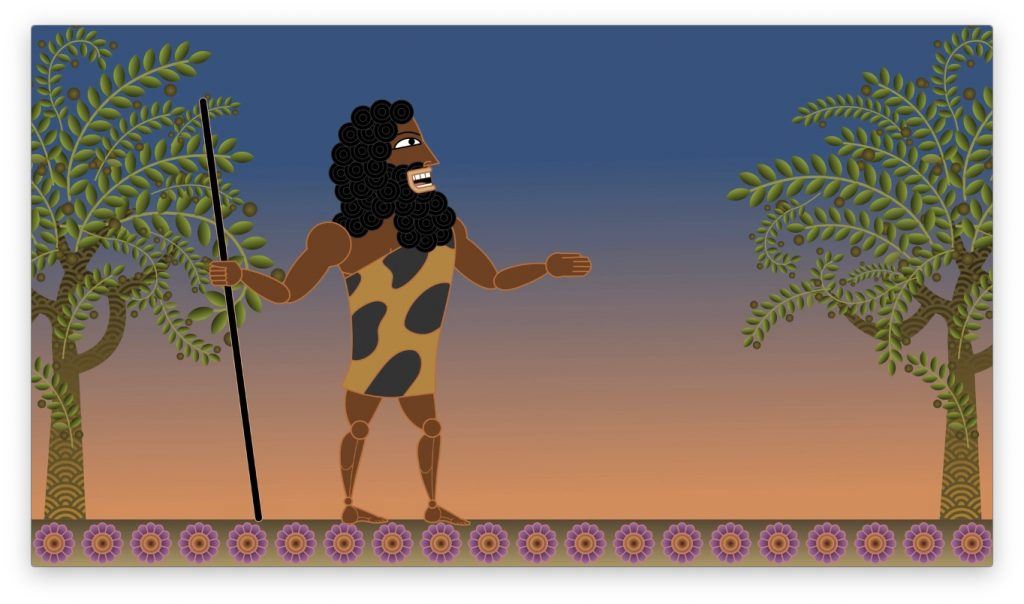

The virtual camera then zooms in on a generic Early Man who starts singing the song:

The camera then stays focused on that space through the clip to the very end.

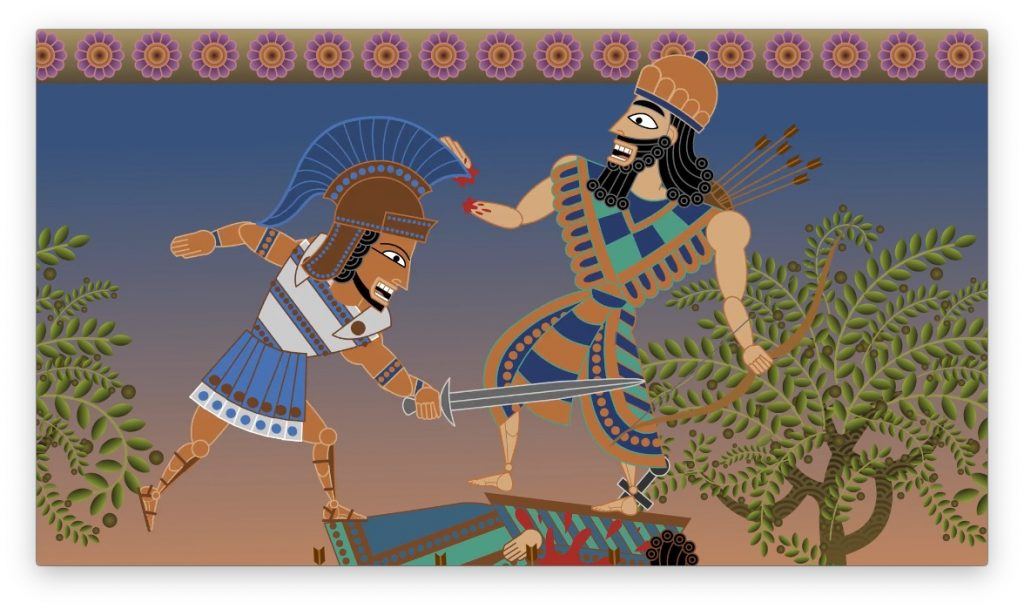

Soon another figure, a Canaanite, enters from the right, in different dress, kills our Early Man, and continues singing. An Egyptian enters from the left, shoots this character with an arrow, and continues the serenade. You can pretty much guess what happens next. Someone enters from the right, kills our Egyptian, and continues singing. Sorta’. Enter from the right, yes. Kills the Egyptian, yes. Continues to sing – you bet. But he passes across the screen, in silhouette, exits at the left, and then re-enters from the left, and comes up behind the Egyptian. Then he kills him. And the slaughter continues, left, right, left, right, etc. until the very end, when we’re all dead:

The atomic Angel of Death takes us all.

This is a very grim segment. Cruel. But also witty, and even beautiful, as Jordan Peterson notes in one of his remarks to Nina.

Paley keeps our interest by changing the costumes of the killers (Paley identifies them all in this blog post) and by varying the timing and method of slaughter. For example, if you know the song at all, then you know at one point we have this line: “So take my hand…” When you hear some poor soul (well, perhaps not so poor, it’s Andy Williams) start singing that, you know what’s going to happen, don’t you?

And so it goes, as Kurt Vonnegut would say. In line after line of this preposterous anthem, people get slaughtered right and left, left and right until the Angel of Death takes them all. Then Paley runs the end credits, but over distinctly different music, a gently swinging version of the theme by Quincy Jones. This last section isn’t used for the complete film, which must accommodate credits for the whole film.

The Beginning: God-Mother

God-Mother

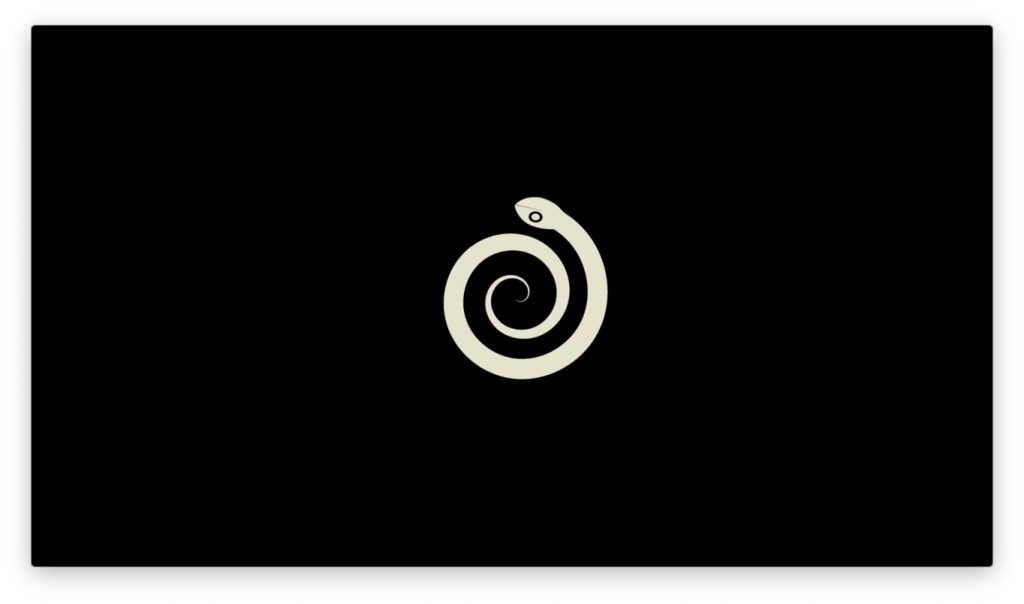

The film’s opening segment, God-Mother, is very different. Paley says that it’s the slowest thing she’s ever animated. It’s also got a completely different visual style, very austere and abstract, and the music is world’s away from Ernest Gold’s theme from the 1960 film, Exodus (with lyrics later added by Pat Boone). Here’s a frame from very very early in the segment:

The snake–or should I call it a serpent?–started as a dot and then spiraled larger and larger and then…I’m not going to try to describe what happens. It’s difficult to describe and easy enough to watch.

Here’s where we are, a bit later:

The snake’s still there. But so is a woman, albeit a very abstract woman. And behind her we have a photo of a starry sky – perhaps a NASA image? All three will continue as motifs throughout the film.

Now the sun/moon/earth enters:

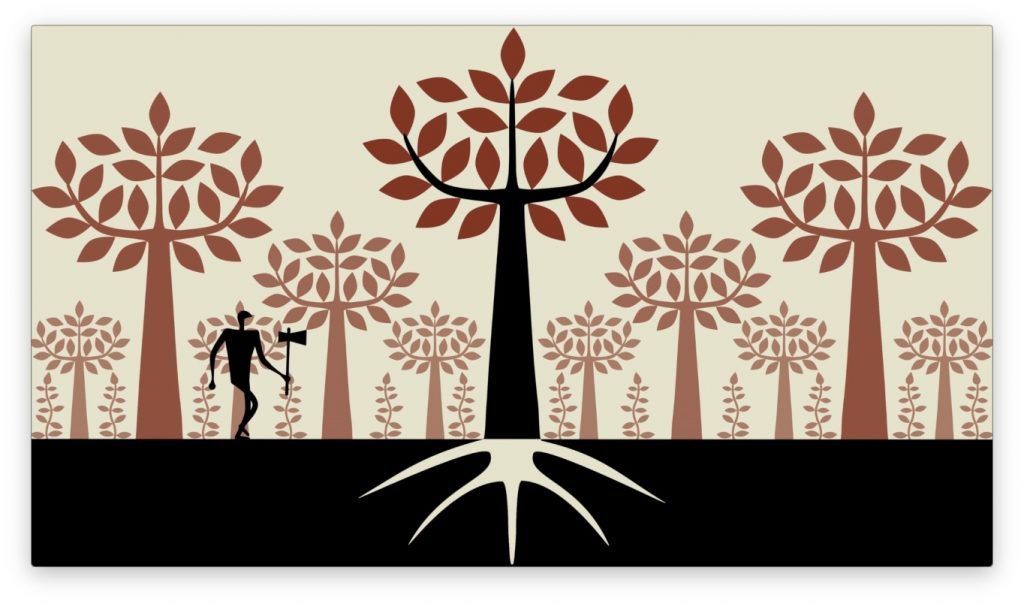

With the addition of that reddish brown we now have the full palette for this segment. As I said, very austere and quite a contrast from the palette of This Land Is Mine and, for that matter, most segments of the film.

There are other motifs, circles and crosses, fish, deer, horses, plants of various kinds. The woman at the middle of this frame is obviously based on an ancient, very ancient stone carving:

Paley’s put many such images in this segment, and photographs of those carvings figure prominent in other segments of the film. Those handprints? I’d guess that they’re based on the handprints one finds in rock art all over the world.

And now we’re near the end:

That large tree in the center? It emerged from the woman in the previous frame through a series of smooth transformations; her feet become roots, her arms and head become branches and leaves. There’s a lot of morphing in this segment. That angular little guy on the left with an ax? You can guess what he’s going to do, can’t you.

Not a happy ending.

The music in this segment is very different from the anthemic “This Land is Mine.” It’s slow, stately, chant-like, performed by the Bulgarian State Radio and Television Female Vocal Choir.

Superficially, different, deeply very much alike

It’s difficult to imagine such very different film segments as these two. The music is utterly different–symphony orchestra and male soloist vs. a female choir (with solo voice or voices)–as is the visual material–full color, rapid action, complex imagery vs. a very restrained palate, slow action, simple images. And yet, abstractly considered, they’re alike.

It’s a bit difficult to conceptualize properly, but both segments depend on the timing of a relatively small repertoire of images. Sure, the cast of characters in This Land is Mine is relatively large, but the range of things they do is quite small. They sing, they kill, and they get killed. That’s it. We know what’s going on, all the time. There’s no mystery about that. We just don’t know exactly when and how it’s going to happen.

God-Mother is similar. The range of imagery is small, though not predictable. Still, once it gets moving you pretty much know that Paley is working variations on a small ensemble of motifs. The action is relatively smooth and the change from one moment to the next is relatively small. But at some point it changes; the rabbit becomes a duck, the old woman becomes young. Exactly when is it going to happen? That’s what Paley has us guessing about.

Sure, movies are about that, movement. And, yes, there are surprises. But in both of these segments Paley brings the movement and the surprises into the foreground, yet without being self-consciously arch or ‘meta’. She brings us an awareness of change and of time as phenomena unto themselves.

Have I got that right?