Photo of moon with a jet vapor trail taken from my balcony in April of 2015.

Photo of moon with a jet vapor trail taken from my balcony in April of 2015.

by Carol A Westbrook

“Medicare for All” is a battle cry for the upcoming national elections, as voters’ health care costs continue to skyrocket. Universal Medicare, they believe, will provide free health care, improve access to the best doctors, and lower the cost of prescription drugs. Is it a dream, or is it a nightmare?

I am 100% in favor of universal health care, but believe me, it ain’t gonna be free. True, I’m not an economist–I’m a doctor–but I can do the math. I’ve had years of experience, both practicing under Medicare’s system and as a Medicare patient, and I understand something about health care costs. Few voters under age 65 understand what Medicare provides, and even fewer have a grasp on what it will cost the government–and ultimately the taxpayer–to extend it to all.

What Medicare provides for free is Medicare A insurance, which covers inpatient hospital, costs. To cover outpatient and emergency room visits, the senior must purchase Part B, which covers 80% of these charges. Medicare B costs $135/month plus a sliding scale based on income. Prescription drug coverage requires purchasing Medicare D from a private company. (Medicare C is alternative private insurance). Medicare A, B and D premiums are all deducted from the monthly Social Security check. Additionally, a senior may purchase a Medicare Supplement from a private insurance company, which covers the un-reimbursed Part A, and B costs. Confusing? Here are two examples. Read more »

by Gabrielle C. Durham

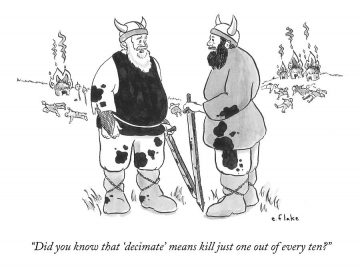

If you took Latin, then you probably have a larger vocabulary than the average bear, and you are more likely to have strong opinions on some words you vaguely remember based on Latin roots (cognates). For example, folks are more commonly using “decimate” to mean destroy or devastate, and it annoys the living materia feculis out of me. Decimate originally meant to kill every 10th person, based on the Latin word for 10 (decem), which is so oddly and satisfyingly specific. “Devastate” and “destroy” are already well known and used, so why do they need another alliterative ally in little weirdo “decimate”?

If you took Latin, then you probably have a larger vocabulary than the average bear, and you are more likely to have strong opinions on some words you vaguely remember based on Latin roots (cognates). For example, folks are more commonly using “decimate” to mean destroy or devastate, and it annoys the living materia feculis out of me. Decimate originally meant to kill every 10th person, based on the Latin word for 10 (decem), which is so oddly and satisfyingly specific. “Devastate” and “destroy” are already well known and used, so why do they need another alliterative ally in little weirdo “decimate”?

Another little sneak is “cleave.” Meaning #1 is to adhere tightly and closely or unwaveringly. Meaning #2 is to divide or split, to separate, or to penetrate a material by or as if by cutting or tearing. The second meaning is where we get “cloven” as in “cloven hoof,” the tool “cleaver,” “cleft” as in “cleft palate,” and “cleavage.” Both versions arose before the 12th century. The first meaning comes from Old English clifian by way of Middle English clevien. The second meaning comes from Middle English cleven from Old English cleofan and likely Old Norse kljufa, meaning to split. How can these words be so close for almost a millennium with polar opposite meanings? Read more »

by Abigail Akavia

Two weeks ago I celebrated Passover with my family. It was an intimate affair, just four adults and three preschoolers in the small dining room of our rented apartment in Leipzig. Our secular way of life makes Passover, for us, a holiday of light-to-non-existent religious content; nonetheless the richness of the symbolism and of the ritualistic foods is still something we enjoy. Making the Seder palatable to the kids, both the dinner itself and its ritualistic elements, became the central concern for us, their perpetually exhausted parents. The traditional text read in the Seder, the Haggadah, is cryptic in its Aramaic expressions and passages of Talmudic hermeneutics, on which the guests, both young and old, are encouraged to ask questions. But our distaste for the way the myth of Passover resonates in contemporary nationalistic discourse in Israel and elsewhere has brought us to include alternative content in our Seders, stories of other historical struggles towards freedom, which have often been conceived in terms that echo the story of Exodus. This year we read parts of the Hagaddah composed by Rabbis for Human Rights, which was originally read in a detention camp for African refugees in the Israeli desert in 2016, and includes Bob Marley’s Redemption Song. When we lived in Chicago, we told stories of Harriet Tubman and The Underground Railroad.

An Israeli Seder is not dissimilar to American Thanksgiving: a long meal that commemorates the founding of the nation, along with the post-nationalistic reckoning that both holidays can prompt. In both cases, a religious-historical myth becomes incarnated in food. Thus, the matzo, the most important culinary feature of Passover, reminds us of the unleavened bread that the Israelites hastily prepared when they fled their enslaving Egyptians. Every other part of the meal is also meant to symbolize part of the story, that of the Hebrews’ struggle to become a nation. (The series of hardships which the Seder is meant to recall may explain why the Seder meal, while as excessive as a Thanksgiving dinner, is arguably less delicious.) Read more »

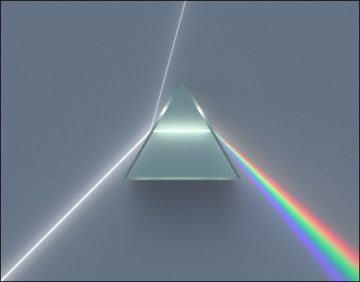

in the matrix of a prism is magic

of two kinds, the inestimable

and that which can be counted

—the inestimable cannot be counted

by definition

if I say red is passionate hot sexy

or if I say red’s the color of death

in unstoppable bleeding

or that its fresh blush reminds me

of one spectacular sunrise

or the touch of you

there’s no calculation I can make

that will sum red’s isness because

as it comes by refraction

from the nothing of white

it may enter a zone

of the most inexplicable

part of mind which is always

putting its private spin on things

but

if I say red’s frequency is 4.3 times

ten to the fourteenth hertz

I’ve dropped into the estimable

spectrum of words which

…….. when so precisely split

leave’s no room for imagination

which just makes me blue

Jim Culleny

4/30/19

by Shawn Crawford

In 1904 America, of boys between the ages of ten to fifteen, 26% worked full time away from home. In the textile mills of New England, children began working at age six for twelve to sixteen hour shifts. When dozing off, cold water would be thrown on them. Ingrates. At the turn of the twentieth century, 70% of children working as migrant pickers in Colorado’s fields had become deformed from the labor.

Given the horrendous conditions, one would think child labor laws sped their way through congress at the beginning of the twentieth century. Instead, a decades-long battle saw legislators bellowing for the rights of business owners and decrying the laziness of the American worker. Chief among these was Weldon Heyburn, an Idaho senator and Theodore Roosevelt’s nemesis. Heyburn thought anyone, including children, that didn’t work from sunup to sundown an idler. And the rights of the business owner had to remain sacred; if someone wanted to hire a fetus to dig coal then by god the government had to protect that right. One can only assume today’s health-care debate would have caused Heyburn’s head to explode.

But after the hysteria and grandstanding and rhetoric died down, sensible child labor laws became established, including the complete banning of children from certain occupations. The pace of industrialization simply outran most people’s understanding of what children could safely do, and as always certain ruthless businesses were happy to exploit the situation. Besides which, the idea of childhood as a distinct time of development separate from adulthood remained a new and contentious idea. For years, children existed as miniature adults, and the faster they took up the work and learned the realities of the adult world the better. Both culture and science would come to understand children as different from adults on all levels: emotionally, physically, and psychologically.

But as we usually do, Americans have forgotten their past and proved incapable of applying former lessons to new contexts. Because while we protect children from labor and most other unpleasant adult responsibilities, we have no problem unleashing them to run free in all the perks of adulthood. Read more »

by Samia Altaf

Soon after President Obama moved into the White House, Mrs. Obama set up her vegetable garden. She planted tubers like carrots and turnips, leafy veggies such as spinach and kale, and herbs—thyme, sage, mint, and whatnot. But she did not plant beets. Why? I was quite perplexed and tried to find out the reason. I called the White House but did not get a satisfactory answer. “What the hell are you talking about?” said someone who picked up the phone. Maybe her children do not like them, said my child who was not overly fond of the vegetable. Not like beets? How is that possible? Of all the tuberous veggies available to man, the beet in my view is one of the best and the most poetic.

Soon after President Obama moved into the White House, Mrs. Obama set up her vegetable garden. She planted tubers like carrots and turnips, leafy veggies such as spinach and kale, and herbs—thyme, sage, mint, and whatnot. But she did not plant beets. Why? I was quite perplexed and tried to find out the reason. I called the White House but did not get a satisfactory answer. “What the hell are you talking about?” said someone who picked up the phone. Maybe her children do not like them, said my child who was not overly fond of the vegetable. Not like beets? How is that possible? Of all the tuberous veggies available to man, the beet in my view is one of the best and the most poetic.

I, too, as a rebellious ten-year-old, did not quite like beets. Well, I liked them all right, I just did not like to eat them. I liked looking at them laid out with the dirt still clinging to the quivering roots. And the color! The color, that deep dark red verging on purple, intrigued me. In Urdu poetry, the idiom khoon-e-jigar is central. Though the literal translation (“blood of the liver”) is both prosaic and meaningless, it leaves the Urdu poetry buff aswirl with the despair of true or imagined loss mixed with the exquisitely tender pain of thwarted desire. The color of beets would be the color of that pain. If the liver bled that would be the color of its blood, as I confirmed during surgical training when I saw blood in the hepatic vein. So, whenever I heard Ghalib’s immortal line dil ka kya rang karoon khoon-e-jigar hone tak I’d think of beets and feel that the great nineteenth-century poet was thinking of them too. Concentric circles of dark and darker still, altogether a swirl of vivid colors and smoldering passions and black brooding juxtaposed against the colors of the leaves, the dull green of the old on the outside and the fresher lighter tone of the new, tender and vulnerable on the inside. I loved cutting a beet in two, looking tentatively inside, and rubbing it on my lips till grandmother gave me hell. My mother, who had much disdain for new-fangled cosmetics like lipsticks, said that brides in her time rubbed bleeding beets on their lips, a practice that was strictly prohibited for the unmarried.

I loved beets. I just did not like to eat them. Read more »

by Brooks Riley

by Joseph Shieber

In our pluralistic society, could First Amendment protections of religious freedom, say, clash with other firmly entrenched legal norms? So, to take a particular example, suppose a Muslim woman was called as a prosecution witness in a criminal trial. Could her religious obligation to wear the niqab trump the defendant’s right to confront his accuser?

I began thinking about this particular sort of case because of a September 2018 decision in the Pennsylvania murder trial of Tyreese Copper, who was convicted and sentenced to life in prison. One of the witnesses for the prosecution was a Muslim woman named Davina Sparks, who insisted upon being allowed to wear the veil covering her face while giving testimony in open court.

Here’s what happened next, according to the account at the Volokh Conspiracy blog. The defendant’s attorney

objected to Ms. Sparks testifying while wearing her Muslim garb that covered her face. Ms. Sparks refused to remove the garb, citing her religion as the reason for her refusal. Out of deference to Ms. Sparks’s religious beliefs, the court decided to clear the courtroom for Ms. Sparks to testify without her face garb “so I can at least have her taking off her covering only in the presence of the people who are absolutely essential to being here,” i.e. the jury, court staff, defense counsel, and defendant.

Now, as Volokh goes on to discuss in his post, Commonwealth v. Copper has become an object of debate because the judge’s clearing the courtroom impinged upon Copper’s Sixth Amendment right to a public trial (via the Fourteenth Amendment). But I want to look at the case from a different perspective. Read more »

I’m trying to get down the light:

smooth-pooling & blue midday

a touch of peach and green

rising off the street at night

& casting against my face.

I try to get the light into my body

so it won’t leave me

I swallow everything glowing:

it started with leaves hanging

coated with a dazzling frost

then I started chewing

water glasses, I enjoyed the crunch–

then lit cigarettes flicked from fingers

thick sludge gleaming in gutters

(I bring my own cup)

and artificial emeralds

ripped from a passing stranger’s neck.

by Tamuira Reid

Nadia was missing. She had been missing for three days. Three days, two hours, six minutes. Each time a pair of feet clunked up the stairs, a set of keys jangled, someone coughed, laughed, sighed, or took a piss I’d push the door open a crack, still bolted, because it’s New York, because I am conditioned into doing these things. I’d peer into the long hallway, searching for her face only to come up empty.

****

We officially met in the middle of the night, after a failed attempt at baking on my end. I was standing on a chair, half-naked, using a throw pillow to fan the air around the smoke detector. Ollie cried from the bedroom.

Are we on fire?

It’s okay, baby. Nothing is on fire.

There was knocking at the door. A pounding at the door. I jumped off the chair and put a jacket on.

It’s the firemen, mama! Did they bring a dog?

I stared through the peephole and saw the big blonde Russian from next door. She moved in a month before, right after the drummer moved out. She was a lot quieter than him and wore winged eyeliner and red lipstick and had tattoos wrapped around her neck like scarves. Sometimes I’d see her at night, when I’d climb out onto the fire escape and smoke a guilty cigarette after my boy had fallen asleep, stretched across the width of our bed. She was out there smoking too, hips bumping against the metal rail, looking up at a starless sky.

Can I help you?

Shut that shit off.

I’m trying.

Let me in. I’ll do it.

I pulled my jacket tighter around me. She was even taller than I remembered, and somehow prettier. In a matter of seconds, she pushed past me, grabbed an umbrella from its hook on the wall, and gutted the detector with one swift swing. Silence.

It was love at first sight. Who cared if I was straight. I’d make it work somehow. Read more »

by Emrys Westacott

Recently, I was waiting to board an American Airlines flight from Boston to Rochester, when, along with ten of my fellow passengers, I was summoned to the desk in front of the boarding gate. There we learned, by listening intently to what the AA gate agent told the first passenger in line, that we were being bumped from the flight, that AA would try to find alternative flights for us, and that we would each receive a voucher worth $250, redeemable on AA bookings, valid for one year.

Recently, I was waiting to board an American Airlines flight from Boston to Rochester, when, along with ten of my fellow passengers, I was summoned to the desk in front of the boarding gate. There we learned, by listening intently to what the AA gate agent told the first passenger in line, that we were being bumped from the flight, that AA would try to find alternative flights for us, and that we would each receive a voucher worth $250, redeemable on AA bookings, valid for one year.

Of the eleven victims, reactions were mixed. Most of us chunteringly but passively accepted our fate. But two or three individuals kicked up nasty. One woman smacked her hand on the counter in front of the agent and declared loudly, “Listen. I’m not interested in your excuses. I am getting on that plane!” A tall man with an incredulous sneer fixed on his face continually informed both the AA agents and the rest of us for the next half hour that the reason they were giving for why we had to be bumped was “bullshit, pure bullshit.”

He seemed to have a point. The reason provided for why we were being bumped was that, given its required fuel load, this particular plane would be too heavy with us on board. I’m not sure how many passengers actually boarded the plane, but I would guess it was fewer than sixty; so the ratio of bumped to boarded seemed remarkably high. We all assumed that AA had simply overbooked the flight, as airlines regularly do in order to make more money, and the agents were following a script which involved feeding us a bogus justification. “Safety regulations require that…..” is always going to sound more acceptable than “Our concern to maximize profits has led us to….”

Asked how they chose whom to bump, the supervising agent said the selection was based on who had checked in last. This, too, seemed dubious since some of us had checked in online the night before. He didn’t mention the fact that bumpees were chosen exclusively from the cheap seats, although this is standard practice.

Still, every cloud, etc. Observing the behaviour of the outraged and vocal bumpees, provided an occasion for reflection on the ethics of dealing with bureaucracy when one feels one is being in some way wronged or treated badly.

First, we need to make a basic distinction between (a) a jobsworth, and (b) institutional bullshit. Read more »

by Dwight Furrow

Wine writers often observe that wine lovers today live in a world of unprecedented quality. What they usually mean by such claims is that advances in wine science and technology have made it possible to mass produce clean, consistent, flavorful wines at reasonable prices without the shoddy production practices and sharp bottle or vintage variations of the past.

Wine writers often observe that wine lovers today live in a world of unprecedented quality. What they usually mean by such claims is that advances in wine science and technology have made it possible to mass produce clean, consistent, flavorful wines at reasonable prices without the shoddy production practices and sharp bottle or vintage variations of the past.

This general improvement in wine quality is to be welcomed but I would argue that for wine aesthetics a more important development is the unprecedented diversity in our wine choices. What wine writer Jon on Bonné, recently referred to as “weird wine”—natural wine, orange wine, wine in cans, wine from unfamiliar locations—is an important part of the wine conversation. Wine is now made in every state in the U.S. and most of those states have their own indigenous wine cultures with distinctive varietals and unique terroirs. Throughout the world, emerging new wine regions from Great Britain to China promise to add to the stock of diverse tasting experiences. Wine grapes are increasingly grown in extreme environments—from high in the Andes, to the deserts of the Golan Heights, to the chill lake sides of Canada. Projects such as Vox Vineyards in Kansas City, Bodegas Torres in Spain, and Bonny Doon in Santa Cruz, California are rediscovering lost or ignored varietals while the University of Minnesota develops new varietals that can survive Northern winters. If you’re willing to navigate our spotty distribution system, most of this diversity is widely available. Although the best wines from the storied vineyards of France are now available only to the super wealthy, new generations of wine drinkers are growing tired of the hamster wheel of Cabernet/Chardonnay/Merlot and are seeking something more adventurous.

This focus on variation has not always been an intrinsic part of wine culture. As I described in my column last month, in the early 1990’s the growing wine culture in the U.S. was dominated by trends that would tend to increase homogeneity. Excessive ripeness, a reductionist approach to wine science, overly narrow critical standards, and most importantly rapid growth in the wine industry were poised to transform wine into a standardized commodity like orange juice and milk, serving a function but without much aesthetic appeal.

So what happened? How did we avoid that monotonous landscape of homogeneous juice? Read more »

by Dave Maier

“Realism” is a word with many senses. In politics, it’s synonymous with pragmatism in being the alternative to idealism, which it considers naive. In science, realists oppose instrumentalism and (extreme forms of) empiricism, positing a reality behind the phenomena of empirical investigation. In philosophy as well, one can be a realist about this or that by resisting the reduction of that or this phenomenon to other things thought more ontologically basic.

Mainly, though, philosophical realism is metaphysical realism, an ontological commitment to a basic reality irreducible to, and independent of, mind, belief, language, social conventions, empirical observations – whatever you got. On this side of the pond, realism has generally been considered the default position, but analytic philosophy was born in linguistic analysis and a robust strain of empiricism, so various sorts of antirealism have remained popular here as well.

On the Continent, however, things are different. Analytic philosophy was a revolt against a post-Hegelian tradition which remained dominant in Europe, and in the last third of the previous century, when postmodernism ruled supreme, continental realists hardly dared even show their faces in public. At least, that’s the story now being related by a new breed of continental realist. Now that postmodernism is yesterday’s (or last week’s) news, realism is popping up all over.

If postmodernism was nonsense on stilts, then a return to common sense can only be good. But analytic antirealists, at least, aren’t just dimwits or charlatans, and we shouldn’t simply identify substantive philosophical claims, however intuitive, with mere sanity; and continental realism, it turns out, comes in a bewildering variety of forms. Before sounding the hosannas, and awarding the palm to realism at last, we owe this new development a closer look. Read more »

every day I am

in vestment

it’s morning

I dress in

sunskin

cloudskin

earthskin

in the skin

of a universe

though I’ve hoped to slough

them off, to be unveiled

as they’re outgrown,

I’ll always be,

while I’m here, in

vestment

Jim Culleny

4/10/19

by Leanne Ogasawara

Anyone who has ever found themselves caught in a staring contest with an octopus –those soulful cat-eyes returning your gaze through the thick glass of an aquarium tank– can attest to the uncanny power these creatures exert over our human imagination.

They certainly look alien. With three hearts pumping blue, copper-infused blood, their tentacles (“each with a mind of its own”) are covered in suckers that can feel AND taste. Because their beaks are the only hard parts of their bodies, a large octopus can squeeze through a hole not much bigger than one of their eyeballs. They are like the Great Houdinis of the deep! Without a hard shell like other mollusks, octopuses have evolved clever ways for keeping a step ahead of predators: Not only can they change colors to camouflage themselves, blending into almost any watery environment, but they can also send out ink bombs. After lobbing one to confuse an enemy, an octopus can jet propel away from danger at surprising speeds in a funnel of water.

Is it any wonder that there have been people who believe they might have originated in space? From the Scandinavian myth of the Kraken and Jules Vernes’ 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea, to Japanese sea monsters and the sexual predators found in erotic shunga prints, again and again–in so many cultures around the world– these creatures show up in stories and art as monsters and space aliens. And who could forget the fear instilled in the losing soccer teams by Paul the Clairvoyant World Cup Octopus? The Argentines got so angry at him that they threatened to kill him and cook him in a paella, if he kept foretelling their bad luck!

My own personal octopus “horror” is the not-as-rare-as–you-would-think sight of Japanese TV personalities (and a few of my friends) traveling in Korea and eating live octopuses–desperate tentacles clawing their way out of the people’s mouths! Read more »

by Robert Fay

During the annus horribilis of 1968 when it became clear the U.S. would never “win” in Vietnam, John Wayne decided to star and direct in a propaganda film called The Green Berets. Wayne was a die-hard Orange County anti-communist who believed that the U.S. military was winning on the battlefield in South Vietnam, but losing in the media and public relations realm.

Rather shrewdly, Wayne centered his film on the U.S. Army Special Forces, a.k.a. the Green Berets, whose small 12-man A-Teams lived and trained with the anti-communist Montagnards, the indigenous peoples of Vietnam’s remote central highlands. The Green Berets in the 1960s were an all-volunteer, highly-selective outfit with both mystique and a bit of holdover, Kennedy-era glamour. These teams spoke the local languages and formed close and often lifelong bonds with their Montagnard peers. This mission profile remains to this day the classic Special Forces game; make contact with local populations and then fight alongside them against a common enemy.

If John Wayne had depicted the typical American military units in Vietnam, main-line U.S. Army or U.S. Marine Corps infantry troops trudging through rice fields—even with all the hilarious puffery of Hollywood special effects—he’d have had far-less glamour to work with. These units were often filled with draftees who went out on company-sized operations supported by massive amounts of artillery and air support, some of it indiscriminately unleashed upon the countryside. There were generally no Vietnamese speakers among the troops, and the cultural and historical knowledge (e.g., of the recent Indochina War between the Vietnamese and the French) was nil. Read more »

by Bill Murray

![]() My wife and I live in the southern Appalachian mountains across a narrow valley from Georgia’s highest mountain. Most of our farm borders the United States Forest Service, pretty far up in the woods. If we don’t go out, we might not see anyone for a week.

My wife and I live in the southern Appalachian mountains across a narrow valley from Georgia’s highest mountain. Most of our farm borders the United States Forest Service, pretty far up in the woods. If we don’t go out, we might not see anyone for a week.

It’s so far up in north Georgia that we shop in North Carolina, which is way more cosmopolitan. In Murphy (population 1638), they have a shop that sells different kinds of cooking oils.

Just 2-1/2 hours north of Atlanta, up in the mountains, isn’t like you might expect in the southern United States. It snows in winter and you usually can’t get a proper grip on spring until the middle of April. Like this year.

Our view to that mountain, called Brasstown Bald, is all natural. From the farm to the peak there’s not a manmade thing to see. The Bald, at 4783 feet, makes its own weather, and ours, too. We wake to its lenticular top hats, revel in its autumn flamboyance and in summer, cower under its electric fury. That requires periodic replacement of our home electronics. Read more »