by Bill Murray

![]() My wife and I live in the southern Appalachian mountains across a narrow valley from Georgia’s highest mountain. Most of our farm borders the United States Forest Service, pretty far up in the woods. If we don’t go out, we might not see anyone for a week.

My wife and I live in the southern Appalachian mountains across a narrow valley from Georgia’s highest mountain. Most of our farm borders the United States Forest Service, pretty far up in the woods. If we don’t go out, we might not see anyone for a week.

It’s so far up in north Georgia that we shop in North Carolina, which is way more cosmopolitan. In Murphy (population 1638), they have a shop that sells different kinds of cooking oils.

Just 2-1/2 hours north of Atlanta, up in the mountains, isn’t like you might expect in the southern United States. It snows in winter and you usually can’t get a proper grip on spring until the middle of April. Like this year.

Our view to that mountain, called Brasstown Bald, is all natural. From the farm to the peak there’s not a manmade thing to see. The Bald, at 4783 feet, makes its own weather, and ours, too. We wake to its lenticular top hats, revel in its autumn flamboyance and in summer, cower under its electric fury. That requires periodic replacement of our home electronics.

In 2017 we hosted our own personal Woodstock of friends who came to see the moon’s shadow scythe through the valley and snuff out the Bald’s glory, it’s whole self, for fifty-seven seconds – a total eclipse.

We drove up to Asheville, North Carolina a few weeks ago and saw all our indigenous animals at the wildlife center there, wolves and wildcats and hellbenders and rattlers and copperheads and foxes and fancifully perhaps, a newly acquired red panda, some relative of whom is said to have lived around here in the distant past.

Living on a farm in the country, precious little changes day to day. Deer hover around the pasture when the horses aren’t grazing. A pileated woodpecker couple have lived alongside us as long as we’ve been here.

That’s the idyllic part. At the same time, every week of our lives we lament the utter lack of big city ethnic food. We go out into the world, come back and make continuing swipes at replicating world food in our kitchen. Pro tip: don’t even bother trying injera.

I write these as valedictory remarks, because we’ve saved and planned and schemed and dreamed and now we’re putting down a big, big marker: this month we are done with daily work forever, if things work out.

This monthly column is called On the Road, and here we go, first with a month in Vietnam and a slow poke around Southeast Asia. Then, the rarified not-too-many weeks when all the Nordic cities empty en mass into summer cottages, saunas and lakes under the birch forests.

•••••

Appalachian folks are my twenty-year tribe, and I’m happy to see the publication of a new, overdue riposte to J.D. Vance’s unctuous Hillbilly Elegy: A Memoir of a Family and Culture in Crisis, an Appalachian memoir that takes to task some of the kindest, most welcoming people in this country.

Mr. Vance wants you to know straight out how, from hardscrabble origins, he followed the financial world’s regnant wealth-acquiring path to its venture capitalist reward, and that the hillbilly people he grew up with can count filth, sloth and lack of couth as reasons they’ll never fill his wing-tips. His book is unkind, personal, and I didn’t much like it. (To be fair, I received some gentle pushback about this on my own site.)

Hillbilly Elegy played straight to the driving, striving, take-no-prisoners careerism of reporters and reviewers (I’m going to speculate few of whom are Appalachian). It reviewed well across the political spectrum.

Now comes a rejoinder from West Virginia University Press in the form of Appalachian Reckoning: A Region Responds to ‘Hillbilly Elegy,’ edited by Anthony Harkins and Meredith McCarroll. Money quote: “Hillbilly Elegy ” is not aimed at [the white working class], but rather at a middle- and upper-class readership more than happy to learn that white American poverty has nothing to do with them or with any structural problems in the American economy and society and everything to do with poor white folks’ inherent vices.” I like to believe that three years on since Hillbilly Elegy’s publication, more and more of us are rethinking the naked wealth-striving that has marked the last several decades.

Appalachia has its challenges, but our part of the country is a beautiful place, full of natural wealth, the type that comes without avarice. If my wife, dogs, cat, horses and I run into a problem here on the farm I’ll trust my neighbors, the retired carpenter, the loggers or the guy who hustles a living with his Bobcat and gravel truck for help long before any proselytizing and disdainful venture capitalist.

•••••

As a very young man, I traveled to the Berlin Wall on New Year’s Eve, 1989, six weeks after its breach, and sat atop that wall beside an East German teenager who had never been across. Incipient change was so apparent that, while H. W. Bush managed down the Cold War and managed unification of Germany in NATO, I became impatient for his New World Order to go ahead and sort out the post Cold War world.

As a very young man, I traveled to the Berlin Wall on New Year’s Eve, 1989, six weeks after its breach, and sat atop that wall beside an East German teenager who had never been across. Incipient change was so apparent that, while H. W. Bush managed down the Cold War and managed unification of Germany in NATO, I became impatient for his New World Order to go ahead and sort out the post Cold War world.

Nothing stuck, for the longest time. Madeleine Albright’s notion of the Indispensable Nation came and went. No particular vision there, just Dutch peacekeepers on a short, dismal leash in Srebrenica.

Dubya’s with-us-or-against-us? How’d that work out? Barack Obama (like H.W.) didn’t do the vision thing, just a press release pivot to Asia, some vague notion about Americans going to live in Darwin. It all took the longest time, 24 years of presidents.

Change happened slowly at first, then all at once. It is important for us to see what is before our eyes today. A faction of Americans is keen to bargain away freedom for security, the country’s highest court has upheld a ban on travel from several predominantly Muslim countries and, as wealth concentration returns to “levels last seen during the Roaring Twenties,” the economist Emmanuel Saez warns “democracies become oligarchies when wealth is too concentrated.”

Acting up politically isn’t strictly the province of the U.S., of course. The Sultan of Brunei has recently endorsed throwing stones at a person until he or she dies from blunt trauma, or stoning, as a method of killing for the offenses of adultery and gay sex.

Let’s all boycott the Sultan’s hotels, sure, but repellent rule flourishes far beyond his sinecure. From the Philippines east and Brazil west a rich bouquet of odium reigns. In Europe Jarosław Kaczyński professes to protect Poles against migrants carrying “all sorts of parasites and protozoa.” Victor Orbán, his country the recipient of virtually no refugees, offers himself as the bulwark against the enemy at the gate.

Still, eyes on the prize. Could the turmoil since the 2015 refugee flow into Europe, itself on the heels of the misery of the Great Recession, be the shove we needed to “an intergenerational shift toward post-materialist values”? NB: the incoming Slovakian President Zuzana Čaputová and the fair, calm election in Ukraine.

•••••

By the time they invented the term “bucket list” our bucket was considerably full. I’ve learned since that bucket list comes from things to do before kicking the bucket, from a 2007 movie.

I didn’t see that movie. We’ve been a little cloistered here on our hill and I was puzzled when suddenly the whole world declared the need to skydive and enter Machu Picchu through the Sun Gate. Around that same time, the brief phenomenon known as the “life coach” advised that we spend our money on experiential vs. material things. Sustainable career path or not, life coaches were onto something there.

My cohort were model consumers. Rising to adulthood in the last third of the 20th century, we wanted what all the ads told us we wanted – and more of it than you had. I am not especially proud that I spent fourteen years playing corporately-chosen music on the radio as a disc-jockey, which used to be a thing. Record labels, whatever in the world those were in retrospect, determined what everyone would listen to.

Payola happened at the managerial level. Mere employees like us got free records and an occasional night out, although at my pay grade, not free cocaine. I never thought much about how I was doing my bit for Columbia Records by driving Whitney Houston to the top of the charts, but now that I think back, promoting Billy Joel and Linda Ronstadt and the others had as much cultural heft as promoting the Kraft Heinz Company these days.

Corporate malfeasance is like the poor; it will always be with us. But why must governmental malfeasance? Why is presiding over a banner era for riches not enough? Why must this administration’s championing of wealth accumulation be so attached to creeping political disfunction, in our close allies’ systems and our own?

• While there may always be an England, this summer the United Kingdom diminishes tragically, by the week, before our eyes.

• An Israeli public relations firm aligned with Likud placed some 1,200 cameras in predominantly Arab polling stations and boasted about how it helped hold Arab voter turnout to historically low levels in the 8 April election.

• Here in Georgia and North Carolina our gentle southern manner is only political caricature. In both states, the party that held the governorship in the last election worked to constrain minority voter participation.

The Georgia Secretary of State crafted a law to make it harder to vote in majority black counties. The black candidate for governor then lost her election – to that same Secretary of State.

A congressional district in North Carolina remains without representation six months past election day because the Republican candidate’s campaign drove around and picked up absentee ballots from voters and filled them in for their side.

Legend has an apprentice weaver in 19th century Leicester destroying knitting frames with a hammer in reaction to the degradations of the new industrial age. The 2020 Luddite is a gig worker. Will she rise against the new authoritarians?

It won’t be easy. Venality has barnacled itself tick-tight to our foundering late-capitalist ship. Accumulated wealth tugs strong as the tides against the inevitable rise of the Green New Dealers.

But it’s coming. You can sense the borning of a movement for renewal, an inchoate striving for inclusion, fairness and equanimity, as sure as you can pick out the sound of a pickup truck on gravel way down our Appalachian driveway.

I reckon my wife and I are leaving the United States in its most fraught condition in fifty years. Maybe this is a good time to slowly put things down, back away and study our country from a distance, for perspective.

But we’ll be back, and ever the optimist, I have reserved a hotel room in Des Moines the week of the Iowa caucuses, hoping they will kick off a blockbuster Democratic primary season. Perhaps by then the process of repairing our country will be underway. Perhaps it already is.

I like this Tana French quote from a 2004 detective novel: “Dublin goes fast, these days, fast and jam-packed and jostling, everyone terrified of being left behind and forcing themselves louder and louder to make sure they don’t disappear.”

That stands up pretty well in the USA fifteen years on.

Louder and louder is tiresome. So here’s what we’ll do for a while: we’ll disappear.

Not from the world. Only from the shouting.

See you next month from on the road.

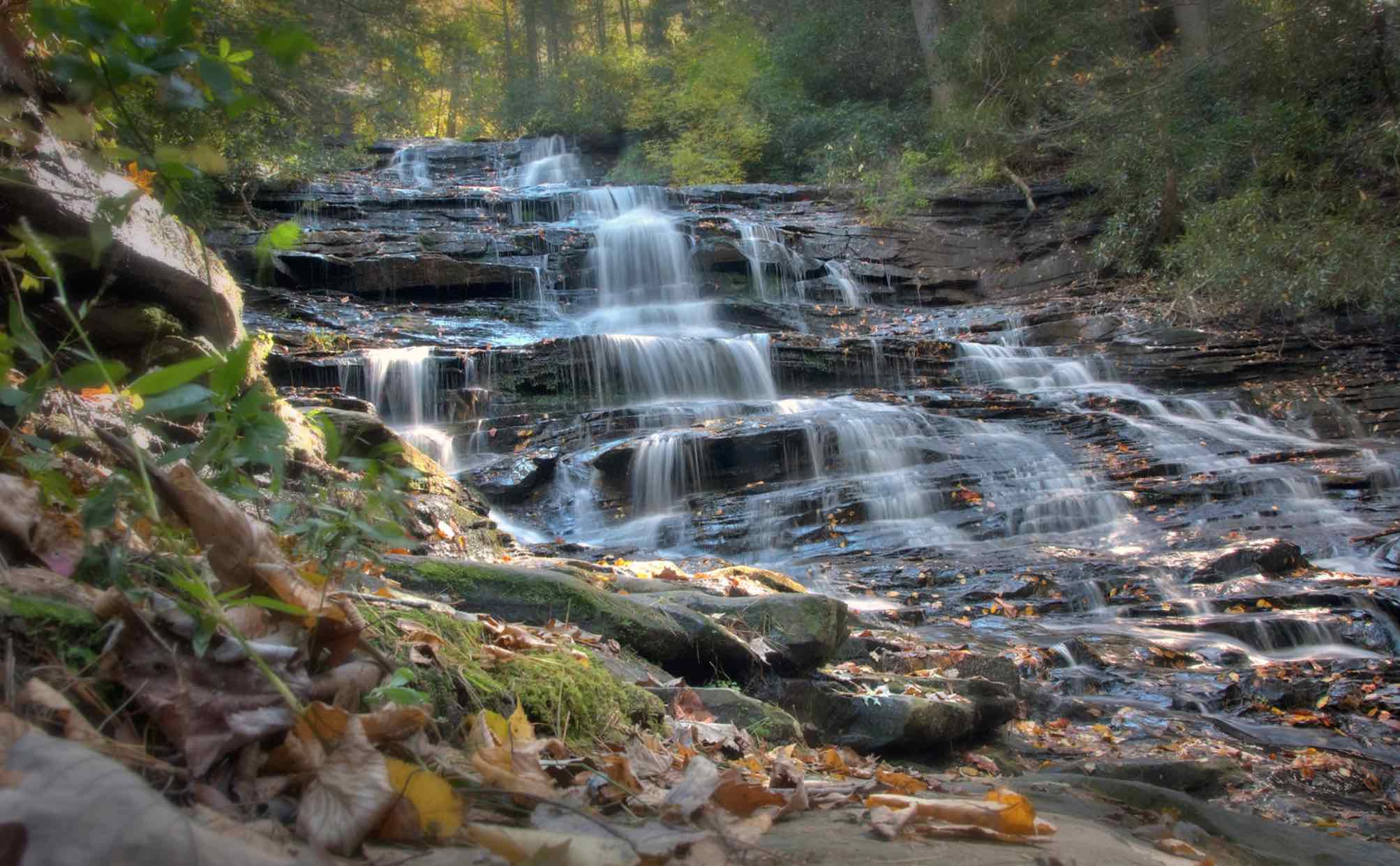

Minnehaha Falls, Georgia, USA.